Cop26: Can India wean itself off coal to deliver on climate goals?

Narendra Modi wants his nation to be a global leader on green energy, yet it gets 70% of its energy from coal and is still building more coal-fired power plants. Stuti Mishra explores why the country is still so dependent on the dirty fossil fuel

As the leaders of 197 countries gather for the UN’s global Cop26 summit to discuss their efforts to combat climate change, including international pressure to phase out fossil fuels, an ongoing energy crisis has left India scrambling to acquire more coal.

Power cuts and warnings of extended blackouts as a result of the potential coal shortage in Asia’s second-fastest-growing economy has been yet another reminder of how heavily India relies on coal for its electricity generation even after making progress in renewable energy.

More than two-thirds of India’s electricity is still generated by coal-fired thermal power plants. And it is the second-largest producer and consumer of coal after neighbouring China.

The burning of coal to generate electricity is responsible for 40 per cent of all global carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels, and mining it comes with a host of environmental hazards. Experts are clear that if global warming is to be kept below 2C – the target of the Paris Agreement – the use of fossil fuels needs to be dramatically scaled down.

At Cop26, there will be a push for large economies like India’s to commit to more ambitious climate goals and it has been confirmed that India’s prime minister Narendra Modi will be attending the summit, boosting hopes that India will use the platform to announce actions.

According to its 2015 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) under the Paris Agreement, India has set a target of reducing emissions intensity relative to GDP by 33 to 35 per cent by 2030, to achieve about 40 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources and enhance its carbon sink by planting trees.

While India has been able to create the world’s fourth-largest renewable energy structure, this does not automatically mean the country will be ceasing coal combustion anytime soon. Phasing out coal – India’s cheapest source of electricity – will have major implications for the country’s economy.

The partly government-owned Coal India Limited provides about 85 per cent of India’s domestic production of coal and is the world’s largest coal mining company, contributing revenues to the government and support to millions of people who depend on the sector for jobs and pensions.

“Coal is deeply entrenched into the national economy [of India] and more so when we look sub-nationally with the mining and utilisation lens,” Dr Rahul Tongia, a senior fellow at the Delhi-based think tank Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP), tells The Independent.

The government recently announced India would reach the target of 175 gigawatts (GW) renewable energy generation by 2022, sounding hopeful of meeting the 2030 target of achieving 450 GW of renewable energy installed capacity including nuclear and large hydropower by 2030.

But according to World Resources Institute (WRI) India’s climate programme director Ulka Kelkar, the 450GW target “is not an easy one” for India.

“It requires India to triple its renewable energy capacity in less than a decade,” she says. “Even though renewable energy has become cost-competitive compared with coal, this 450 GW target will require substantial investments, land, and the right pricing and financial incentives.

“India could consider including this domestic target in its next NDC under the Paris Agreement,” she adds.

Currently, India’s installed non-fossil fuel capacity is 39 per cent, close to its NDC target of 40 per cent, with the rest still coming from fossil fuels. But installed capacity refers to the maximum generation the given infrastructure is capable of, rather than actual power produced. Since generation from renewables like wind, hydro and solar varies depending upon the speed of the wind or visibility of the sun, the output remains erratic.

Dr Tongia says India should adopt a “holistic approach” for a smooth and timely transition. “Pushing off structural changes as well as avoiding transparent accounting until later on will only make the problem that much harder in the future,” he adds.

While coal is currently the cheapest energy source, the cost of renewables and battery solutions is steadily reducing – meaning that even from a business perspective, reducing the amount of coal in India’s energy basket makes sense.

“Not only are renewables becoming cost-competitive compared with coal, it is also getting a policy push due to India’s renewable energy targets,” Ms Kelkar says.

“Some Indian states like Gujarat, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and Karnataka have announced that they will not build new coal power plants, as have major public and private electricity companies including India’s largest power utility National Thermal Power Corporation (NTPC),” she adds.

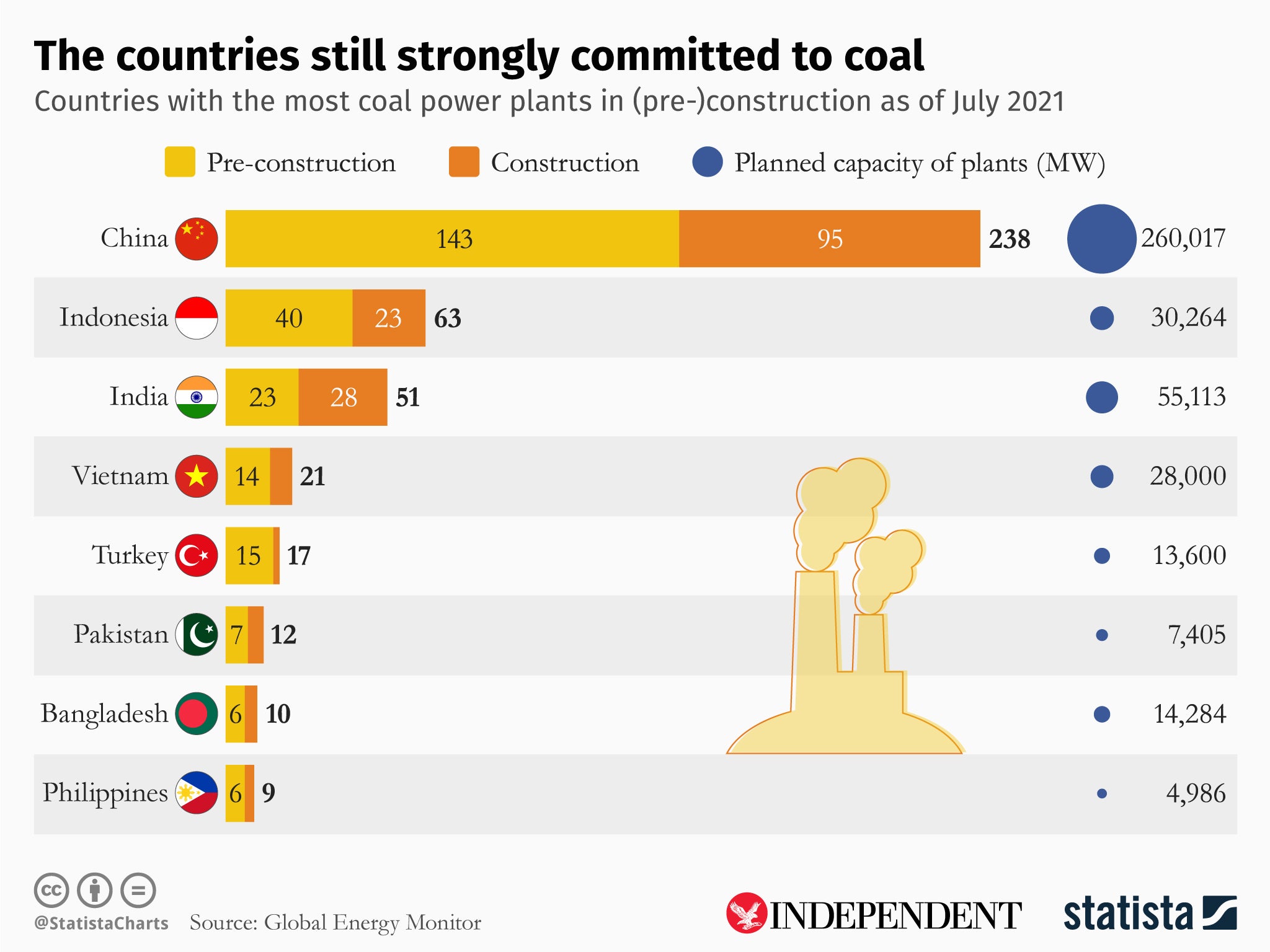

Such a transition cannot happen overnight; there are still coal power plants being built there today. Despite the push for renewables, India is one of three countries with the largest number of planned coal power plants in the world, after China and Indonesia.

India has the world’s fifth-largest proven coal reserves – enough to last it for more than a century. And despite Mr Modi’s expressed goal of establishing the country as a global leader in green energy, the fact is that India’s energy needs are growing at a rapid rate.

India is already the third-largest carbon emitter in the world, contributing 7 per cent of global emissions in 2019, after China and the US which are responsible for 27 per cent and 14 per cent respectively. Unlike those countries, it hasn’t committed to a target year for achieving carbon neutrality.

India is expected to take over China as the world’s most populous country by 2027, and up until now making electricity widely available to its massive population has been a key policy goal for the government. A village in remote Manipur officially became the last in the country to be linked up to the national grid only in 2018 – though coverage remains patchy.

India’s per capita electricity consumption is just a third of the global average; bringing power to more people will be an inevitable factor in developing the country. So despite international pressure to keep it in the ground, even if the proportional share of renewables increases in India in the coming years, experts believe the total amount of coal burned will not see a peak anytime soon in the nation.

This is a very significant decade for India’s energy transition because the country is planning to meet almost all its new and unmet energy needs from clean energy sources. The country is also aiming to leapfrog to green hydrogen - a clean fuel that will be key to industrial decarbonisation.

“The growth rate of electricity from coal has certainly come down, but it’s premature to consider a peaking of coal-fired power. Coal dominates electricity production today,” Dr Tongia notes. “Even under scenarios of very high renewable energy penetration by 2030, India may just about reach the plateau of its coal generation around then.”

The patchy nature of some renewables means that a lot of developed nations are utilising other non-coal fossil fuels like natural gas to help smooth their energy transitions. But “the UK and US reduced their coal consumption not predominantly because of the rise of renewable energy but because they had access to a cheap source of natural gas, which India lacks,” Dr Tongia says.

He suggests a more realistic goal for India might be to reduce emissions by improving the efficiency of its coal-fired power systems instead of getting rid of the resource completely. Dr Tongia says in a few years, India will have “to figure out whether it requires new coal capacity beyond the few tens of gigawatts under construction already”.

Dr Tongia adds that the rising demand for cooling as a result of the warming climate will also “drive the need for not just new electricity per se, but electricity at the right time in a firm or dispatchable manner”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks