Predators that ‘nibble their prey to death’ form new branch of evolutionary tree of life

‘Lions of the microbial world’ are rare, but important part of ecosystem

There’s a whole new branch on the evolutionary tree of life, made up entirely of predators who “nibble their prey to death”.

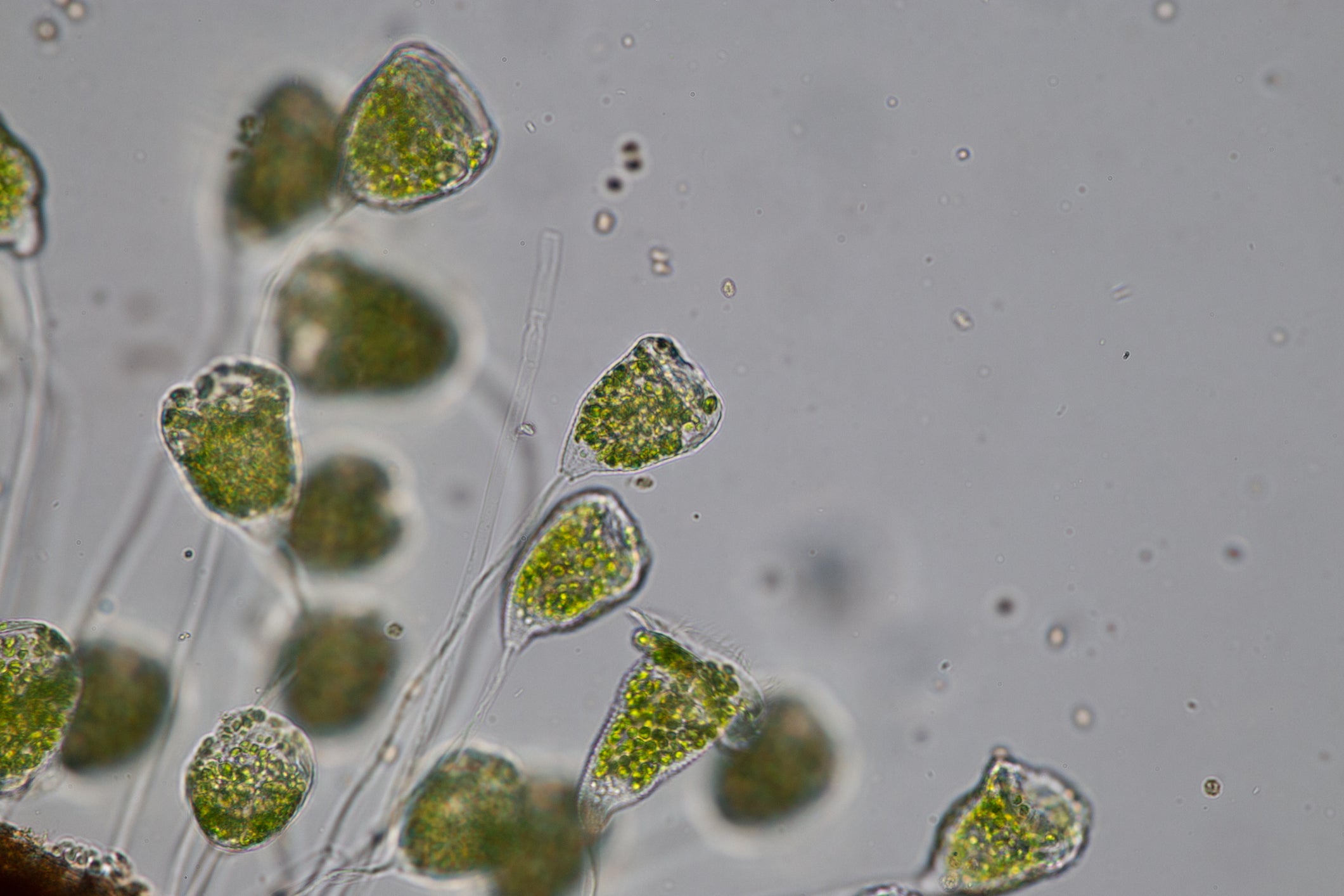

These are not the fearsome species we normally associate with predation, but form an extensive group of microbes which use “tooth-like structures” to nibble chunks off their prey – hence the group’s name – the “nibblerids”.

They form a distinct evolutionary group, separate to their relatives the “nebulids”, which consume their prey whole.

The two groups are now recognised as comprising an ancient branch on the evolutionary tree of life, to be known as “provora”.

Despite the obvious differences between familiar predators such as lions and tigers, and these microscopic life forms, there are also a host of similarities too, the research team from the University of British Columbia (UBC) said.

Like lions and tigers, these microbes are numerically rare but play an essential role in the ecosystem, said the study’s senior author Dr Patrick Keeling, professor in the UBC department of botany.

“Imagine if you were an alien and sampled the Serengeti. You would get a lot of plants and maybe a gazelle, but no lions. But lions do matter, even if they are rare.

“These are lions of the microbial world.”

These predatory microbes were first discovered in seawater samples taken from marine habitats around the world, including the coral reefs of Curacao, sediment from the Black and Red seas, and water from the northeast Pacific and Arctic oceans.

“I noticed that in some water samples there were tiny organisms with two flagella, or tails, that convulsively spun in place or swam very quickly,” said first author Dr Denis Tikhonenkov, a senior researcher at the Institute for Biology of Inland Waters of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

“Thus began my hunt for these microbes.”

Dr Tikhonenkov, noticed that in samples where these microbes were present, almost all others disappeared after one to two days.

They were being eaten.

Dr Tikhonenkov “fed the voracious predators with pre-grown peaceful protozoa”, the team said, allowing him to cultivate a population of the organisms in order to study their DNA.

When he examined them, he found huge genetic differences from other life forms.

“In the taxonomy of living organisms, we often use the gene [known as] ‘18S rRNA’ to describe genetic difference,” he said.

“For example, humans differ from guinea pigs in this gene by only six nucleotides. We were surprised to find that these predatory microbes differ by 170 to 180 nucleotides in the 18S rRNA gene from every other living thing on Earth.

“It became clear that we had discovered something completely new and amazing,” Dr Tikhonenkov said.

On the tree of life, the animal kingdom would be a twig growing from one of the boughs called “domains”, the highest category of life. But sitting under domains, and above kingdoms, are branches of creatures that biologists have taken to calling “super groups”. About five to seven have been found, with the most recent in 2018 – until now.

Understanding more about these potentially undiscovered branches of life helps us understand the foundations of the living world and just how evolution works.

“Ignoring microbial ecosystems, like we often do, is like having a house that needs repair and just redecorating the kitchen, but ignoring the roof or the foundations,” said Dr Keeling.

“This is an ancient branch of the tree of life that is roughly as diverse as the animal and fungi kingdoms combined, and no one knew it was there.”

The researchers plan to sequence whole genomes of the organisms, as well as build 3D reconstructions of the cells, in order to learn about their molecular organization, structure and eating habits.

The research is published in the journal Nature.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks