Frozen moss buried in Antarctica for more than 1,500 years starting to grow again in laboratory

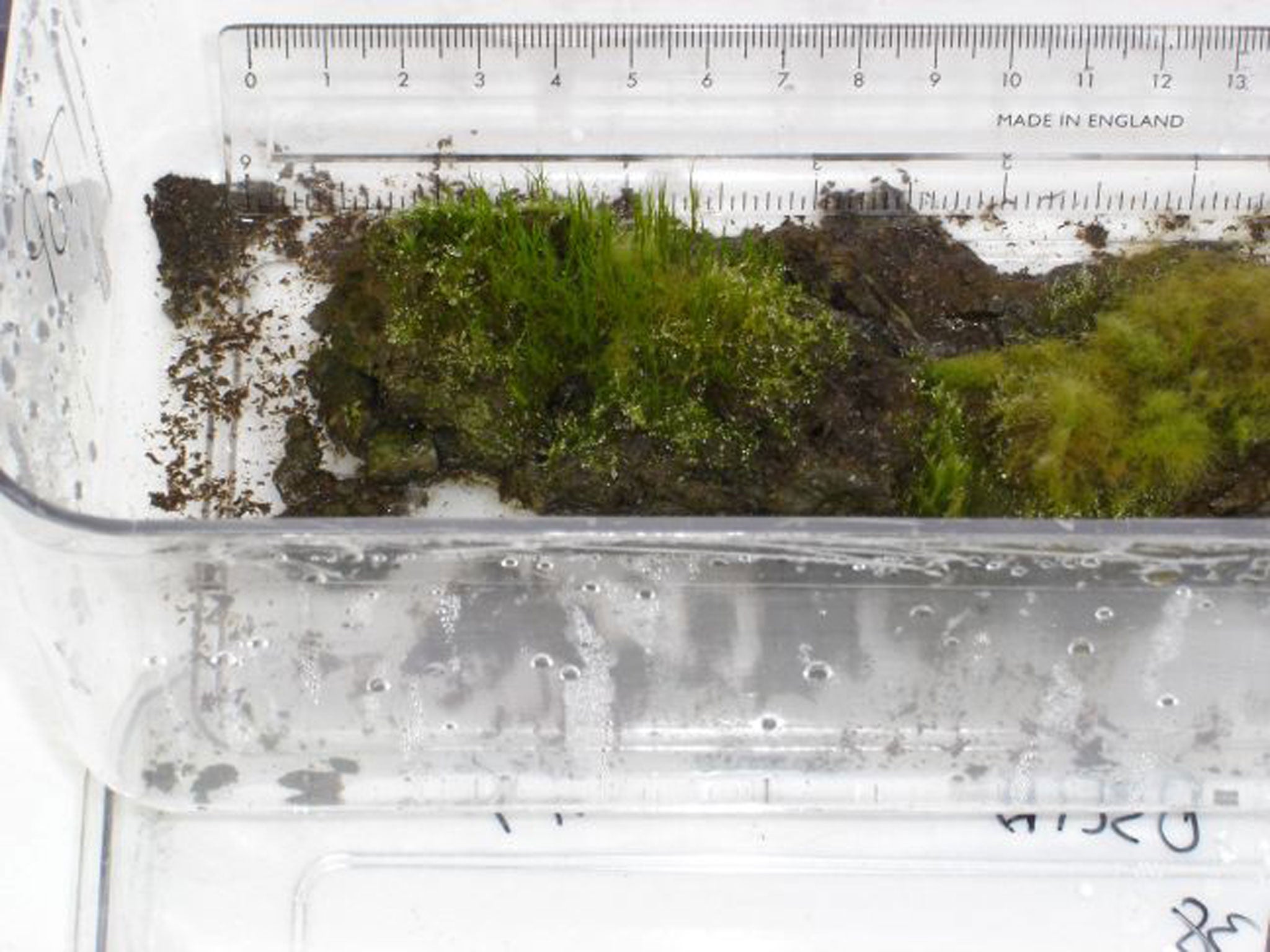

Frozen moss that had been buried in the Antarctic permafrost for more than 1,500 years and showed no sign of life has started to grow again in a laboratory, scientists said.

The moss last grew before the demise of the Roman Empire but its long period of being frozen solid in the ground did not appear to affect its ability to regenerate itself once it was defrosted, the researchers found.

It is the longest period of time that frozen plants have been able to survive. Previously, moss was known to survive being frozen for about 20 years – surviving for a millennium or more suggests the plants may be able to survive an ice age, scientists said.

Samples of the plant were recovered from Signy Island in Antarctica by drilling into a frozen bank of moss that scientists estimated to be at least 2,000 years old. Carbon dating suggested the samples were at least 1,530 years old.

When the moss samples were carefully thawed out in the laboratory, the plants began to grow again from their existing shoots or rhizoids, said Peter Convey of the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge.

“These mosses were basically in a very long-term deep freeze. This timescale of survival and recovery is much, much longer than anything reported for them before,” Dr Convey said

“This experiment shows that multi-cellular organisms, plants in this case, can survive over far longer timescales than previously thought. These mosses, a key part of the ecosystem, could survive century to millennial periods of ice advance, such as the Little Ice Age in Europe,” he said.

“If they can survive in this way, then re-colonisation following an ice age, once the ice retreats, would be a lot easier than migrating trans-oceanic distances from warmer regions. It also maintains diversity in an area that would otherwise be wiped clean of life by the ice advance.

“Although it would be a big jump from the current finding, this does raise the possibility of complex life forms surviving even longer periods once encased in permafrost or ice,” Dr Convey added.

The research is published in the journal Current Biology.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks