How to transform 100 million hectares of hostile desert to a flourishing, welcoming savannah

Complete regeneration is one of the most challenging tasks – the key is to engage local restoration groups and communities in the area

After 14 years, the Great Green Wall is back on the agenda. The ambitious project, launched in 2007, aims to restore 100 million hectares of degraded land in the Sahel, one of the world’s poorest regions, with a target date of 2030.

We’re nine years away from the deadline and it’s hard to keep tabs on what’s been achieved so far. However, in January the French Government, African Development Bank and the World Bank clubbed together to offer over $14 billion to accelerate the initiative and make it a reality. But it will take more than money to restore this land from a tough desert into a thriving, vibrant savannah ecosystem.

Where to begin? Well, let’s start with the numbers. 100 million hectares sounds like an overwhelming figure to restore, but it can be broken down into different parts. We don’t need to plant 100 million hectares worth of trees and grasslands – probably about 30 per cent needs complete restoration, which means reclaiming the land from hostile desert into an actual habitat.

A further third of the land needs partial restoration to improve, for example, river catchment areas, whilst the rest of the land needs to be conserved to prevent it from turning into desert

Complete regeneration is one of the most challenging tasks. The key is to engage local restoration groups and communities in the area.

In Burkina Faso, which includes parts of the Sahel, Hommes et Terre is one of the largest restoration companies hectare-wise in the region, who works closely with local communities to bring the land bank from the brink. Villagers collect the seeds for tree species and grass as well as organic fertiliser, and help to dig half-moons in the desert to collect rainwater.

After a few months in the rainy season, the seeds begin to sprout and start the process of reclaiming the desert into savannah. In the years after, the sites need close monitoring, protection of the local people and sometimes further restoration to slowly make it develop back into a productive system.

Since we began working in Burkina Faso, we are now restoring over 15,000 hectares of desertified land. This work has improved soil fertility and water availability in some of the driest regions of the country, whilst also providing employment and crops to local communities. A strategy like this would be essential to the Great Green Wall project, helping to bring the Sahel back from the brink through the regeneration of trees and grasslands, as well as providing opportunities for those who call it home.

But, when it comes to restoration, the focus is on working with local communities. Without their buy-in and collaboration, as well as agreement on the benefits the work will bring to the local area, any and all activities will be fruitless. For the people who live in the Sahel, the land provides food for their cattle and goats to eat, as well as firewood.

It’s this that leads to suppressed tree growth as young, regenerating plants are eaten before they have a chance to grow. To make an impact in the region, working with local organisations and communities ensures areas can be restored, new seedlings can be managed and the land has a chance to regenerate, for the benefit of all.

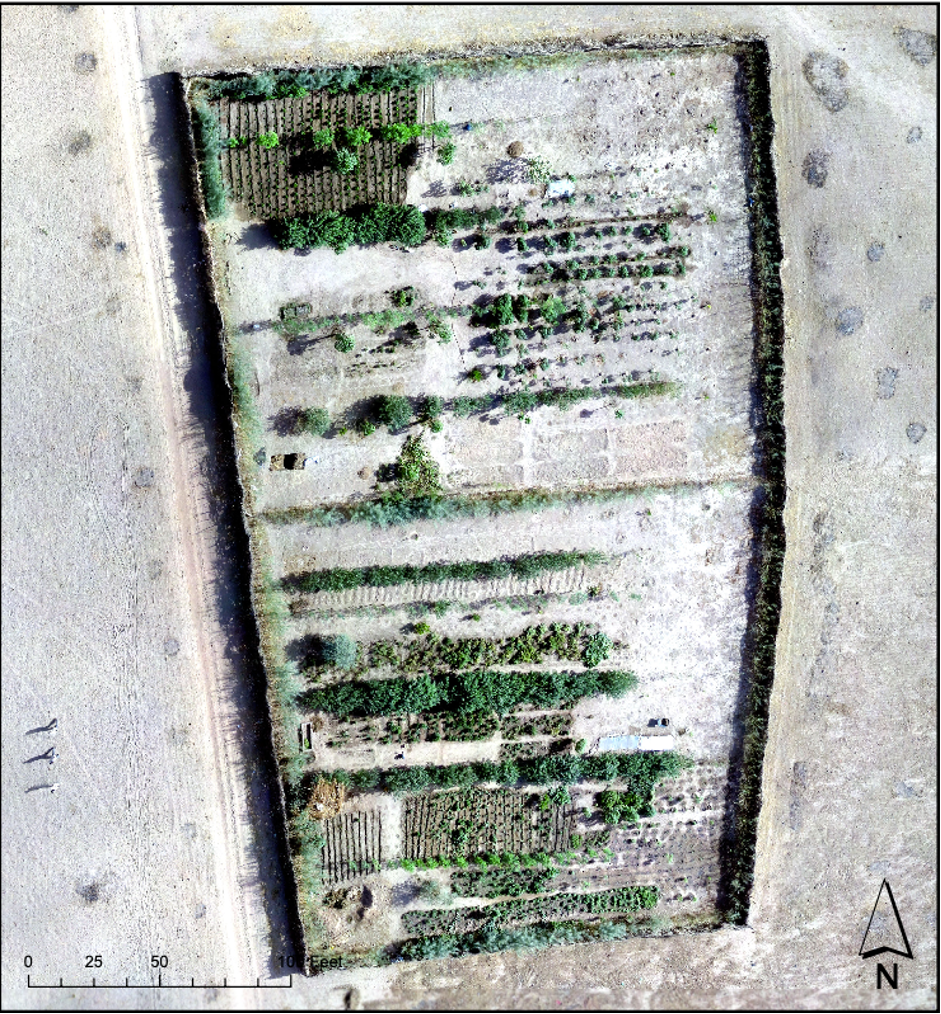

For instance, in Senegal, Trees For the Future help farmers transform single-crop fields into Forest Gardens. These can contain up to 4,000 trees and different fruit and vegetable species, with the trees helping to provide shade and moisture as well as protect the crops. The Forest Gardens revitalise the soil and enhance biodiversity, whilst also providing multiple sources of food and revenue for farmers, instead of one crop. This takes time and collaboration, but it's essential to the success of a multi-benefit project.

Aside from the restoration work, monitoring and managing new growth is just as important. With organisations like Hommes et Terre, new trees are monitored using field inventories and satellite tech. If 30 million trees are growing after the first rains, we expect a 30 per cent minimum success rate after three years, because of the tough desert conditions.

However, if 30 per cent is maintained, then other areas will start to regenerate naturally. Monitoring is just as critical to the project to ensure the grasslands and trees can realise their potential.

Why is planting for the future necessary, you may ask? The investments made now in the Sahel will have a positive impact on climate, biodiversity and the livelihoods of people across the region. Species that live in the area will have their habitat back. Many of the European bird population, who use the African-Eurasian Flyway spend time feeding in the Sahel in the Northern hemisphere winter, benefit from the work.

Improving the soil also means improving the capacity for the ground to capture water, so that during the annual rainy season, water can be stored in the soils instead of all running into rivers and dispersing into the sea. Bringing the grasslands back will help the area sequester more carbon dioxide. You basically get a new set of lungs for the Earth.

There are intrinsic barriers that will hinder the work to create the Great Green Wall (GGW). Terrorist groups are rife in the region, so safety is a concern. Utilising local organisations that have capacity and can scale their work is critical. Not many organisations know how to do projects on such a scale that affect so many people, and do them well.

We need to ensure the money is being used effectively and restores natural ecosystems as well as bringing value to the local people and monitoring and supporting the growing roots. The $14 billion can cover a significant part of the restoration. For example, to facilitate the planting of one billion trees in the region by 2030, running costs for the GGW project would be in the region of 56m euros (500 million over the course of a decade) per year.

If we can put these initial funds to good use and show the money is being spent positively, then that will surely pave the way to fund the rest of the project.

The work of the Great Green Wall will have consequences beyond the Sahel where desertification is a challenge, such as the edges of the Amazon region, but also for example in areas in India and China; where the lessons learned in the Sahel could be replicated to reclaim the land from being degraded there, too.

There’s a long road ahead to achieve the goal of restoring and regenerating 100 million hectares across the Sahel. But, with a combination of partners, technology, knowledge and funding, it will be possible to restore the region from hostile desert and to a flourishing, welcoming savannah.

Pieter van Midwoud is the chief tree planting officer at Ecosia

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks