The plot thickens... Why are British novels becoming less emotional, and US ones more so?

John Walsh discovers a whole new chapter of scientific research

Do American writers express more emotion than their British counterparts? A scientific paper, just published, has concluded that Stateside writers are champions at emotional incontinence, streets ahead of glacial, buttoned-up, clenched-buttock Limeys.

The Expression of Emotions in 20th Century Books, is the promising title of the study by four academics at Bristol, Stockholm, Sheffield and Durham universities. The quartet reached their conclusion by taking a number of “mood-words”, expressive of strong feelings, in six categories – Anger, Disgust, Fear, Joy, Sadness and Surprise – and seeing how often they appeared in “roughly 4 per cent of all books published” between 1900 and 2008.

This is a head-spinningly vast area of enquiry, a Pacific Ocean of books and words, from which the authors dredged up some intriguing generalisations.

The high or low incidence of certain “mood words” (like Joy or Sadness) during the 20th century meant the authors could distinguish “happy” or “sad” periods and plot a graph of historic trends: they can tell us the century started miserably (death of Queen Victoria,) rose to a high point in the 1920s (jazz and flappers) and plummeted to a nadir in the early 1940s (war, Blitz, rationing) before climbing back to a period of stability in the 1960s. But we knew that. More interesting is the finding that, since the 1960s, American books have increased their “mood content” by comparison with the Brits. You can guess why, can’t you? Words expressive of personal ego (“independent,” “individual,” “self”, “solitary,” “personal”) increased while words that evoke community (“team”, “village,” “group,” “union”) declined. Egocentric phrases like “I get what I want,” or “It’s all about me” galloped off in US writing, while old-fashioned communal sentiments (“united we stand”) languished unwanted. The egomania of 1970s America right to the end of the century and now shows up in this research, a trend discernible from space.

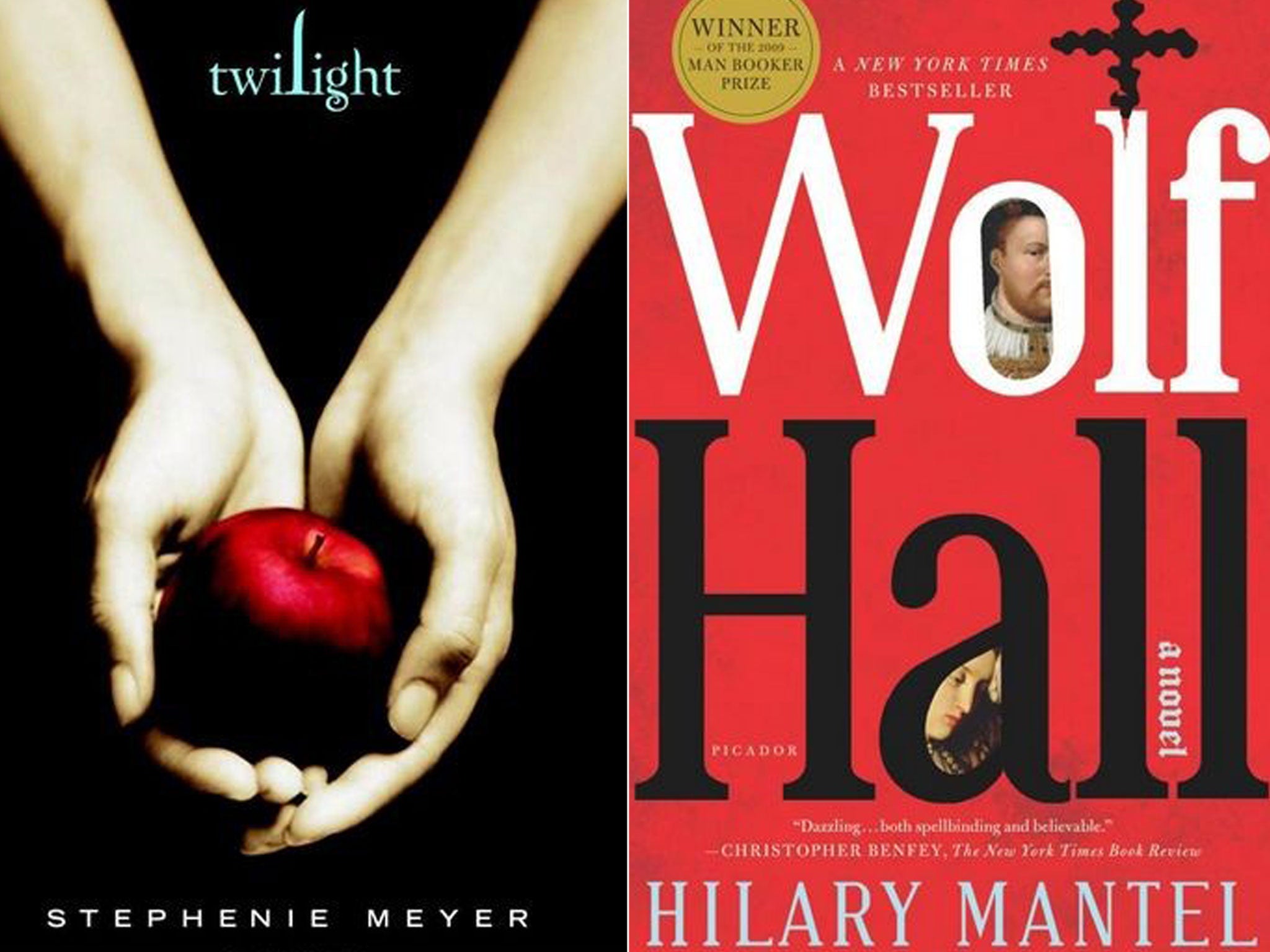

Should we worry about expressing less emotion in novels than our American friends, as a subset of the research implies? Shall we try harder? Must we strive to emulate the palpitations of Stephenie (Twilight) Meyer, the frantic onomatopoeic mugging of Tom (“Me Decade”) Wolfe, the grand guignol extremism of Stephen (The Shining) King and the bogus, oo-er mysticism of Dan (Da Vinci) Brown?

Did you see this research, Ms Mantel and Mr McEwan? Just knock it off with the perfectly judged prose and the elegant cadencing, will you, and give us some flipping emotion, okay?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks