What happens when seagulls attack? 'It's a war zone, we are even seeing people with mouth injuries'

We'd rather they were plucking pilchards from the sea and looking scenic on our postcards, but the fact is we’ve taught the gulls the very worst of human nature. David Barnett watches these giant birds who are quite literally taking the food from the mouths of babes

At the Porthminster Beach Cafe in St Ives on the Cornish coast, the staff issue a standard sign-off as they hand over your panini or prawn baguette, as second-nature to them as an American diner waitress exhorting a departing customer to have a nice day.

“Watch out for the gulls.”

Pity the unwary traveller who heads out of the shelter of the cafe canopy and on to the open beach without heeding this warning. It might seem just a short hundred yard walk in the glorious sunshine from cafe to the pop-up tent enclosed by windbreaks where you have made your camp, but the staff aren’t in any way exaggerating.

It’s a war zone out there, and your fingers, your arms, even your mouth are the collateral damage. Your lunch is the prize. And the gulls are the aggressors.

I know, for once I was that foolhardy holiday-maker, proudly brandishing my wares from the cafe at the distant specks of my family sitting by the shoreline. I had fulfilled the hunter-gatherer role. I was returning triumphant from the long queues. I had food!

Had being the operative word. Just like no one expects the Spanish Inquisition, nobody sees the gulls in the seconds before they strike. They are white streaks, feathered arrows, Exocet missiles locking their beady eyes on their target as sure and as true as any hi-tech guidance system. One second I was waving a baguette, the next my hand was empty and my lunch was on the sand, a yellow beak tearing into the paper bag, prawns flying around as several other gulls materialised out of nowhere to help the triumphant dive-bomber dispose of his booty. Oh, the humanity.

Once seagulled, twice shy. We have holidayed in St Ives every year since, and I have not again fallen victim to the gulls. But for every savvy survivor who returns, each summer brings a new intake of wanderers unschooled in the ways of the gulls, who have read the stories but think them exaggerated or one-offs. And every year I see, sometimes two or three times a day, what happens When Seagulls Attack.

“Seagull attacks are on the rise in Cornwall and people are getting injuries in their mouths” was the headline on a news story on the website of Cornish newspaper the West Briton last week. Well, ewww. But true. The gulls are literally taking the food from the mouths of babes. Claire Field, community pharmacist based at Carbis Bay, told the newspaper: "My colleagues at the Leddra pharmacy may see one or two people a week when the birds are nesting who have been hurt by an aggressive seagull.

“However, the reality is that there are probably more people who have been attacked by them but have decided to treat the wounds themselves rather than seek the advice of a pharmacist.

"We have even seen adults and young children with cuts around and inside their mouths as well as their hands where sneaky seagulls have swooped down to take their food.”

Sitting on the beach last week, I regularly heard the traditional cry of dismay from an astonished adult relieved of a bacon sandwich just feet from the cafe, the dumbfounded momentary silence filled by the wailing of a small child as an ice-cream was cruelly snatched from their little hands, the swooping of wings as other gulls joined the fray, the high-pitched cawing of one gull on the group.

All the time, there’s one gull making a hell of a racket when a successful sortie is carried out. Is it a triumphant bugle-call? An alert to other gulls wheeling overhead that there’s food on the go? The tribal chieftain making sure something is left for him?

“They are very raucous birds,” points out Tony Whitehead of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. “Sometimes you’ll get a young gull making a kind of mewling, begging noise, other times they can be quite noisy just to warn others of potential danger all around them.”

Such as, presumably, the presence of several people who’ve just had their pasties nicked.

It’s difficult not to imbue the gulls with some kind of malign intent and dark intelligence. They look organised. Perched on the banners flapping above the Porthminster cafe, the gulls are permanent lookouts, keeping their beady eyes peeled for people leaving the cafe queue laden with goods. Up above, air-support gulls ride the thermals in ever-decreasing spirals, ready to put their wings back and dive, dive, dive. There are even ground troops, gulls who stalk between the sunbathers, sometimes just standing there and staring at you, as though they can see straight into your very soul, or at least into the polystyrene box protecting your breakfast.

Which is all rubbish, of course. Whitehead points out that the gulls — the ones in St Ives are most likely herring gulls — are really just trying to rub along with us. “There’s a lot of hysteria sometimes,” he says, “especially a couple of years ago when there was an incident when a small dog was killed which co-incided with David Cameron visiting Cornwall. He was asked a question about the gulls and said there should be a national conversation about them.”

That was 2015, the summer when gull attacks were the silly season story du jour. Barely a day would go past without some horrific attack straight out of Alfred Hitchcock’s movie The Birds… based, of course, on a short story by Cornwall’s own Daphne du Maurier. Whitehead says, “People often talk about gulls being aggressive, but they’re not setting out to attack people. They’re often fed by tourists, and they can’t distinguish between a chip or a bit of pasty that’s being offered, or just being carried. They’re clever, but they’re not that clever. And they do lack manners.”

Still, these aren’t small birds. Imagine your cat, covered in feathers with a long beak and two scaly legs. They’re that big, just not in any way cat-like. But for all their size and noise and fuss, they’re also sort of invisible. We expect to see seagulls at the seaside, just like we expect to see rock pools and seaweed and a family having a subdued argument over the right way to dismantle a beach tent. Gulls are crayoned Vs in a child’s picture of the beach, they are rendered in wood and ranked on the shelves of the gift shops, their distant cries are the soundtrack to your holiday.

What we don’t expect is that they are actually going to attack us. To attack us in our very mouths. But what can be done?

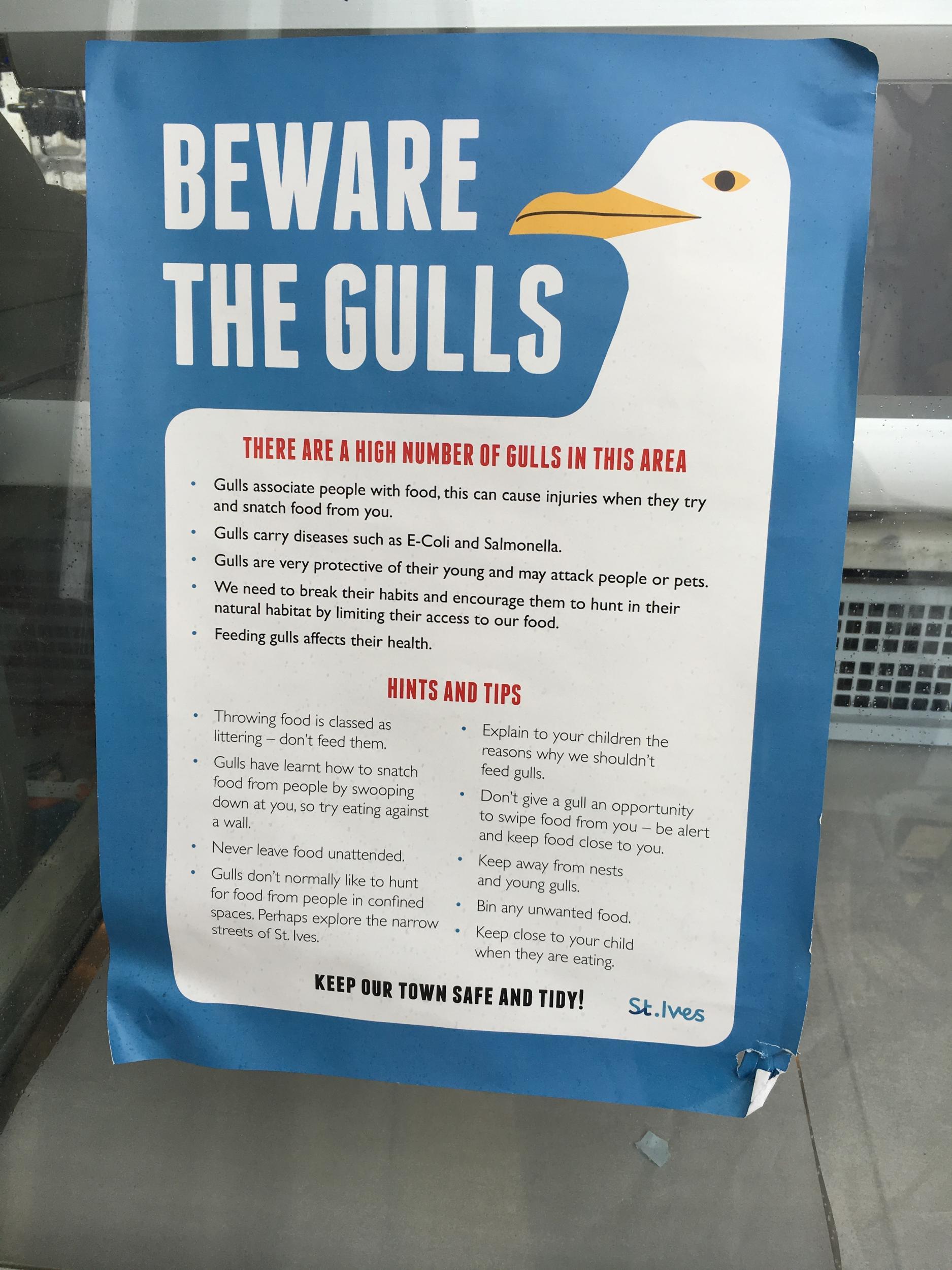

“The town council does not have any control over the actions of seagulls,” says the website of St Ives Town Council, rather apologetically. Well, quite. I don’t think anyone was actually blaming the local burghers directly, nor expecting the councillors to go out and have a quiet word in the gulls’ shell-likes. Still, they do have some advice, and have created a leaflet to help both residents and holiday-makers, saying: “Having had to deal with requests about the aspects of their behaviour which cause a nuisance to people, we are able to give seagull advice. It is also advisable not to feed the gulls, and to either avoid eating outside, or eat outside with care, as the gulls commonly swoop to snatch food.”

And it isn’t just the food, says the Town Council: “Seagull colonies can present problems including noise nuisance, fouling washing and cars and even swooping at people, usually to protect the gull’s chicks or to snatch food. There can also be damage to roofs and gutters, and blockage of gas flues by nesting materials can have serious consequences if gas fumes are prevented from venting properly.”

Which all sounds pretty serious, especially if you’ve just hung out a load of washing. So, again, what can be done? Kill them, says one Facebook group. Kill them all.

“Seagulls might be a protected bird, but I strongly disagree with this,” writes the founder of the We Need A Seagull Cull page. “They are proving to be more like a pest everyday. They dig the hell out of our weekly bin bags, and are causing disease, apart from randomly attacking people, especially when they have their young nesting on our roofs. They are known as rats in the sky, so it begs the question why are we protecting rats in the sky? Are we going to wait until we have a modern day plague? Or a child is hurt or baby killed in its own pram? Let's get our message across to get a law passed to hunt these vermin down.”

Whoof. Strong words. But the un-named owner of the page is quite right, seagulls are a protected species. They don’t, however, have any Royal Charter or anything. “They’re protected just like any other bird, under the Wildlife and Countryside Act,” says Whitehead. “Just to stop people going around killing birds whenever they feel like it.”

That didn’t stop actual armed vigilantes taking to the streets to sort out the gull problem, at least according to Anne-Marie Trevelyan, the Conservative MP for Berwick-upon-Tweed (proving this is a nationwide problem, not one restricted to Cornwall). In February, she told a Westminster debate on the gull issue: “Last summer someone took it upon themselves to institute their own cull, which, while appreciated in some quarters, brought the risk that people are having to take the law into their own hands to deal with these really difficult and aggressive birds. Which means there are people wandering the streets of Berwick with firearms who really shouldn't be doing so.”

And there are provisions in place for culls, or bird control, where needed. Licences can be issued in cases of, say, gulls interfering with agriculture or air traffic control.

Of course, this is utterly a problem of our own making. The gulls are the Frankenstein monsters created by the prevalence of nesting sites, waste and plentiful food that come with any built up human area, especially by the seaside. We might prefer them to be out plucking pilchards from the sea and looking scenic on our postcards, but the fact is we’ve taught the gulls the very worst of human nature. Why forage for your own food every night when there’s a McDonald’s next door?

According to Whitehead, though, the gulls we see eyeing up our suppers in seaside towns are a minority; the majority of gulls still feed on fish straight from the sea.

He says: “Gulls didn’t nest in urban areas until the 1930s and 1940s. After the war, the human population increased and the increase in buildings meant suitable nesting habitats were created for them in towns. This also meant the gulls were safer from predators, so their own productivity increased with more young surviving.

“The food aspect is really a bonus to them. They’ve started to see humans as a source of food, through waste and through people feeding them. A lot of councils are doing good work in not having waste left on the streets for too long and some places are fining people who feed gulls.”

Whitehead believes that through measures like this humans and gulls can learn to live alongside each other much more peaceably. And sitting in the Porthminster Beach Cafe, I can acknowledge that they are often rather splendid creatures, clean and sleek and quite noble looking.

Then one nudges with its beak a whole double-scoop of rum and raisin ice cream that it’s knocked off the waffle cone of a distraught child, rolling it in the sand and then scarfing it down its gullet in one gulp. The sight quite puts me off my bacon, brie and cranberry panini, and I order another bottle of Tribute. Thus far, the gulls have not taken to stealing beer, as far as I know. Now there would be a nightmare of truly Hitchcockian proportions, and you can guarantee that if that day ever arrives, the war between the humans and the gulls will truly step up a notch.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks