The Big Question: Should the Government be allowed to hold so much data on its citizens?

Why are we asking this now?

The balance between civil liberties and security is always a delicate one; over the past few days, the Government's view of how to strike it has been called into question. In four separate developments, the Government has tried to expand its hold on the private information of its citizens, while campaign groups and European bodies have attempted to hold it back.

What are the issues in question?

On Wednesday, the Queen's Speech included a provision that the barriers to public bodies sharing information be drastically reduced, which would mean that institutions from the police to the Inland Revenue could freely exchange details of citizens without their additional consent. It also scheduled a consultation paper for January that is expected to moot a giant database of people's personal communications, including telephone calls and emails. Then, yesterday, the Council of Europe's Commissioner for Human Rights, Thomas Hammarberg, released a report on the right to privacy across Europe that issued a damning verdict on practices like Britain's. And, 17 judges at the European Court of Human Rights agreed unanimously that the British police had erred in retaining the DNA and fingerprints of two men who had not been convicted of any crime.

What did the human rights commissioner say?

He takes a dim view of the situation here. "In the UK," he says, "DNA is taken from everyone who is arrested, and retained even if they are exonerated of the crime in question." Combining such information with other databases, he says, "creates a previous unimaginably detailed picture of our lives and interests, cultural, religious, and political affiliations, financial and medical aspects. Yet the data protection safeguards against the transferring of information are weak". The report also establishes a general principle: "Personal data should never be collected by the police or other law enforcement agencies 'just in case'."

And what exactly do the Government's new plans entail?

Something not a million miles away from the state of affairs that Mr Hammarberg worries about. The Ministry of Justice's response to the Data Sharing Review Report, which is the basis for the legislation referred to in the Queen's Speech, explains that the aim is a "more streamlined process", and says that new legislation will "confer upon the Secretary of State a power to permit or require the sharing of personal information between particular persons or bodies, so long as a robust case can be made to use that power".

It may even be possible for private companies to gain access to data that has been gathered by the state. The report leaves open the possibility of the Government taking such concerns to parliament on a case by case basis, but since such detailed consideration would probably be impractical, it is more likely that approval would be sought for the transfer of wider classes of data between different bodies.

What do opponents say?

They are somewhat sceptical of the Government's ability to self-regulate. "This is a Bill to smash the rule of law and build the database state in its place," said Phil Booth, national co-ordinator of civil liberties campaign group, NO2ID. And David Howarth, the Liberal Democrats' justice spokesman, pointed to the Government's record on data loss as a further reason to oppose the change. "Unrestricted data-sharing simply increases the risks of data loss... the Government has already shown itself entirely incapable of keeping our personal data safe," he said.

How does the Government defend the charge?

The Ministry of Justice says the moves are necessary for more efficient public services that would better protect the public. It adds that such data-sharing would occur "only in circumstances where the sharing of information is in the public interest and proportionate to the impact on any person adversely affected by it."

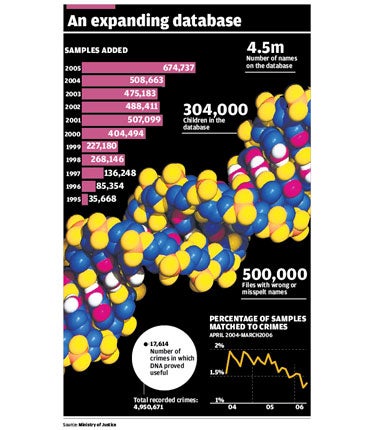

What about the DNA database?

The case before the European Court of Human Rights was brought by two men who had their DNA and fingerprints held by South Yorkshire Police despite not having been found guilty of any crime. (One had been accused of harassment, the other of attempted robbery.) In awarding the two men £36,400 each, the judges said holding such data "could not be regarded as necessary in a democratic society". To the Government's vexation, that verdict now stands alongside the opposition political parties and a majority of public opinion. But there is no doubt that the database has helped to solve some crimes. According to the Home Secretary Jacqui Smith, it provides 3,500 matches between crime scene samples and people on the database every month; Chief Constable of Staffordshire Chris Sims, of the Association of Chief Police Officers, said 200,000 database samples threw up 8,500 matches and helped to close cases including 114 murders and 116 rapes.

What does this verdict mean for the database?

The obvious conclusion is that anyone who is on the database but has not been found guilty of a crime now has a case against the Government – a headache-inducing prospect for Ms Smith, since about 900,000 of the estimated 4.5 million people on the DNA database do not have a criminal record. Scotland already destroys the DNA of those who have not been found guilty; for now, Ms Smith says, the law will stay in place while the Government considers whether its position is consistent with the verdict. Peter Mahy, solicitor to the two men, said "the Government should now start destroying the DNA records of those people who are currently on the DNA database and who are innocent of any crime".

What future changes to legislation on personal data can we expect?

The next major battleground will be January's Communications Data Bill. The proposal to create a database of all electronic communications in the UK has already attracted significant controversy, both over its potential cost – up to £12bn – and its civil liberties implications. The proposed database has already been described as "extremely dangerous" by Lord Ashdown, and the civil liberties lobby is lined up to fight against the introduction of a crime-fighting weapon that many see as potentially totalitarian.

Is the Government at all cowed by these setbacks?

It doesn't seem to be. Ms Smith continues to see innovations like the database as vital parts of the modern police toolkit. The sharing of information between agencies provides valuable efficiencies at a time when the Government is looking to save every penny it can. But opposition to such measures shows no sign of fading away. "All of us are increasingly placed under general, mass surveillance, with data being captured on all our activities," Mr Hammarberg wrote in his report. "Such general surveillance raises serious democratic problems which are not answered by the repeated assertion that 'those who have nothing to hide have nothing to fear'."

Is so much information necessary for the state to ensure our security?

Yes...

*A significant number of crimes would go unsolved without the use of DNA and communications data

*Little evidence is more compelling or irrefutable than DNA or a self-incriminating communication

*Organised criminals are increasingly sophisticated. The police cannot defeat them if it is hobbled

No...

*There are many other steps that might increase conviction rates, like torture; we still don't sanction them

*It isn't worth the cost, to the public purse or to our civil liberties, to bolster cases that might be won anyway

*Taking so much information from innocent people may make them permanently resentful of authority

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks