Climate crisis could cause global financial crash as economic models fail to capture risk

Researchers say governments and financial institutions underestimating threat because they rely on models that assume climate crisis impacts will be gradual

The climate crisis could trigger a global financial crash as temperatures rise beyond 2C, but governments and investors are relying on economic models that fail to account for the scale and severity of the damage, new research warns.

Researchers warn that governments and financial institutions are underestimating the threat because they rely on models that assume the impacts of the climate crisis will be gradual.

The analysis finds that as global heating increases, climate damage is more likely to arrive through extreme weather, cascading disruptions and tipping points, rather than through slow, manageable changes to economic growth. These risks, the researchers say, are largely missing from the tools used to guide public policy and investment decisions.

The research, led by the University of Exeter in partnership with think tank Carbon Tracker, draws on expert judgement from more than 60 climate scientists in 12 countries. It concludes that beyond 2C of warming, climate damage is likely to become structural and compounding, disrupting multiple sectors at once and threatening the conditions needed for economic growth.

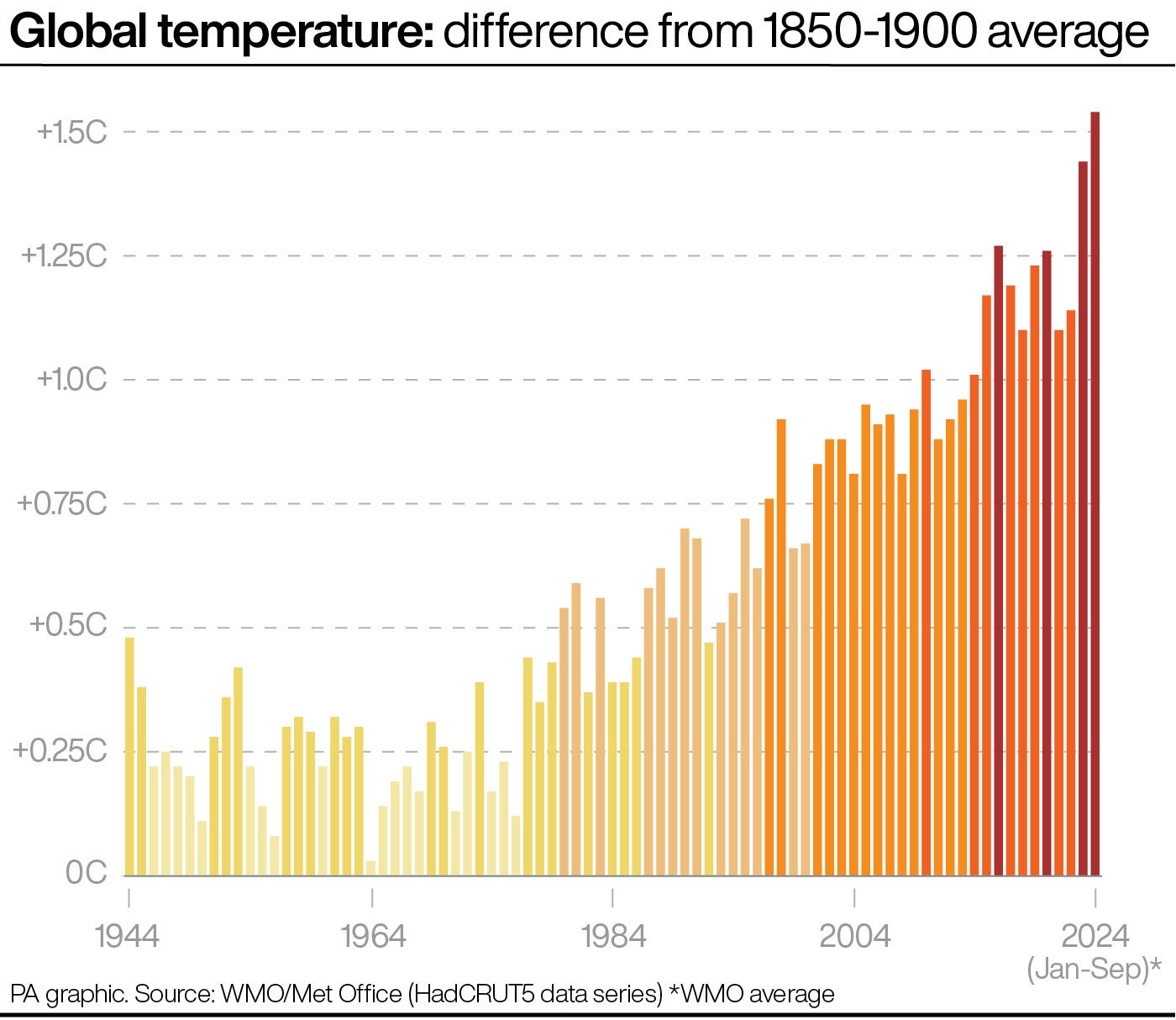

The 2C threshold from the Paris Agreement refers to a rise of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, a level scientists warn will sharply increase the risk of extreme weather, irreversible ecosystem damage and economic disruption.

“Beyond 2C, we’re not dealing with manageable economic adjustments,” said Jesse Abrams, the report’s lead author and a senior impact fellow at the University of Exeter.

“The climate scientists we surveyed were unambiguous: current economic models systematically underestimate climate damages because they can’t capture what matters most – the cascading failures, threshold effects, and compounding shocks that define climate risk in a warmer world.”

Most economic modelling links climate damage to changes in global average temperatures. The researchers argue this misses how climate change is actually experienced, through local and regional extremes such as heatwaves, floods and droughts, which drive the bulk of economic and financial disruption.

The report also warns that commonly used measures like gross domestic product can mask the true cost of climate damage. GDP can rise after disasters because of reconstruction spending, even as deaths, ill health, inequality, ecosystem loss, and social disruption increase. This can leave policymakers and investors with a false sense of resilience.

As temperatures rise, uncertainty also increases sharply, the researchers say. While models continue to produce precise-looking estimates, tipping points and extreme risks become more likely, undermining the assumption of steady growth that underpins many economic forecasts.

“For financial institutions and policymakers relying on these models, this isn’t a technical problem – it’s a fundamental misreading of the risks we face,” Abrams said, adding that current models assume “the future will behave like the past, even as we push the climate system into uncharted territory”.

The findings add to growing criticism of climate-economy models, which have previously been challenged by actuaries and scientists for understating the scale of potential damage in a hotter world.

Mark Campanale, founder and chief executive of Carbon Tracker, said flawed modelling had encouraged complacency.

“The net result of flawed economic advice is widespread complacency amongst investors and policy makers,” he said. “Until the gap between scientists and economists’ expectations of future climate damages is closed, financial institutions will continue to chronically under-price climate risks.”

Rather than aiming for precise forecasts, the report urges regulators and central banks to focus on protecting the financial system from destabilising outcomes. It calls for greater emphasis on extreme scenarios, compounding risks and systemic vulnerability.

For long-term investors, the report challenges the idea that climate risk can be managed through diversification alone, warning that portfolios can appear stable on paper while exposure to physical disruption continues to rise.

Laurie Laybourn, executive director of the Strategic Climate Risks Initiative and a board member at Carbon Tracker, said government action had not kept pace with reality.

“We are currently living through a paradigm shift in the speed, scale, and severity of risks driven by the climate-nature crisis,” she said, warning that many regulations remain “dangerously out of touch with reality”.

The researchers conclude that governments should not wait for perfect models before acting, warning that delay risks locking in decisions based on assumptions that no longer hold as the world moves closer to higher levels of warming.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks