How a family tree could save your life

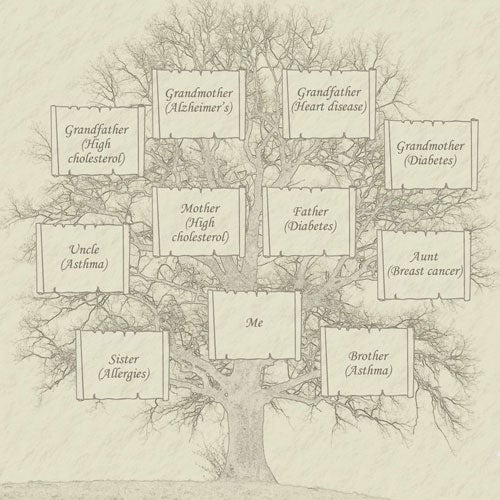

Finding out which illnesses afflicted our forebears can tell us more about the risks we face than genetic tests. Hugh Wilson reports

The word Alzheimer's is not one you skip over lightly, especially when it appears in a document describing the illnesses and infirmities that have afflicted your own family. But Alzheimer's makes an appearance twice in a family history that, so far, covers a total of 15 people. I knew that my aunt had died of the disease in her 80s. But my grandfather on my dad's side died before I was born, and I had been blissfully unaware that he had also succumbed to Alzheimer's – and at a frighteningly young age.

But there is good news, too. A little research and a long chat with my mum (who knows about these things like a good matriarch should), have produced a basic family health history, covering my children, sibling, parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles on both sides and some of my cousins. There is only one mention of cancer and no heart attacks. If there is heart disease and high cholesterol in the immediate family, it has never been severe enough to creep into the collective memory, and certainly nobody has died of it.

So far, so OK. I'm digging about in recent family history for the good of my health, of course, and for the good of my children's health. Family health histories have recently been called "the best kept secret in healthcare", after new research discovered that a good one can trump costly genetic testing in predicting what illnesses you and your children may face.

In the study, carried out by researchers at Cleveland Clinic's Genomic Medicine Institute in Ohio, 44 people were asked to produce accurate family health histories and have a saliva swab sent for genetic testing, to calculate their risk for colon cancer and breast or prostate cancer.

Both methods suggested about 40 per cent of participants had a higher than average risk. But they didn't pick the same people. In the colon cancer test, for example, the swab missed all nine people with a family history of the disease, five of whom were later found to have a specific gene mutation linked to the cancer.

"A good family health history is, and always has been, very accurate for predicting risk of disease," says the clinic's Dr Charis Eng. "Remember the old actuaries? They always said that, and they – and your grandma – were right."

But if the latest research only confirms what we've all known for decades, it does beg the question of why family health histories are not already a standard tool in the GP's armoury? "Family health histories are the cheapest, best way to ascertain disease risk [for certain diseases]," says Dr Eng. "Doctors seem to have lost the fine art of taking accurate family histories. On both sides of the Atlantic, is it possible that doctors feel too rushed because they are called upon to do more with less time?"

GPs would undoubtedly agree that coaxing good family health histories from every patient is one job they could do without. But there's no reason why we can't tap into this powerful health tool ourselves, and experts are encouraging us to start health histories of our own.

Online tools have been created to help (this, from the American Government, is particularly thorough: familyhistory.hhs.gov/fhh-web/ home.action). Creating a family health history online makes it easy to email a copy to your relatives, update it when any new information arrives and print it out to show your GP.

Nor do you have to approach your health history with the fervour of an amateur genealogist with an interesting bloodline. Dr Eng says that, while genetic professionals will often reach back into five generations of a family, for screening purposes first and second-degree relatives are fine. First-degree relatives are children, siblings and parents, with second-degree relatives including uncles, aunts and grandparents. First cousins may be a useful inclusion, too.

But remember, you need to include both sides of the family. Research presented last month showed that women were, mistakenly, more dismissive of the threat of breast cancer if it showed up only in the paternal line.

Once you've created a family health history, you can study it for patterns of illness and show it to your GP if you have concerns. But GP Dr Sarah Brewer, author of the Natural Health Guru series (Wiley), cautions that even strong patterns shouldn't be viewed fatalistically. "Family history can be an important indicator of predisposition to certain diseases – some cancers, heart disease, diabetes, Huntington's chorea and so on. But lifestyle is also important, as the majority of diseases are multifactorial. It's important to remember that diet and lifestyle can often beat genes at their own game."

In other words, a health history can be a call to action. If there turns out to be a history of colon cancer in the family, your diet and lifestyle can work to counter the small increased risk. You can pass that advice on to your children, too.

My own family health history shows a smattering of allergies, as well as asthma, emphysema and bronchitis – though the last two may be smoking-related. Happily, I haven't (to my knowledge) inherited any of them. The osteoporosis on my mother's side of the family is more of a worry to me than to my baby daughter, who will at least be in a position to make early lifestyle choices to mitigate the effects. For the moment, she can take comfort in the fact that six decades of medical advances might render those efforts redundant.

My dad died of bladder cancer, but Dr Brewer says that any hereditary connection is not strong. "Most of the mutations that develop in bladder cells do so during a person's lifetime rather than being inherited." On the downside, she agrees that "Alzheimer's is your strongest potentially hereditary condition, although familial Alzheimer's accounts for fewer than 10 per cent of patients". Should I be worried? At first glance the answer seems to be "very", but more analysis of my family health history provides a bit more comfort. Familial Alzheimer's disease is rare but undoubtedly inherited, and develops before the age of 65.

That happened with my grandfather, but my dad never showed any hint of mental decline and his twin brother lived well into his 70s without developing the disease. "In that case there is a very good chance, assuming your grandad did have an inherited form of Alzheimer's, that your father didn't inherit the causative gene," says Dr Brewer.

Which is good news indeed, though I may be following developments in the field of Alzheimer's research more closely from now on. In the meantime, I'll spend next Christmas pressing cousins about half-forgotten hospital stays and cholesterol counts. It will be my present to the family.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks