Wake-up-calls and printing press blockades: Climate activism in the age of coronavirus

With the climate crisis not going anywhere, activists felt there was no option but to continue protesting amid the pandemic. Emma Snaith speaks to some of those involved

It was a school night in September when 17-year-old student Abby DiNardo stood with dozens of masked teenagers outside Republican Senator Pat Toomey’s house demanding that he “wake up”.

Holding candles and banners in the Sunrise Movement’s signature yellow and black colours, the climate activists called on the Pennsylvania senator to pay attention to the climate emergency and listen to their demands.

It had been four days since the death of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. The Sunrise activists feared that Senator Toomey, a Wall Street banker who has repeatedly voted against climate action measures, would vote to confirm a new justice who would undermine the fight against the climate crisis.

“Climate change isn't going to stop just because it's a school night,” Abby, who coordinated the action, says. “We wanted Pat Toomey to keep our future in mind because we're not fighting for his future anymore, his future is the present.”

Like climate activists around the world, members of the Sunrise Movement felt that there was no choice but to continue protesting amid the pandemic during such a crucial year in the fight against the climate crisis.

Not only could the outcome of the US election shape the course of global climate action for years to come, the UN has predicted that we only have 10 years left to avoid climate catastrophe.

Read more: The biggest climate crisis moments of 2020

But how effective could climate protests be in the face of stringent social distancing measures and other Covid rules? Could the revolution be livestreamed?

2020 US election

In the run-up to the US election, the Sunrise Movement said it reached 3.5 million young voters in swing states through socially distanced means including phone-banking, social media and friend-to-friend organising. It is no mean feat for a movement founded only three years ago by a group of disparate young activists to help elect supporters of clean energy in the 2018 midterms.

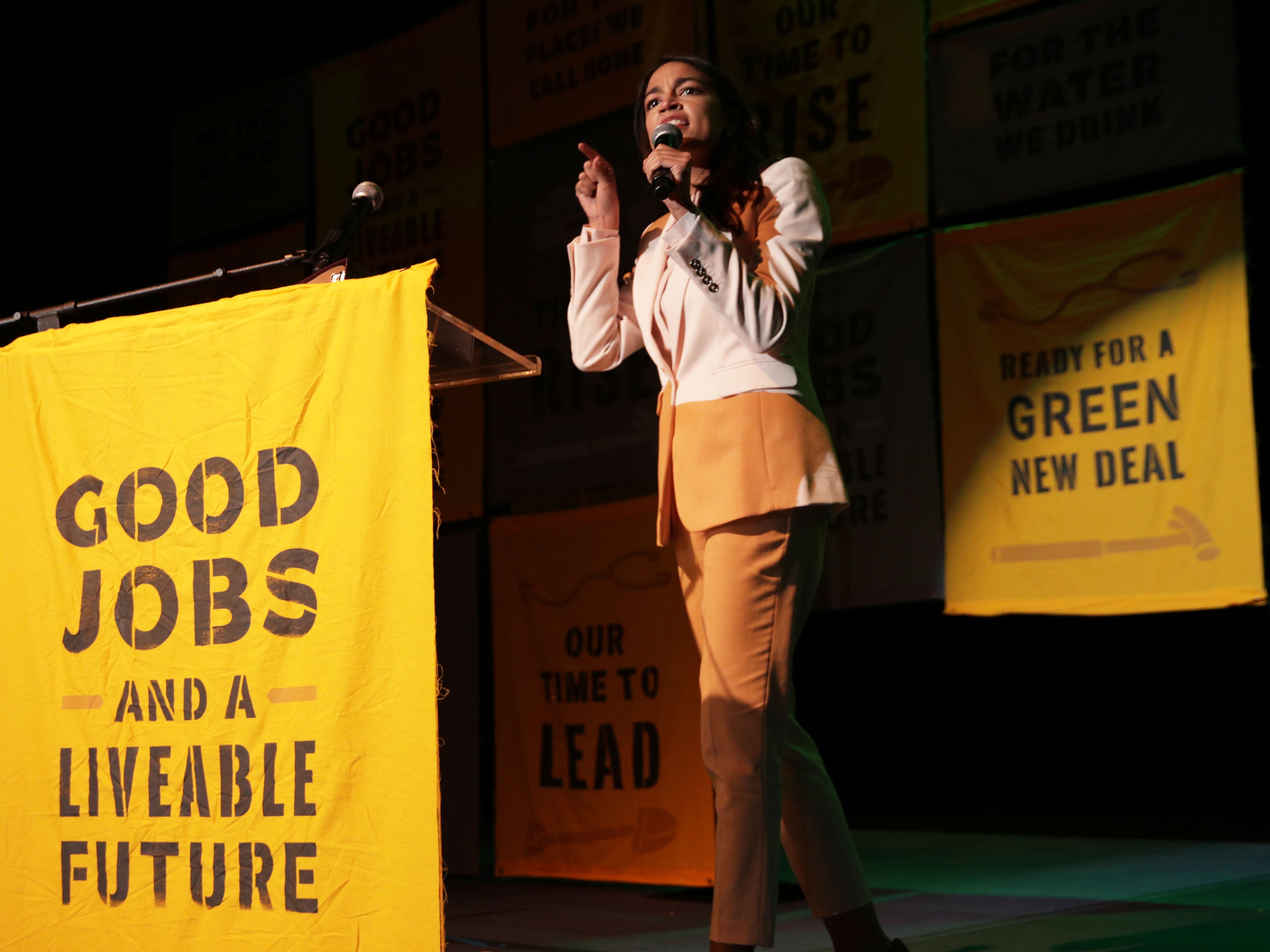

Closely allied with congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, the youth-led Sunrise Movement is now pushing Democratic leaders to embrace the Green New Deal.

And now Joe Biden has won the election, they plan to hold him to account over the most ambitious climate agenda ever adopted by a US president.

“Without the youth climate voting bloc, he wouldn't be in office right now,” Abby says. “We’re now focussing on pushing him more left and getting the first pillars of a Green New Deal by six months into his term.”

Global climate strikes

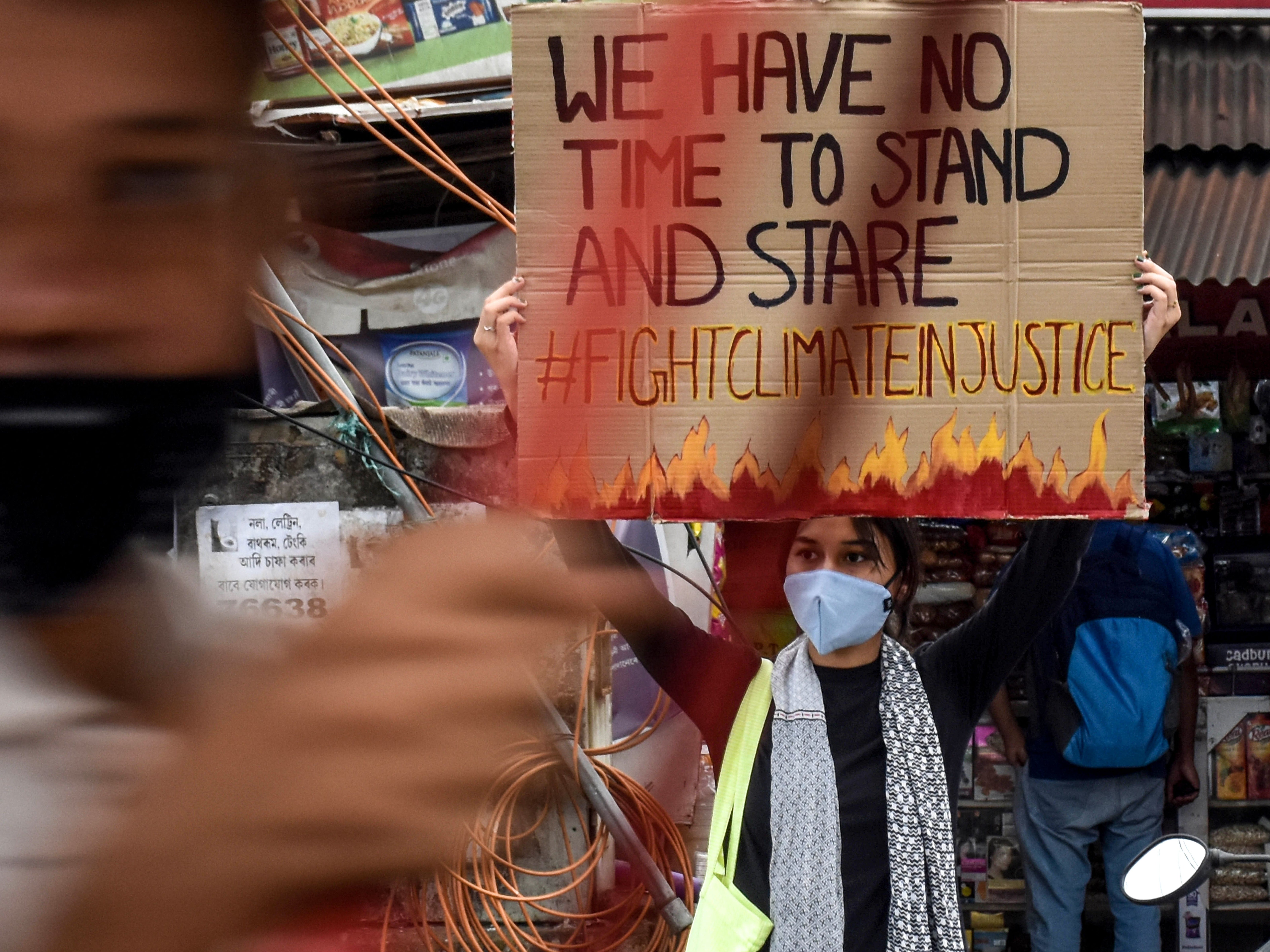

Meanwhile in Delhi, Fridays for Future activists were also calling for their leaders to “wake up” to the reality of the climate crisis. They staged a socially distanced protest in September as part of a week of global climate strikes led by Greta Thunberg.

Dozens of masked protesters sat on the street, two metres apart, outside the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Watched on by police, they drew messages with chalk on the street urging leaders to “wake up” and held signs with slogans like “it’s getting hot in here”. Some studies suggest India could see more than a million deaths a year from extreme heat by next century.

Laksh Sharma, a 20-year-old organiser from Fridays for Future Delhi, highlights a brutal 2016 heatwave which saw scores of people from the most marginalised communities in the city being hospitalised. “This is how climate change is already affecting us,” he says.

He adds that many protesters were also motivated to join the climate strikes due to a problem intimately connected to the climate crisis – air pollution. “Last winter we could actually feel our eyes burning, our lungs hurting,” Laksh says.

He describes how the lockdown in the city earlier in the year had offered a brief reprieve from the pollution, as many reported around the world – “everything was clearer, birds were chirping”. But now Laksh says air pollution in the city has returned to levels similar to that seen before lockdown.

Yet Delhi, like many other parts of the world, saw far more subdued climate strikes compared to last year, when 6 million people globally were estimated to have taken part in the global day of action..

Greta Thunberg’s strike in Sweden was limited to 50 people by the country’s lockdown laws and other strikers forgoed in-person protests to take part in a 24-hour-zoom call. “So we adapt,” Thunberg said at the time.

Printing press blockades

The pandemic also dampened Extinction Rebellion (XR)’s protests this year, with the group deciding to cancel its scheduled “April Rebellion”.

The group originally planned to take to the streets of London, following on from the previous rebellions in April and October 2019 which saw thousands of protesters bring parts of the capital to a standstill for days.

Instead, XR organised smaller actions targeted at what they say are some of the key actors driving the climate crisis, from the media to thinktanks and fossil fuel companies.

“There was a natural move to do more targeted actions that show the complexity of the problems that we are dealing with here,” XR organiser Clare Farrell says.

XR’s most high-profile protest of the year saw activists block the roads outside the printing presses of a raft of newspapers – including The Sun, The Times, The Daily Telegraph and The Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday.

The action was staged to highlight the failure of the media to “report on the climate and ecological emergency”. On 5 September, protesters blocked roads with vehicles and bamboo structures outside the printing sites in Broxbourne, Knowsley and Motherwell. Banners draped over vans read “Free The Truth” and “5 Crooks Control Our News”.

The action, which delayed the distribution of newspapers over the weekend, drew a lot of media coverage – and strong criticism from politicians, with prime minister Boris Johnson condemning the protests as “completely unacceptable”, and home secretary Priti Patel describing them as “an attack on our free press, society and democracy”, branding the group “criminals”.

But XR and other environmental activists believed the protests were necessary. Steve Tooze, a former journalist and one of the XR activists arrested at the action, says the action was needed to “open the conversation” about media ownership and the climate crisis.

“I was a journalist for more than 20 years, and worked for Murdoch newspapers, including The Sun, The News of the World, and The Times, and for The Daily Mail,” he says.

“I saw those organisations from the inside. The crooks who own our media have pursued a free-market extreme right wing agenda for 30 years, and have been involved in a campaign of climate denial propaganda.”

Steve adds: “If we don't get the print media to treat this [the climate crisis] like the emergency it is, my children may not have a future.”

While XR has had to adjust its tactics during the pandemic, the group is still thinking big. Organiser Clare Farrell said the group plans to hold mass civil disobedience protests again when Covid restrictions lift, alongside more targeted actions.

Where racial justice meets climate activism

The lockdown lull has also given XR a chance to reflect on the way it aligns its climate fights with racial justice. Critics of XR have said that its focus on peaceful arrests as a non-violent tactic displays an insensitivity to the reality of police racism, and discourages black and ethnic minority people from joining the group.

But during the quieter periods of 2020, XR began to focus more on becoming a “movement of movements” and recognising the intersection of racial justice and climate activism.

From its inception, the group says it has worked with Stop the Maangamizi, who campaign for pan-African reparations. But this year XR strengthened these ties and helped support a protest in September which saw demonstrators temporarily block Brixton Road in London.

In the wake of the police killing of George Floyd in the US May, the Sunrise Movement also made greater efforts to oppose racism and police brutality. Members were encouraged to attend and act as marshalls at Black Lives Matter protests, as well as to speak out about racial justice.

Sunrise also started providing stipends for people of colour or those on low incomes to join its Down Ballot Disruption Project. The programme, held entirely over Zoom, aims to teach young people how to canvass for progressive candidates in their local elections.

“We didn’t want to become this white-washed campaign team,” Sunrise activist Abby DiNardo says. “Being a campaign volunteer can be so inaccessible because you don't get paid.”

Meanwhile, Fridays for Future India used the quieter lockdown period to move away from the “Eurocentric ideals of climate activism” and learn from other activists on the ground.

“When we first started, most of our members were privileged and lived in urban areas, so had access to education on the internet and could learn about Greta Thunberg,” 20-year-old organiser Sriranjini Raman says. ”Now we're going to find our own way.”

As tens of thousands of farmers began protesting at the Delhi border over new agriculture laws which they say will destroy livelihoods, Fridays for Future India showed their solidarity with the movement. They joined other environmental groups under the banner “Greens with Farmers”.

The group also realised the need to centre the voice of indigenous communities in their movement. “Indigenous people are the original stewards of the land and they have been protecting forests and biodiversity for centuries, Sriranjini says. “So we should be listening to them and following their lead.”

During lockdown, Laxmi G Murmu started the first Fridays For Future chapter for indigenous youth in Asia in the eastern state of Jharkhand. She stresses the importance of “taking care of nature without discrimination” and asks: “What is the point of having a good economy when there are no people left to benefit from it?”

Online activism and Mock Cop26

With lockdowns thwarting many plans for mass protests, climate activists learned to collaborate in completely new ways online.

Climate strikers moved their weekly Friday protests onto mass zoom calls and organised Twitter storms to pressure selected officials to take action on the climate crisis. In April, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day was celebrated with a 72-hour livestream.

But perhaps most notably, young activists frustrated by the postponement of this year’s annual UN climate summit decided to host their own version – Mock Cop26. The two-week conference designed to mirror the UN talks took place entirely online and involved young people from more than 140 nations as negotiators.

Josh Tregale, an 18-year-old from the UK who deferred his university place to take part, said he hoped the event could be a model for what was possible with online negotiations. “It feels counterproductive to fly thousands of people around the world for a conference about reducing carbon emissions,” he says.

Josh added that the event also showed how Cop26 could better prioritise the voices of the global south. During Mock Cop26, these countries were allowed five delegates each, as opposed to three per country in the global north. And the event was pushed back to later in November to avoid clashing with Diwali.

“Hearing more from those on the front lines of the climate crisis really put into context the impact this has on people’s lives,” Josh says. “It makes it harder for people not to want to act.”

Pallawish Kumar, one the delegates for Fiji at the conference, said 11 islands in the archipelago face going underwater over the next decade due to sea level rises.

“We are already suffering a lot because of climate change,” he says. “More than 18 communites have now been relocated in Fiji and now many more face this too.”

Pallawish, who is also involved in several climate projects in Fiji, said that when farming communities in coastal areas are forced to relocate, they lose all their land and find themselves without a livelihood.

And yet he points out that while Fiji accounts for less than 1 per cent of global carbon emissions, it has already committed to reducing its emissions to net zero by 2050 – unlike many countries in the global north.

“Because of the irresponsible actions of developed countries, places like Fiji are facing the consequences,” he says. “When I grow old I want my children and descendents to be able to enjoy the beauties of nature as I did.”

At the end of Mock Cop26, delegates presented their formal treaty to Nigel Topping, the UK’s high level climate action champion. They called on world leaders to prioritise the policies during next year’s Cop26, from introducing climate education at every level to tougher ecocide laws and a commitment to keeping the global temperature rise to to below 1.5C above pre-industrial levels.

“I think if there's willpower it [the treaty] is realistic,” Josh says. “Lots of people say governments can't do anything quickly. But this year has shown that they really can.”

Across the climate activist movement there has been a niggling sense of urgency to keep up the momentum of the successful wave of global protests in 2019.

Indeed, levels of CO2 in the atmosphere have continued to rise this year despite a temporary dent to emissions as a result of country-wide lockdowns.

Mass climate protests of the scale of last year may have been paused for now, but there’s still huge appetite for their return from groups like XR, Fridays for Future and the Sunrise Movement.

“People [in XR] have worked so hard to make sure that we don't miss the year”, Clare Farrell of XR says.

“The virus hasn't changed anything about the Arctic, rising carbon emissions and methane release. Physics doesn’t care about Covid affecting us.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks