How the Maastricht Treaty sowed the seeds of discontent that led to Brexit

In the third of our five-part series on Britain’s often reluctant role on the European stage, Andrew Grice explains how the unravelling of Sir John Major’s initial victory created a political shift 23 years in the making

Rarely in British politics has triumph turned so quickly to disaster. Sir John Major was hailed as a conquering hero by Eurosceptic MPs and newspapers for winning crucial opt-outs for the UK when European leaders took a decisive step towards political union in December 1991.

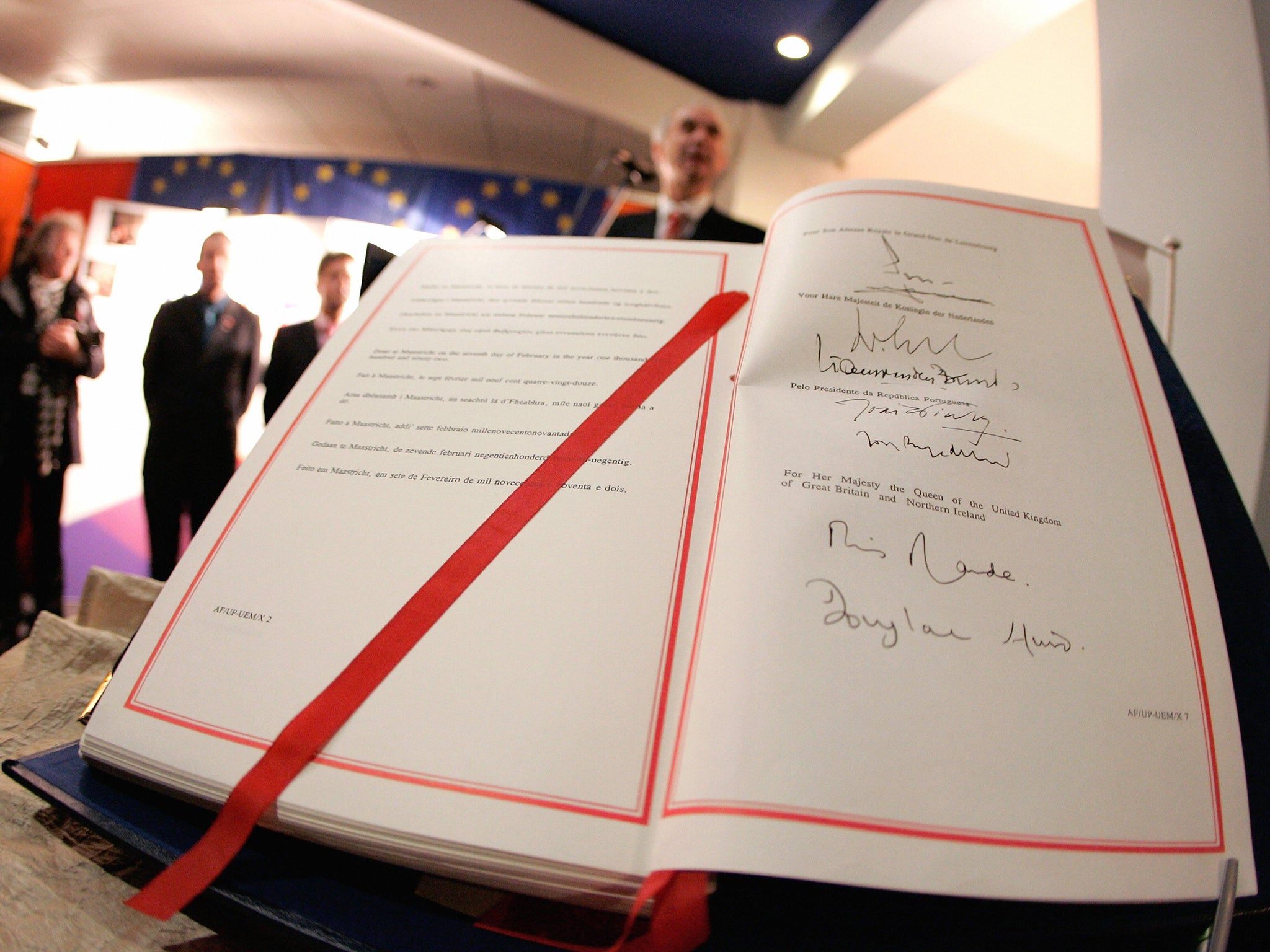

Their summit in the Dutch city of Maastricht was a landmark one for both Britain and the rest of Europe. The 12 leaders at the time agreed to turn the European Community into the European Union, whose powerful symbol would be a single currency. But the integrationist leap forward risked leaving Britain in the slow lane, and arguably sowed the seeds for the 2016 referendum decision to leave the bloc.

I was at the summit, and can attest that Sir John’s triumph was not the usual spin by a national leader to his domestic audience. The mild-mannered Tory prime minister never actually uttered the words “game, set and match” attributed to him by me and the other journalists in Maastricht. They came from one of his aides. Characteristically, Sir John merely called the outcome “very satisfactory”.

He had to threaten the nuclear option of vetoing the entire Maastricht Treaty unless the UK secured an opt-out from the single currency. Although he had promised to keep Britain “at the very heart of Europe” after succeeding the more Eurosceptic Margaret Thatcher in 1990, Sir John was no federalist. While he believed economic and monetary union (EMU) was inevitable one day, he thought it premature given the economic disparities between EU states, but wanted the UK to be free to join at a later date. His fellow EU leaders grudgingly accepted.

But Sir John had another problem with the draft treaty: the social chapter of workers’ rights, which he believed would undermine the UK’s competitive advantages. He knew that Michael Howard, his employment secretary, might resign if he signed up to it. In late night negotiations, Sir John didn’t blink first, and other leaders conceded a second UK opt-out on the social chapter.

He had a hero’s welcome when he reported back to the Commons. If Boris Johnson had won such a deal, he would have claimed he had managed to “have cake and eat it”. As well as the two opt-outs, the EU would not take control of immigration, defence, education and the F-word – federalism – was left out of the treaty. The UK prevented a rupture with its EU partners who, as David Cameron would discover when he used the veto in 2011, would have gone ahead without Britain if necessary.

However, the new EU blueprint did contain some ammunition for the Eurosceptics who would soon turn against Sir John with a vengeance: an increase in majority voting in the council of ministers, more powers for the European parliament and EU citizenship. Critics warned the intergovernmental co-operation on foreign and security policy and on justice and home affairs would lead to demands for ever closer union in these areas.

Sir John unexpectedly won a fourth successive general election victory for the Tories in April 1992. But then events outside his control turned his Maastricht success to dust. In June 1992, the people of Denmark voted against the treaty in a referendum. It put a spring in the Eurosceptics’ step. Sir John had to pick up the pieces as the UK took over the EU’s rotating presidency.

Then in September, Britain suffered a humiliating ejection from the European exchange rate mechanism (ERM). Black Wednesday was a day of chaos as interest rates were hiked to 15 per cent. According to some officials, Sir John drafted a resignation letter, but was talked out of quitting. He denied having a “wobble”. Whatever the truth, his authority as prime minister, and his government’s reputation on the economy, did not recover.

The 1992 election had cut the government’s majority to 21. There were more than 21 Tories who opposed Maastricht, giving the government a headache because parliament had to approve the treaty. After more than 200 hours of Commons debate and over Communities (Amendment) Bill, Sir John defeated a Tory rebellion with the help of opposition MPs. His problems were not over. Labour had a “ticking time bomb”: an amendment forcing a vote on the social chapter before the treaty took effect. This created what Sir John called a “mad hatter coalition” of Labour, who backed the charter, and Tory Eurosceptics, who opposed the treaty.

Amid dramatic scenes, the first vote was tied 317-317, the government surviving it with a casting vote in favour of the status quo by the speaker Betty Boothroyd. But it lost the second by eight votes.

Sir John immediately announced a vote of confidence in the government the following day. It was a gamble; defeat would have meant an election, and the likely end of his premiership. The Eurosceptics blinked, and he won by 38 votes. Their retreat had consequences when Theresa May put her Brexit deal to the Commons 25 years later. One veteran Europhobe recalls: “We caved in on Maastricht. It was a mistake. We learnt a lesson: never again.”

The trench warfare did not end when the treaty was ratified. Bitter Tory divisions on Europe only deepened

The trench warfare did not end when the treaty was ratified. Bitter Tory divisions on Europe only deepened. Nine Tory MPs lost the whip, depriving the government of its majority, but became martyrs and were later restored to the party fold. Sir John was repeatedly caught in the crossfire of a Tory civil war; he sent signals to the rival camps he was on their side, but disappointed both. As Kenneth Clarke, the Europhile cabinet minister, later recalled, disagreements about Maastricht “dominated the 1992-97 parliament in a totally destructive way”, even though the details were “obscure” and “daft”.

It is worth noting that Tory Eurosceptics wanted to halt moves towards a federal EU rather than take Britain out. The early pressure to leave came from outside the party. Sir James Goldsmith’s Referendum Party was a forerunner for Nigel Farage’s Ukip. But Norman Lamont, sacked as Sir John’s chancellor, raised eyebrows in 1994 when he became the first senior Tory to suggest that withdrawal was not unthinkable. A seed had been planted.

Many of the prime minister’s opponents wanted to force him out of office. Their rebellion against Maastricht was stoked by Lady Thatcher, even though Sir John was convinced she would have signed it if she had still been in office. In the Eurosceptics’ eyes, Sir John was a weak successor who betrayed her legacy after she had been deposed by Europhile cabinet ministers for standing up to the EU.

The Major cabinet was divided. He famously referred, in off-camera but recorded remarks, to Eurosceptic ministers as “bastards”, who the media took to mean John Redwood, Michael Portillo and Peter Lilley. He accused his critics of “dripping poison” about him to an increasingly anti-European press, which lapped it up. Stinging criticism of the prime minister was low hanging fruit for Westminster journalists. As one of my colleagues at the time now remembers: “We didn’t even have to ring ministers. They rang us.” The disloyalty, leaks and breakdown of cabinet discipline would be repeated when Ms May tried to push through her Brexit deal.

Sir John limped on. His woes were made worse by the election of Tony Blair as Labour leader in 1994. His wounding Commons jibe — “I lead my party, you follow yours”— epitomised the Major premiership.

It couldn’t go on. Sir John brought matters to a head in 1995, resigning as Tory leader and challenging his enemies to “put up or shut up”. Sir John Redwood stood against him on a “no change, no chance” platform. The prime minister won the votes of 218 Tory MPs to Sir John Redwood’s 89, but it was hardly a ringing vote of confidence. The die for his time in office was cast on Black Wednesday, almost five years before the Tories suffered a crushing defeat at New Labour’s hands in 1997.

Looking back on Maastricht through a longer lens, it was a summit which Sir John could claim offered the UK the best of both worlds but ended up delivering the worst. While the rest of the EU embarked on an ever closer union, the UK opted out. It did the same on the Schengen “open borders” agreement. Arguably, this was the start of a process that ended in the 2016 referendum. The UK was not at the “very heart of Europe”; perhaps it was always half-hearted about membership. Maastricht was the moment when, by keeping out of the EU’s central project of the euro, the UK was destined never to achieve the goal of becoming the third part of the Franco-German engine that drives the Union. Indeed, some Tory pro-Europeans do not view Maastricht as a diplomatic triumph. “All we did was to say ‘no’ to everything; that weakened our influence later,” said one former cabinet minister.

Sir John insists he was being pragmatic, not least because the British economy or public opinion was not ready for single currency membership. In his memoirs, he noted that the demands for political union agreed in Maastricht had been fuelled by Lady Thatcher’s success in securing the European single market in goods and services in 1986.

Sir John said: “She conceded the most dramatic advance of decision making by majority voting … since the community was launched. The Single European Act whetted the continental appetite for communal decision making and fed the ambitions of the commission. It gave force to the argument that a single currency was needed in the single market, and strengthened the case for further harmonisation of policy. The wind was in the sails of the federalists.”

That Lady Thatcher unwittingly paved the way for the ever closer union she so strongly opposed is one of many ironies as the UK’s 47-year EU membership ends.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks