Are virtual power plants really the answer to the energy crisis?

Virtual power plants are the talk of the town: provide extra electricity by merging multiple energy resources into one. Et voila! But even this might be too blunt a tool for our future needs

The fleet of small-scale solar systems, batteries and flexible loads in our electricity system will grow rapidly in coming years. But how to coordinate them efficiently in our complex electricity grid, and how to make sure their owners get a fair return?

Virtual Power Plants (VPPs) are the talk of the town right now. But they may turn out to be like using a sledgehammer on a walnut. More nuanced systems are being developed to integrate large numbers of small scale solar systems and batteries into the grid. If successful, they will be able to apply market principles to deploy and reward these so-called distributed energy resources.

The concept of a VPP is fantastic – take a whole host of small, individual, controllable, distributed energy resources such as battery systems, hot water systems, electric vehicle chargers, air conditioners and pool pumps, and aggregate them into something far larger and more useful.

Taken together, they can indeed be operated like a modestly sized power station. If you need a little more power output from your virtual power plant, simply wind back Mr and Mrs Jones’s air conditioner a little, turn down Joe Bloggs’s pool pump and increase the output from the Nguyen family’s battery. Voilà!

But there are several problems with this. What if Joe Bloggs is connected a long way from where the extra power is needed, making his pool pump the least efficient resource to use on this occasion? Or what if the electricity network in the Nguyens’ area is already close to its technical limit? Or what if the Joneses are throwing a party today and don’t want to skimp on air conditioning?

A simple VPP, which lumps all of these resources together as a single entity, can’t typically use them optimally. It doesn’t account for real-time network losses, won’t consider network technical constraints like current and voltage limits, cannot account for individual households’ specific energy needs and doesn’t allow for time- and location-specific responses to price signals. It generally doesn’t deal well with issues of equity between consumers, and may require private information about consumers’ energy behaviour.

A more delicate tool

This is where we need to look past the simple VPP model, to a more comprehensive approach – a “VPP 2.0”, if you will. There are options on the table already, some being developed in Australia. They could make it possible to run the power system with a very large number of distributed energy resources.

One example is the CONSORT trial project being run on Tasmania’s Bruny Island, which links up 33 homes with battery storage into a single network, orchestrating their operation via “network aware coordination” algorithms. This system takes account of variations in price signals, both in location and time, and then manages the batteries’ outputs accordingly.

A household’s battery with an abundance of stored energy may, for example, be co-opted to solve a particular issue in the section of network to which it is connected. However, a different household on the same piece of network may foresee a later use for its stored energy which will be of higher value, and so it should not respond to the same price signal. Yet another household may be connected at a location where it has little or no influence on solving the local issue, and thus should not be used at all if the problem can be solved more cheaply and effectively elsewhere.

This leads to the idea that a market-based approach may be the best way to marshal all of these distributed energy resources. After all, what we are trying to do here is match up supply and demand in the most efficient way – precisely what a market does best.

The goods in this market are supplied by the various distributed energy resources. The buyers in the market might include energy retailers, electricity network operators, power system operators, wind and solar farm operators, and large or small energy customers.

Operating and clearing a distributed energy market is more challenging than for a conventional market, not least because of the physical limitations imposed by the electricity grid itself. But it may be worth it: a market’s potential to find the genuine value of DER services, to allow a degree of agency for market players, and to produce the most efficient outcome for the electricity system as a whole could make for a compelling case.

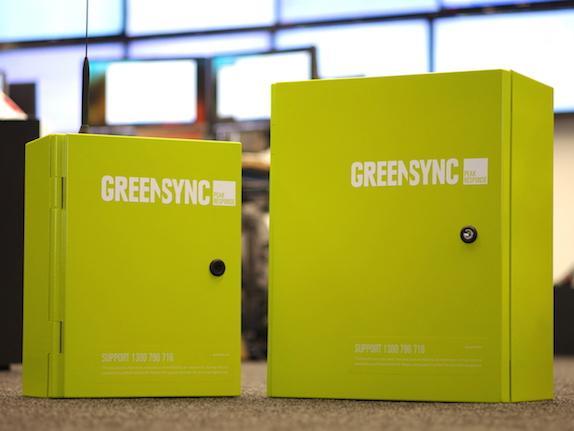

This is a view certainly shared by the proponents of the ARENA-funded deX project (decentralised energy exchange), led by Melbourne’s GreenSync, which aims to demonstrate a working digital marketplace for this kind of distributed electricity services.

Of course, a market won’t just develop on its own. Distributed resources need to be deployed in sufficient volume and in such a way that they can communicate with a market exchange platform, can automatically make feasible offers, and then execute them when those offers are accepted.

At the moment there aren’t many distributed resources deployed. But market development could be fostered, for example, by operating in its early phase as a market for longer-term contracts (three years, for example) rather than for near- or real-time services, thus providing up-front incentives for suppliers to install distributed energy resources where they are valued most highly.

The next 10 years

A decade from now, there will certainly be a large and growing fleet of flexible, distributed energy resources in our electricity system. The technological options are compelling, and Australian consumers and businesses have shown their appetite for them.

How they will be coordinated to equitably and efficiently meet the many and varied objectives of our energy system is unknown. An efficient market will need time to develop, not to mention plenty of participants. But it can be structured to make it attractive to join, which would speed up the process.

Now is the time to do the analysis, to develop and test different approaches, and to make informed decisions about a consistent and inclusive approach that is attractive to households and businesses alike.

Evan Franklin is a senior lecturer in engineering at the University of Tasmania and Frank Jotzo is director of the Crawford school of public policy at the Australian National University. This article first appeared on The Conversation (theconversation.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks