Even in the far reaches of the Indian Ocean we can’t escape plastic waste – we need coordinated action to tackle it

The most dire projections suggest our seas may contain more weight in plastics than fish by the year 2050 – we need creative measures on land and at sea to reduce it

Last week, the Arctic Sunrise passed through an exquisitely still stretch of ocean known to sailors as the doldrums. Around the solar equator, this region is notoriously absent of currents and wind, and historical accounts tell of sailboats stuck for weeks in the vacuum. It is also known as King Neptune’s realm, and as we approached the crossing from south to north, mysterious signs appeared around the boat requesting that the sea king allow a smooth transit.

Tales and rituals like this connect us in history to others who lived and worked on the water, as the oceans connect people across the planet today; through currents, climate and trade. The Gulf Stream, a current born in Mexico, shapes the climate of Northern Europe. A shipping container blocking the Suez canal for six days impacts global trade for months. And a proportion of the plastics that run off land into rivers and seas coalesce into floating garbage patches the size of Texas – far from their place of origin.

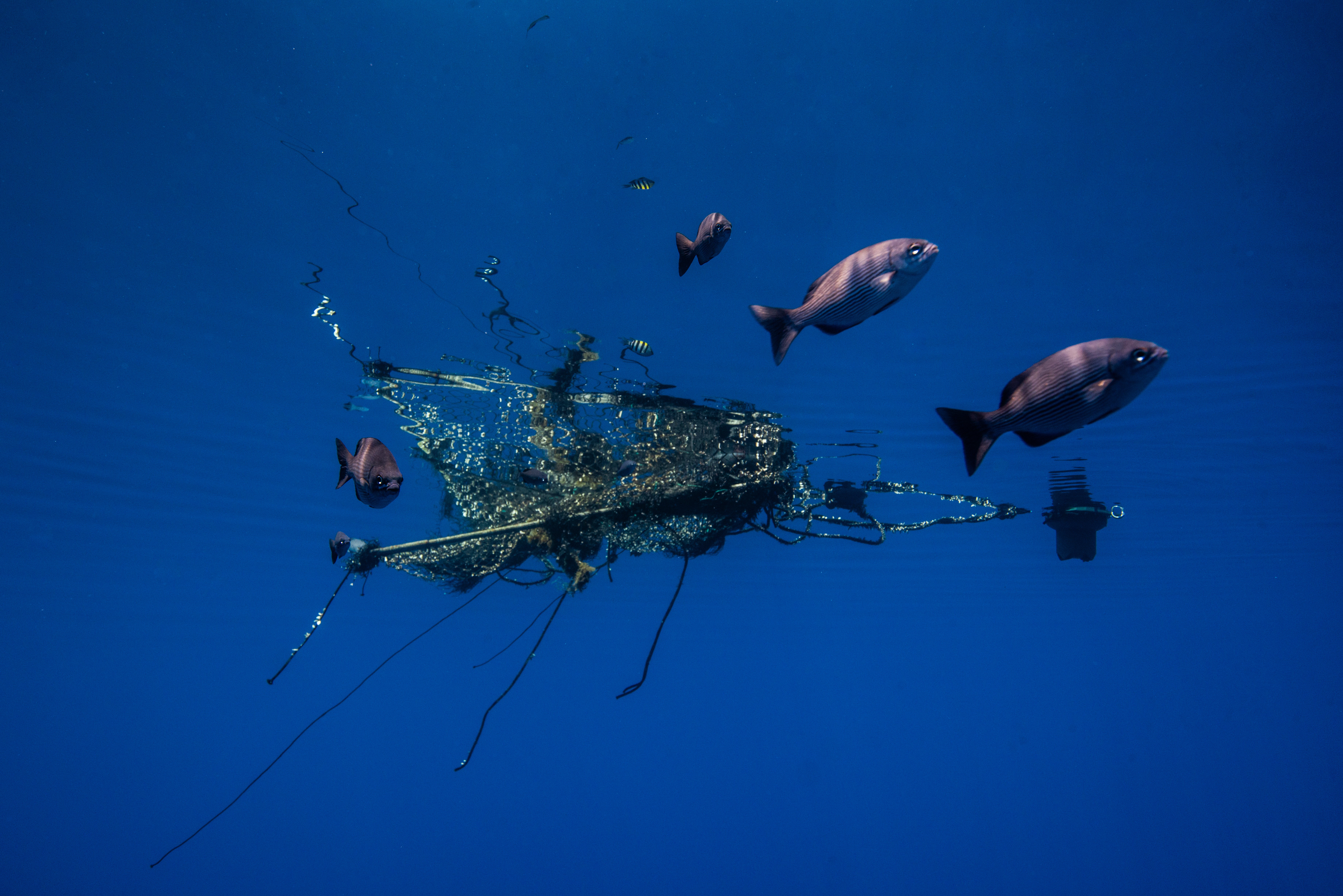

As we moved out of the doldrums, I noticed a significant increase in the amount of plastic floating on the water. We were still far from land, and the sight of it felt jarring against the pristine blue: a reminder that human impact is extensive and few places – even the far reaches of the Indian Ocean – remain untouched.

Plastic rubbish like this enters the seas through a number of mechanisms. About 80 per cent originates on land and runs into the sea mostly as a result of poor waste management; and driven in no small part by single-use items such as water bottles, plastic bags, and food containers.

Discarded nets and lines known as “ghost gear” continue to haunt fish in the ocean, and make up some 10 per cent of all ocean plastics. The problem is extensive: the equivalent of a garbage-truck of plastic is dumped in the sea every minute, and the most dire projections suggest that our seas may contain more weight in plastics than fish by the year 2050.

Plastic doesn’t decompose, both a design feature that drives its extensive use, and a major flaw for environmental stewardship. According to Greenpeace, every piece of plastic ever made still exists, and many make it into our waters. Once in the ocean, some plastics float, like the bottles and containers I have seen out on the high seas; others break down into tiny particles known as microplastics.

There are disastrous consequences for ocean ecosystems. Beyond the images of birds and turtles with six-pack plastic rings around their necks, the abundance of microplastics in the oceans is often mistaken for food by marine life. Animals eating plastics can starve because the plastic can’t be digested, filling their stomachs and limiting their nutritional intake. One whale was found washed up dead on a Scottish beach in late 2019 with 100kg of plastic fishing nets and rope, packing straps, carrier bags and plastic cups in its gut.

This has knock-on effects for the fish eaters among us. A study in Scientific Reports found plastics such as nylon, polystyrene and polyethylene present in a selection of fish and seafood usually consumed by humans. Microplastics can act as a medium to facilitate the transfer of toxic compounds such as heavy metals and organic pollutants, which can cause harm and toxicity when eaten.

In our relationship to plastics, like much of our relationship to natural resources, the approach of extractive capital has been to act as if we live in an open system of limitless supply with an endless capacity to deal with waste. Clearly, that is not the case.

Our planet mirrors the finely tuned balance of our bodies – with feedback loops and systems to maintain it. But we are consuming at too high a rate for the planetary limits we live within; and in our small, cushioned world, waste products accumulate and knock our planet into a critical state.

Ocean plastics have gained public attention in recent years through the most unlikely enemy: the plastic drinking straw. But if we are to tackle the plastic waste crisis, we need more extensive action, particularly in light of the uptick of single-use plastics we have deployed through gloves, aprons and masks in response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Hope comes in the most curious of forms. I’ve been in touch with a boat called the FlipFlopi – a traditional Swahili dhow boat, built with single-use plastic waste, which sails around East Africa showcasing the benefits of a circular economy and the alternate uses of waste plastic.

It is ingenuity and creativity like this that gives me hope our ecosystems can be restored: with action on land to reduce the use of plastic, and action at sea – through measures like a strong Global Oceans Treaty negotiated this summer – to give our oceans the protection they urgently need.

Dr Rita Issa is an NHS GP and onboard medic for Greenpeace’s boat Arctic Sunrise. This is the fourth article in her series from the Indian Ocean for the Independent: read the others here

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks