Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris review: A fascinating show reveals John’s radical side

This Pallant House Gallery show makes the unusual case for Welsh painter Gwen John as a social butterfly, but she pursued loneliness in her art

Gwen John’s searching portraits and poignant life story have featured surprisingly little in the recent surge of interest in neglected women artists. And that may be because she’s hardly considered neglected. The Welsh painter (1876-1939) was a key figure for the 1980s wave of pioneering feminist art criticism, the subject of a major biography and even a BBC drama series called, tellingly, Journey Into the Shadows. John then was seen as a fragile figure bravely holding her own between two bombastic male egos. On the one hand there was her brother, the once stellar portrait painter Augustus John, on the other her longstanding lover, the great French sculptor Auguste Rodin.

John’s modestly scaled and unflinchingly frank portraits and interiors were a revelation then. But now Augustus is a near-forgotten figure and Rodin just another dead, white man; the fact that an unassuming Welsh woman was a more truthful, more modern – and, perhaps simply better – artist than either, doesn’t feel so much of a story.

This exhibition, however, curated by Alicia Foster, author of a new biography of John, is out to rescue the artist from the forlorn waif image. Far from living a life of tragic isolation, as has tended to be supposed, John, the show argues, was very much in contact with the major currents of “the most exciting times and places in the story of European art”. She met Picasso and Matisse, was close friends with the German poet Rilke, became the model and muse of the great London-based American painter James McNeill Whistler and enjoyed numerous same-sex relationships, as well as a decades-long liaison with the most famous sculptor in the world, Rodin. Far from wasting wanly away in her room, this newly discovered Gwen John was socially gregarious and enjoyed strenuous walking holidays.

Yet the first painting we see seems to confirm everything embodied in what the show dismisses as “the myth of Gwen John”. Girl in Blue (1910-20s) is executed in colours so muted and similar in tone, the painting appears about to dissolve before our eyes, and while the subject’s expression isn’t actively unhappy, the abiding impression is of a certain mournfulness.

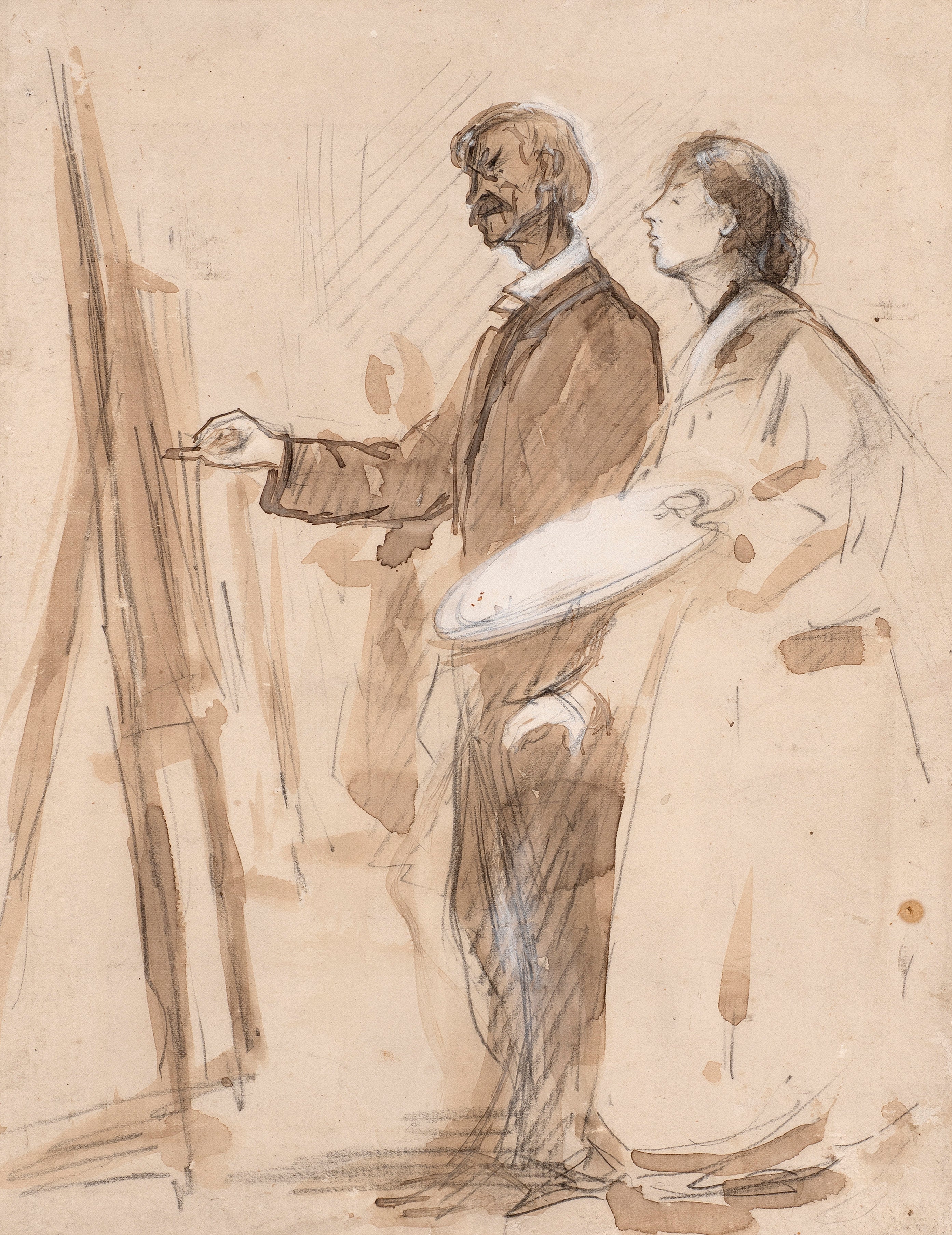

But we don’t have the chance to stick with and assess this quintessential John mood, as the show develops into a brisk stroll through her times, with works from just about every artist she had any connection with, including a lovely Cezanne study of a boy’s head and a truly hallucinatory view of the backstreets of Dieppe by Walter Sickert. There are numerous life drawings by fellow students at London’s Slade School of Art – though none, frustratingly, by John herself. And there are works by artists she had only the most tangential links to, including the currently fashionable German Expressionist Paula Modersohn-Becker, who she may conceivably have met, and the Danish painter of slightly surreal interiors Vilhelm Hammershoi, who she may conceivably have heard of. Some of these tenuous connections are, however, revealing. John’s early bedsitter paintings, created after her move to Paris in 1904 – with pensive figures silhouetted against strong external light, are vastly more convincing than Hammershoi’s popular but very mannered images in the same vein.

Her portrait of Dorelia McNeill (1903-4), her brother Augustus’s life-long partner, knocks the socks off his horribly slick painting of her. As with many of John’s best images, the subject’s natural, unaffected expression makes her feel disconcertingly modern, rather than a historic figure from over a century ago.

Yet the many works by her friends and associates, in which John appears as a naked or clothed model compound the sense of her as an elusive, strangely insubstantial figure. In vigorous drawings by Rodin for which she may possibly have modelled, her head – if it is hers – is a mere cursory squiggle.

When we finally get to see a critical mass of John’s paintings in her Convalescent series of portraits (late-1910s to mid-1920s), they’re shown, tellingly, beside a painting by the great French “Intimiste” Edouard Vuillard, of whom she was well aware. Where his “modern” interiors are filled with the everyday clutter of family life, the backgrounds to John’s paintings become starker and emptier – and her entire approach more minimal – as her career progresses.

Completed over a 10-year period, John’s four Convalescent paintings show the same long-haired young woman, her appearance barely changing, as she sits reading against a blotchily painted greyish background. Yet far from feeling samey, the paintings draw you in with the relatively small differences from image to image, the slight variations in the quality of the light and the pressure of John’s brush on the canvas seeming to become bigger and more significant the longer you keep looking.

The wall texts argue that these paintings are informed by John’s burgeoning Catholic faith (she converted formally in 1913), and that the convalescence of the title symbolises France’s physical and spiritual recovery after the First World War. Yet these paintings’ spirituality seems of an abstract, almost Zen-like order, embodied in the relentless pursuit of the truth of a single image over years of effort, rather than in “Christian” imagery. It’s an approach that brings to mind modern artists as diverse as Cezanne (one of John’s great inspirations) and Mark Rothko.

Four paintings of Benedictine nuns confirm the sense that John’s work isn’t always quite what it seems. While two of the large portraits were painted from life, the others – representing the order’s 17th-century founder – were mugged up from a tiny engraving shown in an adjacent display case, though you’d hardly notice the difference at a glance. With their small heads and very large bodies – a characteristic of many of John’s paintings – the whole lot of them are pretty strange works.

John emerges from this fascinating show as a much odder, more interesting and more radical artist than I’d imagined. Various drawings and watercolours dotted through the exhibition testify to the fact that she was barely capable of putting down a mark that wasn’t entirely honest and in some way graceful. But as a person she feels no less an enigma. Much of her painting was done when she was living in one room in Paris, and even when she had made money and moved to more spacious premises, her work retained a dogged, monastic, “bedsitter” quality. In real life, Gwen John may have been as gregarious, even boisterous, as the exhibition maintains, but in her art she seems to have chosen loneliness as a conscious aesthetic path.

Pallant House Gallery, until 8 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks