Britain's lasting vision of the past

An ambitious survey of British postwar design shows just how much today's architects and artists owe to their innovative forebears, says Jay Merrick

How much has British design changed since 1948? The poster for the so-called Austerity Olympics in London that year showed a statuesquely naked athlete, coiled and about to release his discus towards Parliament. In 2012, the Olympic logo is designed to allow sponsors' corporate colours to be used in the symbol. How did we get from a broadly civic, welfare-minded postwar design culture to 21st-century industries whose essential purpose is to make as much money as possible?

It's a complicated story and the V&A's new blockbuster show, British Design 1948-2012: Innovation in the Modern Age, is timely and ambitious. Its 300-plus exhibits sample the genetic material of design through this 64-year period, and Christopher Breward and Ghislaine Wood have curated a series of overlapping windows on tradition, modernity, subversion and innovation.

This show will be a must for students, and a trip down visual and emotional memory lanes for anybody who knows the best of 21st-century British design owes almost everything to a stream of bold artistic and manufacturing experiments in a UK that still smelled of Spam, Player's Navy Cut cigarettes and Brut aftershave. This sense of design as a series of surprising experiments has largely vanished into a profitable haze of ironic, mass-affordable designer gubbins – Philippe Starck lemon juicers, wellies, 4WD vehicles with bull bars and tough names, such as Raptor, for city dwellers.

It's the first time that postwar design in Britain has been portrayed in such detail – indeed, the V&A had to acquire almost 40 iconic objects at a cost of more than £60,000 to create a sense of cultural completeness. Fanatics will palpitate at the prospect of seeing originals such as Ernest Race's Antelope steel rod bench from the 1951 Festival of Britain; Alexander McQueen's astonishingly lush, digitally printed Horn of Plenty dress from the Noughties; Frank Bowling's hallucinatory 1966 painting, Mirror; and Brian Long's still astonishing 1971 Torsion chair.

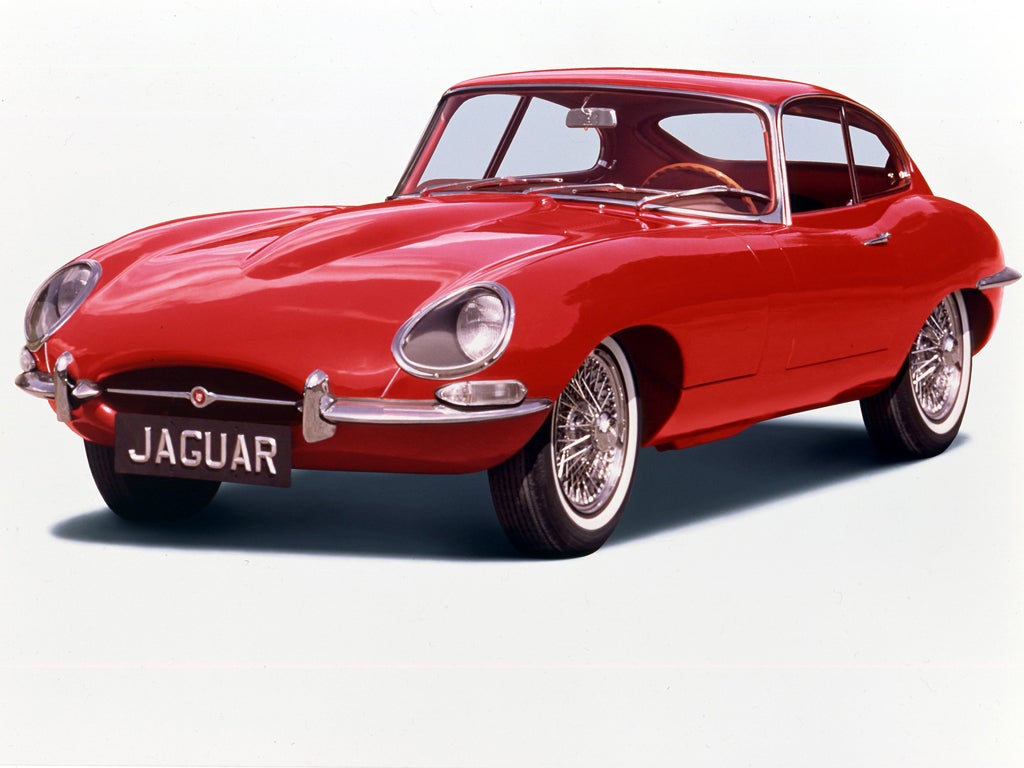

Today we take this kind of innovation for granted. But in the Forties the idea of well-designed products for the public was relatively novel. Could anything be more purely shock-of-the-new than James Gowan's drawing of the Skylon, the quaintly named "vertical feature" of the Festival of Britain? You want Brave New World? Try Henry Moore's stolid Family Group on the concrete plaza in Harlow new town. Fab gear London in the Sixties? No problem: the V&A show will allow you to touch the first E-Type Jaguar exhibited at a motor show.

The Festival of Britain may have introduced the public to the possibilities of a postwar modernist fantasy world, but if there was a seminal moment, it was probably the now-legendary This Is Tomorrow show at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1956. Here, for the first time, a largely unsuspecting public encountered super-savvy, self-critical design – most famously Richard Hamilton's collage Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? A bare-breasted woman wearing a lampshade for a hat, a cut-out of bodybuilder Charles Atlas, a tape recorder... what, only two years after the end of rationing, could this possibly mean? Hamilton had seen the future, and that meant design that was low-cost, expendable, glamorous – and big business.

In the Sixties, Britain's first hip architecture critic, Reyner Banham, eulogised a new ethos in which plastic, steel, aluminium, neon, inflatable homes, napalm, the superficial, and "the voice of God as revealed by his one true prophet, Bob Dylan", were all groovily sacred and profane. The conservative architectural historian, Nikolaus Pevsner, deplored this excessive stimulation: "We cannot, in the long run, live our day to day lives in the midst of [design] explosions."

But we have, and do, and the V&A show will be full of them. The balsa wood model of the ziggurat-like halls of residence at University of East Anglia; Her House, a 1959 design for a 1,070 sq ft home costing £3,000; the 1968 "Don't Let the Bastards Grind You Down" poster from Hornsey School of Art; David Bowie's 1973 stage costume, designed by Kansai Yamamoto; Brian Duffy's "How to Undress in Front of Your Husband" cover shot for Nova magazine in 1985. These may seem predictably retro examples, but they arose in a highly charged climate of creative objection and change that was increasingly forced by art and design students themselves.

It's disappointing that the show's set-piece architectural exhibits are rather safe. There can be no objection to featuring the mod-baroque espresso machine otherwise known as Richard Rogers's Lloyd's Building, or Zaha Hadid's Olympic aquatics centre – even if the velodrome is just as remarkable. But is Noman Foster's 30 St Mary Axe (aka the Gherkin) really as innovative as his Willis Faber headquarters was in the Seventies? And why feature the Falkirk Wheel when the instantly iconic structure of King's Cross station's new western concourse will be used by tens of millions of travellers – and perhaps even an Olympic discus thrower or two?

British Design 1948-2012: Innovation in the Modern Age, V&A Museum, SW7 (020 7942 2000), 31 March to 12 August. A book, edited by Christopher Breward and Ghislaine Wood, is published by the V&A

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks