David Bailey: 'I don't take pictures, I make pictures'

As a major David Bailey exhibition opens at the National Portrait Gallery, the East End boy who helped create the Swinging Sixties tells Chris Sullivan that his best work is yet to come

As I walk into David Bailey’s rather unpretentious mews studio in London’s Bloomsbury he is hunched over a laptop going through images for his forthcoming exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery. He looks up. “Sorry mate, just be a minute,’ he says. “Do you want to look at the book?” A large tome the size of a paving stone entitled, Bailey’s Stardust, with a multi-coloured cover by Damien Hirst, is dropped in my lap. It is the catalogue or shall we say book of his forthcoming exhibition – its title taken from Hoagy Carmichael’s 1927 song about a love song: “My stardust melody/ The memory of love’s refrain.”

Accordingly, inside the book I see my past, indeed our past, parade in front of me in the shape of portraits of anyone and everyone who has helped form contemporary culture both counter and otherwise: David Lean, Warhol, Dali, Johnny Rotten, David Bowie, Kate Moss and Brigitte Bardot are just some of the names inside; and then there’s a nude section – “Democracy” – featuring among others, Albert John, a gnarly old man who, tattooed all over, sports a good hundred odd piercings on face and testis. Other areas include, “Artists”, “Papua New Guinea” and “Beauty”.

It is an astonishing collection by anybody’s measure that is at once, humorous, brutal, perceptive and refreshing.

“I don’t take pictures,” explains Bailey. “I make pictures. A five-year-old can take a picture. But that is not what it’s about or what I do. I don’t think of myself as a photographer or an artist. I don’t even care how I am perceived. But there is a difference between making pictures and taking pictures. It’s an art. Bruce Webber can do it. Robert Frank can, as did Cartier-Bresson. But photographers come here to take photographs of me and don’t even talk to me. And they take so fucking long. It’s like masturbation for them. I talk to people more than take their pictures. Probably an hour’s talking to 10 minutes of shooting.”

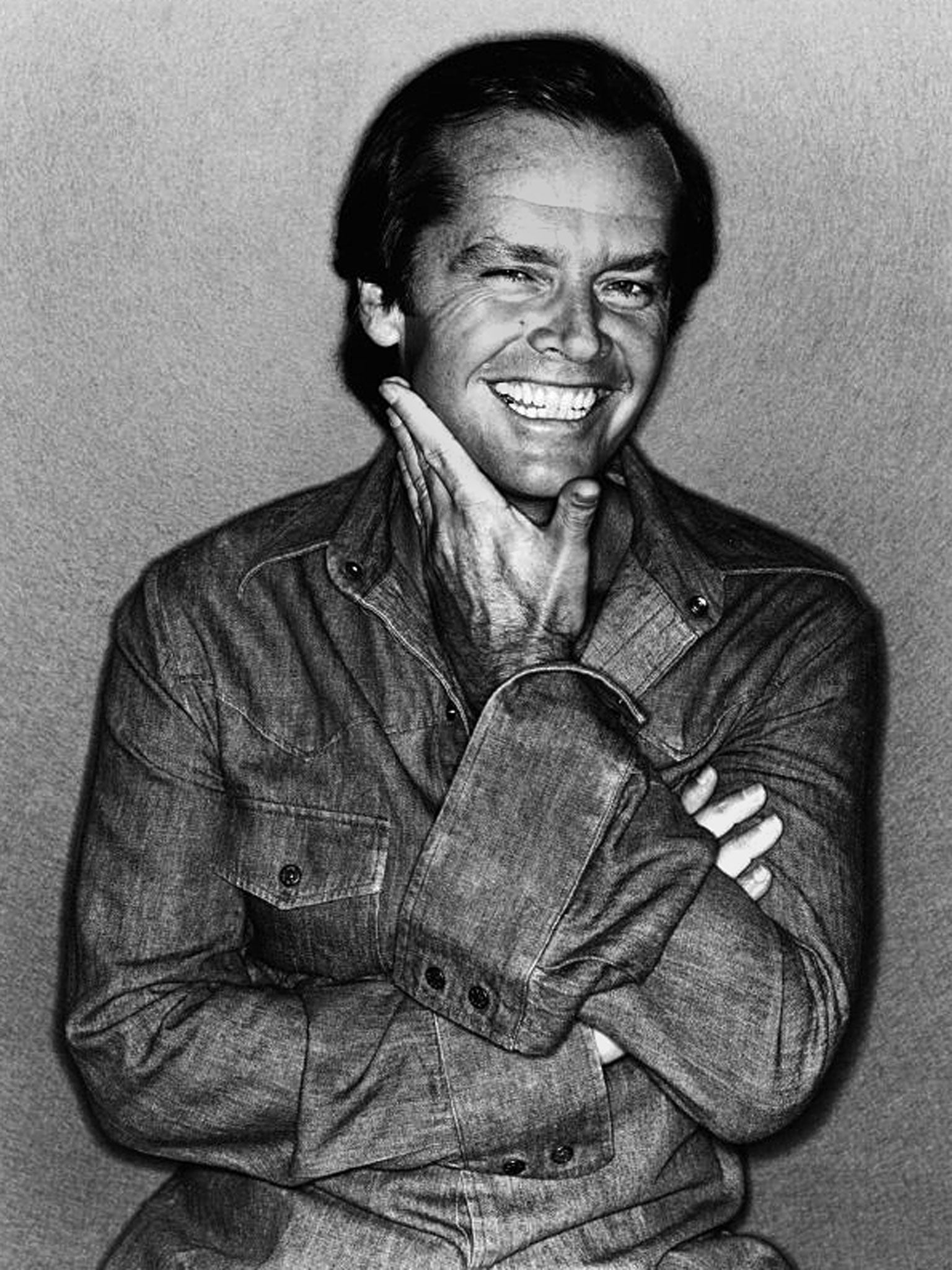

And perusing the myriad images from the book it is apparent that his modus operandi pays off. After viewing the picture-maker’s work, the novelist William Golding, wrote in his preface to Bailey’s 1985 book, Imagine. “I am not sure I shall ever be the same again.” Undoubtedly, his photographs get beneath the skin of his subject’s to reveal more about their character than one might ever expect from a common or garden photo: Cecil Beaton is as camp as a row of tents (“He was really talented but a ghastly man, such a snob, the middle class are the worst snobs”), Jack Nicholson’s infectious smile fills the frame (“He’s the most intelligent actor I have ever met – he knows something the other actors don’t know”) while Francis Bacon looks intense and downright sleazy (“He tried to pick me up in Soho when I was young and I didn’t know who he was.”)

Bailey has spent the last two and a half years going through his vast archive selecting and reprinting his images for the exhibition. Some are a different frame of a well-known image, while the new black-and-white silver gelatine prints jump out of the frame and bite.

Another room in the NPG is devoted to David Bailey’s Box of Pin-Ups – a series of portraits he’d embarked on after he’d split up with model Jean Shrimpton in the spring of 1964 and became bored with fashion. Including the likes of Michael Caine, Nureyev, Hockney and Lord Snowdon, it was initially sold as loose portfolio of 36 shots printed on stiff paper. “As usual I lost money on the project,” he groans. “We couldn’t give it away at the time. Now they sell for £20,000.”

“They [the sitters] were mostly mates,” he explains. “They were the easiest to get to come to the studio.”

Both the Rolling Stones and the Beatles feature in Bailey’s Box. Mick Jagger peers out from under a furry parka while Lennon has his eyes closed.

“I much prefer the Stones to the Beatles but always loved Lennon,” clarifies the lens man.

Undeniably, some of Bailey’s most controversial, iconic and recognizable images are in the Box – namely his truly menacing shots of Sixties East End gang lords, the Kray Brothers, etched against Bailey’s characteristic stark white background. One of these prints looks down from the walls of his studio.

When I ask what they were like, he shrugs. “They were all right. Just East End blokes really, I knew them really well... People ask, ‘How could you like Reg?’ but I did like him. He didn’t do anything to me. Didn’t like Ron so much –I avoided him, ’cos a slip of the tongue and you’d be fucking dead. I saw him beat a bloke almost to death for not offering round the corned beef sandwiches.” He pauses, “One of the worst things Reg ever said to me was, ‘Dave, mate, you’re all right now, you’re on the Firm!’ And I would think: No! Please no!

“I used to see quite a lot of Reg. He even sent me a film script he’d written, a card every Christmas and poems.”

“But these pictures [from the Box] completely stand up and are simply against a white background,” he explains. “Still, they’re the hardest shots to do. You’ve got nothing in the background to help you... but all those things distract you anyway.”

Enormously driven, Bailey admits to working every day (“I was printing on Christmas day,” he laughs) and gave up alcohol and party going some 40 years ago as it got in the way of his work. This is a man who loves what he does and wants to do a lot more.

He was born in 1938 in the solidly working-class east London neighbourhood of Leytonstone. Mother Gladys was a sewing machinist while his father Herbert (“a bit of a rogue”) was a gentleman’s tailor. Bailey remembers little of the war. “We spent most of the time sheltering in Tube stations and coal cellars from the Luftwaffe bombs,” he recalls. We were evacuated to the West Country but my mum couldn’t stand it so we were back in a few weeks looking up watching the V2 rocket as they went over London.”

One of the exhibition’s most endearing sections, “East End”, fields shots of shop fronts, bomb sites and streets in Bethnal Green, Shadwell and Whitechapel taken between 1961 and 1962 – just as the Jewish folk were leaving and way before the Bangladeshis arrived. The difference between then and now could not be more marked. “It looks like fucking Czechoslovakia in 1938,” he comments. “The streets of the East End looked lonely back then.” Alongside the cityscapes are wonderfully insightful colour shots of the area’s characters (“East End Faces”) taken in 1968. “These are just people I met,” he says.

Bailey, who’s just turned 76, didn’t have it that easy growing up in the East End. “It was a bit rough back then,” he snorts. “There were two big gangs, the Barking Boys and the Canning Town Boys. The Barking Boys did me when I was older. Beat me up and left me flat out in the smashed window of a furniture store.”

Previously, he’d been heavily chastised throughout school for his inability to learn. Years later he discovered he was dyslexic. “One teacher told me that someone’s got to dig the roads,” he laughs. Luckily, he was taught how to use a darkroom and by 16 was really interested in photography. “I played the trumpet when I was 14, 15 and I used to take pictures of me trying to looking like Chet Baker in the back yard.” After National Service in the RAF, he was taken on as an assistant with fashion photographer, John French, and by the early Sixties he was shooting Vogue front covers.

Bailey, is not only the world’s most famous photographer, he is also the man who catalogued and defined the Sixties – the decade that changed world’s cultural landscape. I wonder what it was like being slap bang in the middle of the maelstrom.

“ We didn’t really see what was happening as we were right in the centre of it all,” he smiles. “It was all happening so fast we didn’t have time to turn around and see it.”

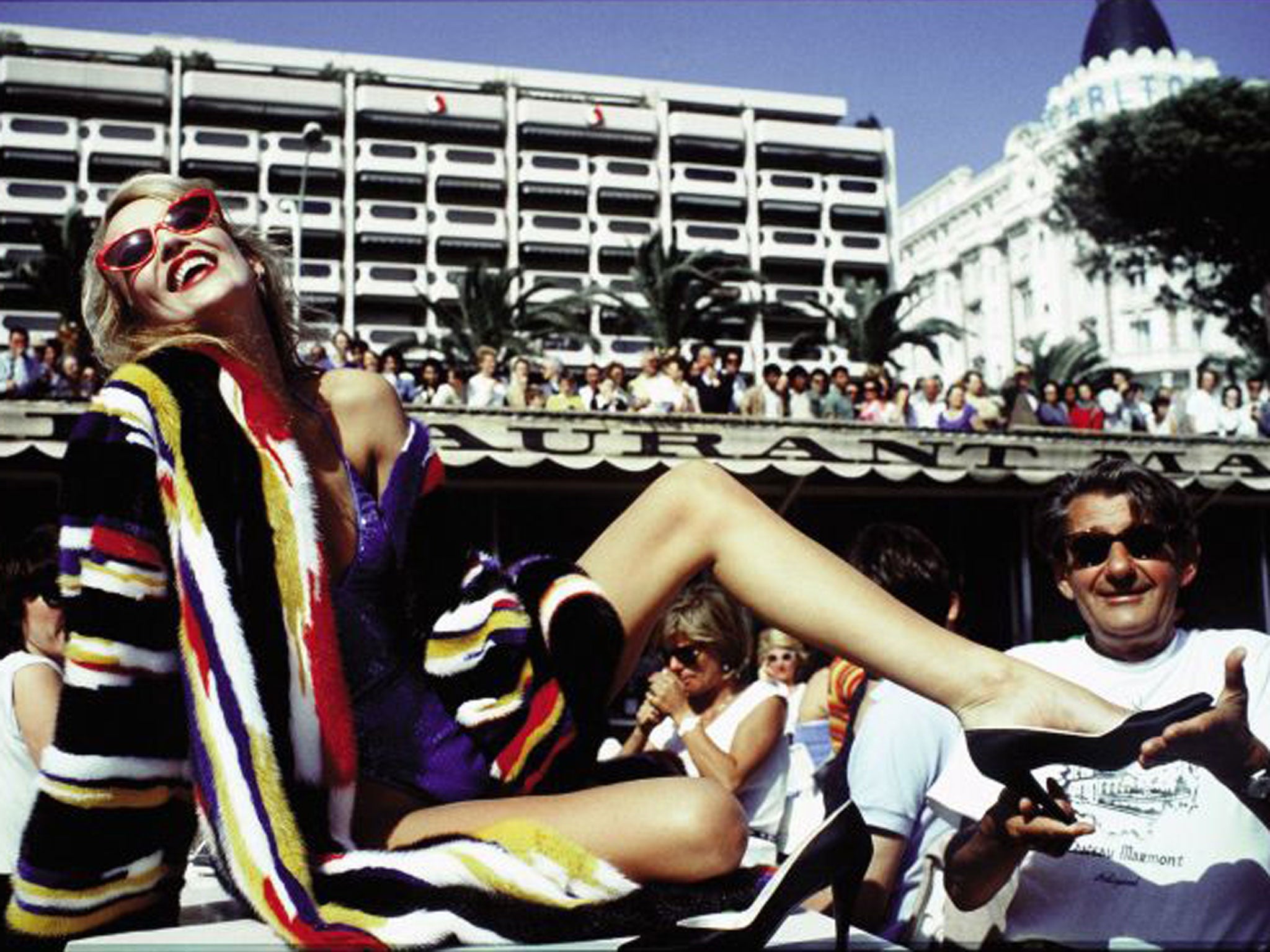

But the rest of the world saw Bailey. His relationships – with Jean Shrimpton (the face of the Sixties), Catherine Deneuve (France’s first lady of film) and Marie Helvin (every schoolboy’s dream in the Seventies ) – were front-page news while he himself inspired Antonioni’s landmark film, Blow-Up.

Considering that Bailey has not only photographed the truly iconic but, is an icon himself, one wonders why this exhibition hasn’t happened before? “You’ll have to ask all those scholarly fools!” He snarls. “They overlook and marginalise photography.”

“But it is not a retrospective,” he stresses. “It’s in no order whatsoever and it’s not about looking back. I’m still working flat out. I’ve got a lot of work left in me.”

And looking at the man – a veritable bundle of combustible energy – I could not agree more.

Bailey’s Stardust, National Portrait Gallery, London WC2 (020-7766 7331) to 1 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks