For one day, a fractured country will be united by sun, moon and history

On 21 August, the United States will see its first coast-to-coast eclipse since 1918. Michael E Ruane surveys the small towns and overlooked landmarks now suddenly thrust into the spotlight

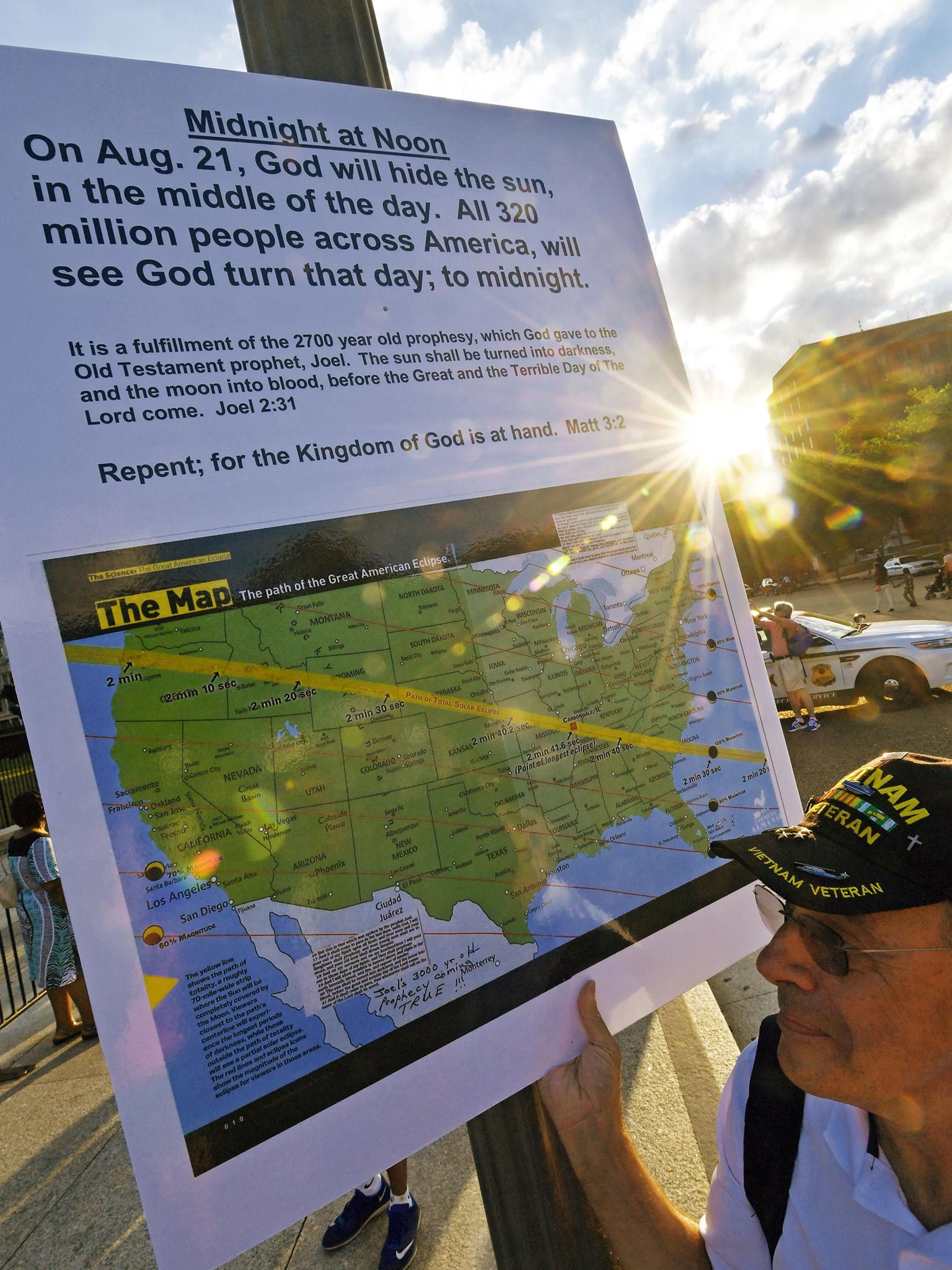

On Monday 21 August a total solar eclipse will be visible, within a band, across the United States. It will only be visible from other countries as a partial eclipse. The centreline will begin at 10am Pacific Daylight Time on the rugged coast of Oregon near a place called Depoe Bay, where 40 ton grey whales spout and feed in the shallow water. At 2,000 mph the line, like one down the middle of a motorway, streaks inland south of Salem, Massachusetts. It goes over an extinct volcano in Idaho, a Stonehenge-like sculpture of junked cars in Nebraska, and crosses the Missouri River blocks from where Jesse James was killed.

Weather permitting, the centre of the 70-mile-wide band of totality will deliver the most seconds of complete eclipse, experts say, as it links a fractured country for one day on a path of history, geography and the racing shadow of the moon.

“When the Earth reminds us that there are tremendous forces out there beyond our control, it helps us to remember who we are,” said Cheri Ward, 56, who has a blueberry farm outside McClellanville, South Carolina, near the path’s centre.

Along its 2,500-mile journey, the line crosses the winding Missouri River eight times. It traverses the old steamboat port of Arrow Rock, Missouri, home of painter George Caleb Bingham, who portrayed life on the river in the mid 1800s.

The line crosses the Cumberland River twice, and the Mississippi once at a coal terminal on the Illinois side, not far from where Elzie Crisler Segar, creator of the cartoon character Popeye, was born.

It passes Mantle Rock, Kentucky, where in 1836 hundreds of starving Cherokees waited to cross the Ohio River during their forced migration west on the “Trail of Tears”.

And it crosses the Oregon Trail, the Santa Fe Trail, the Appalachian Trail and the route of the Pony Express. In Tennessee, it goes over Rome, but skirts Athens, Sparta, Carthage, Lebanon and Macedonia. In western North Carolina, it passes just south of the ancient oaks and poplars of the Joyce Kilmer Memorial Forest, named for the man who wrote the poem “Trees” and was killed in battle during World War I.

I think that I shall never see

A poem lovely as a tree . . .

And it exits the country just before 3pm Eastern Daylight Time over Five Fathom Creek, in the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge, with its two aged lighthouses, northeast of Charleston, South Carolina.

The line crosses baseball fields, golf courses, tennis courts, interstate highways, parking lots, driveways and cemeteries, including one in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, where the 20th century mega-psychic Edgar Cayce is buried. It passes places such as Massacre Mountain and Hell Canyon, Mosquito Creek and Tadpole Island, Dawg Patch Trail and Hound Dog Drive.

While the band of totality is miles wide, “it really matters how close you are to the centre,” says Geneviève de Messières, of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. “Along that centreline you have a better chance of experiencing the full glory of the eclipse.”.

One place that will see maximum time of totality, according to data complied on the website Eclipse-chasers.com, is the old railroad hamlet of Makanda, in southern Illinois. Totality: more than two minutes 40 seconds.

The event has “taken a little town that’s not on anybody’s map to ... the centre of national conversation,” says Jeremy Schumacher, who works at the Eclipse Kitchen restaurant there.

Makanda, population about 600, now seems like “the centre of the sun, and moon and Earth and everything,” he says.

This is the first coast-to-coast eclipse in the United States since 1918, according to the Smithsonian Institution. Millions of Americans are expected to converge on totality to observe, clog traffic and munch pancakes, barbecue and pizza. Amtrak is running an Eclipse Express from Chicago south to Carbondale, Illinois.

Commemorative T-shirts and eclipse glasses by the thousands have been made. Many schools will be closed, including at least one that has declared 21 August “a snow day”.

Some locales are wary of the hordes of eclipsers, fearful that small communities and infrastructures will be overwhelmed by hungry people who also have to go to the bathroom. Others see an opportunity to preach, make money or welcome visitors to forgotten waypoints of American history and landscape.

---

In 1852, renowned artist Bingham painted a picture titled The County Election, which is believed to be a portrait of Arrow Rock, Missouri, where he had lived a decade before. It’s a bustling scene outside a small-town polling place in Middle America in the mid-1800s, with politicking, inebriation and children playing in the dirt street.

It was one of many Bingham paintings of those times that portrayed a bygone world of stump speakers, fur traders and flatboatmen on the river. Arrow Rock was then a thriving port of about 1,000 people on a bluff overlooking the Missouri River, and one of the first stops on what would become the Santa Fe Trail for settlers heading west. “People would come across the river by ferry to Arrow Rock and rendezvous with the rest of their party, get supplied and head out,” says Sandy Selby, executive director of Friends of Arrow Rock.

(The centreline of the eclipse goes right over the friends’ headquarters on Main Street, netting two minutes and 39 seconds of totality.)

The town saw heavy river traffic, and Selby says there is at least one steamboat wreck just offshore. She explains that experts have identified many local figures in The County Election, plus the white dog in the foreground, Scamp.

Then the Missouri moved. “Every time it would flood, the river would change course a bit, and eventually it moved about a mile away,” she says.

Then came the railroads, but not to Arrow Rock. The Civil War further hampered trade, and two big fires wrecked the business district. Many residents left.

Today, Arrow Rock’s population is 56, “on a good day”, she said. But 13 of its buildings have been restored. The cottage that Bingham built in 1837 is part of the Arrow Rock State Historic Site. And the whole village is a National Historic Landmark.

“We’ve found a new life as a historic venue ... that really was unexpected and wonderful,” Selby says.

And now the eclipse.

“We’ve got someone coming in from Ireland,” she says. “We’ve got some people coming in from Canada ... We’ve had people calling from all over. They want to be here. Or they want to be somewhere on the line.

“If you’re coming from Ireland, you don’t want to be a mile away from the line. You want to be on the line.

“My hope is that when it happens, that people will be quiet. That for two minutes and 39 seconds we’ll have silence, and we’ll take that time to just reflect on how special this is.”

---

On the high plains of northwest Nebraska, north of Alliance, where Army pilots trained in the Secopnd World War, a mysterious circle of grey objects rises from the flat expanse of farmland. The objects closely resemble Britain’s 4,000-year-old Stonehenge, a mystical place of pilgrimage for neo-druids, solstice watchers, and legions of tourists. But this monument is made of 39 junked cars. It’s Carhenge, perhaps the most cosmic spot in the country to watch the eclipse. And it has an impressive two minutes and 28 seconds of totality.

Carhenge was assembled in 1987 by Jim Reinders, the son of a Nebraska tenant farmer, to honour his late father, Hermann. Reinders, 89, a retired oil industry engineer now living in Texas, resided in London in the 1970s and was fascinated by Stonehenge.

After his father died, he came up with the idea of Carhenge, and in June 1987 members of his family convened on land he had inherited from his father. “With about 30 of us working at it, why, in one week later, we had Carhenge up and running,” he says.

A year later, he hired a painter to spray paint everything “Stonehenge grey”. He used cars because stones are heavy and not abundant on the farm. “Cars are more or less the same size,” he explains. “They had the added advantage [that] they had wheels on them. So it made it a lot easier to move them around.”

Plus, “there’s plenty of junked cars in America”. Many farms in the area had old cars parked outdoors, and the owners were happy to get rid of them. Construction went well, except when an AMC Gremlin that was poorly welded in place came down in a storm. It was put back with stronger welds, Reinders says. He plans to be at Carhenge on Monday, reportedly along with Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts and thousands of others.

But the creator of “Stonehenge west”, as he calls it, sees no mystical aspect to the eclipse. “It’s an astronomical fact that’s been predicted for hundreds of years, and they know when the next one will be,” he says.

“I don’t see any significance to it whatsoever. It’s just an event that will happen every 99 years, or whatever.

“Let’s enjoy it.”

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks