Spirited Away: The nightmarish fantasy that brought Studio Ghibli to the west

Hayao Miyazaki’s movie stuck out like a sore thumb when it was screened at Berlin Film Festival two decades ago but the Japanese animation went on to become widely adored by western audiences. Geoffrey Macnab looks at how it challenged entrenched prejudices and ended up being such a hit

You could sense the embarrassment among the PR team representing Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away when it screened at the Berlin Film Festival almost exactly 20 years ago this week. Here was a Japanese animated feature aimed (it seemed) primarily at a children’s audience. The film, made through Miyazaki’s company Studio Ghibli, had been a runaway box office success in Japan the previous summer but journalists and distributors still didn’t expect to see it in the main Berlin competition.

The programme was packed that year with heavyweight new art house films from revered directors such as Costa-Gavras, Paul Greengrass, Marc Forster and Bertrand Tavernier. What place did Miyazaki’s story about a little girl separated from her parents in a disused theme park have next to Bloody Sunday, Amen and Monster’s Ball? The initial impression was that the Berlin organisers were pulling some kind of cheap stunt. Self-important critics were in no hurry to review a kids’ cartoon. The film, though, went on to win the festival’s biggest award, The Golden Bear.

These days, Miyazaki is revered in the west as well as in Asia. However, two decades ago, the situation was very different. Then in his early sixties, Miyazaki (born in 1941) was already a huge name in Japanese animation before Spirited Away but his films hadn’t yet caught on in cinemas internationally. There had been high hopes in the US for his 1997 feature, Princess Mononoke, which Miramax, then a subsidiary of Disney, had released but box office figures had been disappointing – and the Studio Ghibli staff were left bitterly disappointed at the way their work was treated by Harvey Weinstein and associates.

Back in early 2002, if you mentioned Japanese animation to critics in Europe and the US, most would think immediately of violent Manga. Few had any idea about the visionary movies that Miyazaki had been making for many years. So how was Spirited Away able to challenge and change all their entrenched prejudices?

The answer is simple. The moment you start watching a Miyazaki film, you realise that you are in the presence of something truly special. The colours are startling. The wit and humour are arresting. He takes a child’s eye view of the world and yet his films never turn syrupy. They can scare as well as delight you. They combine surrealism and grotesquerie with extreme tenderness. His work is very Japanese in style but also draws on western literature. He is a big fan of Ursula Le Guin and Little Prince author, Antoine de Saint-Exupery. In Spirited Away, you can also see traces of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass.

Miyazaki has acknowledged his admiration for Disney films such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Fantasia and Pinocchio but, as he told one interviewer, “their depiction of the inner thoughts of human beings was so simplistic that I didn’t enjoy them very much”. It’s a very revealing observation and hints at why, eventually, western adults as well as kids became so enamoured of his work. In Miyazaki’s films, the inner thoughts are always paramount.

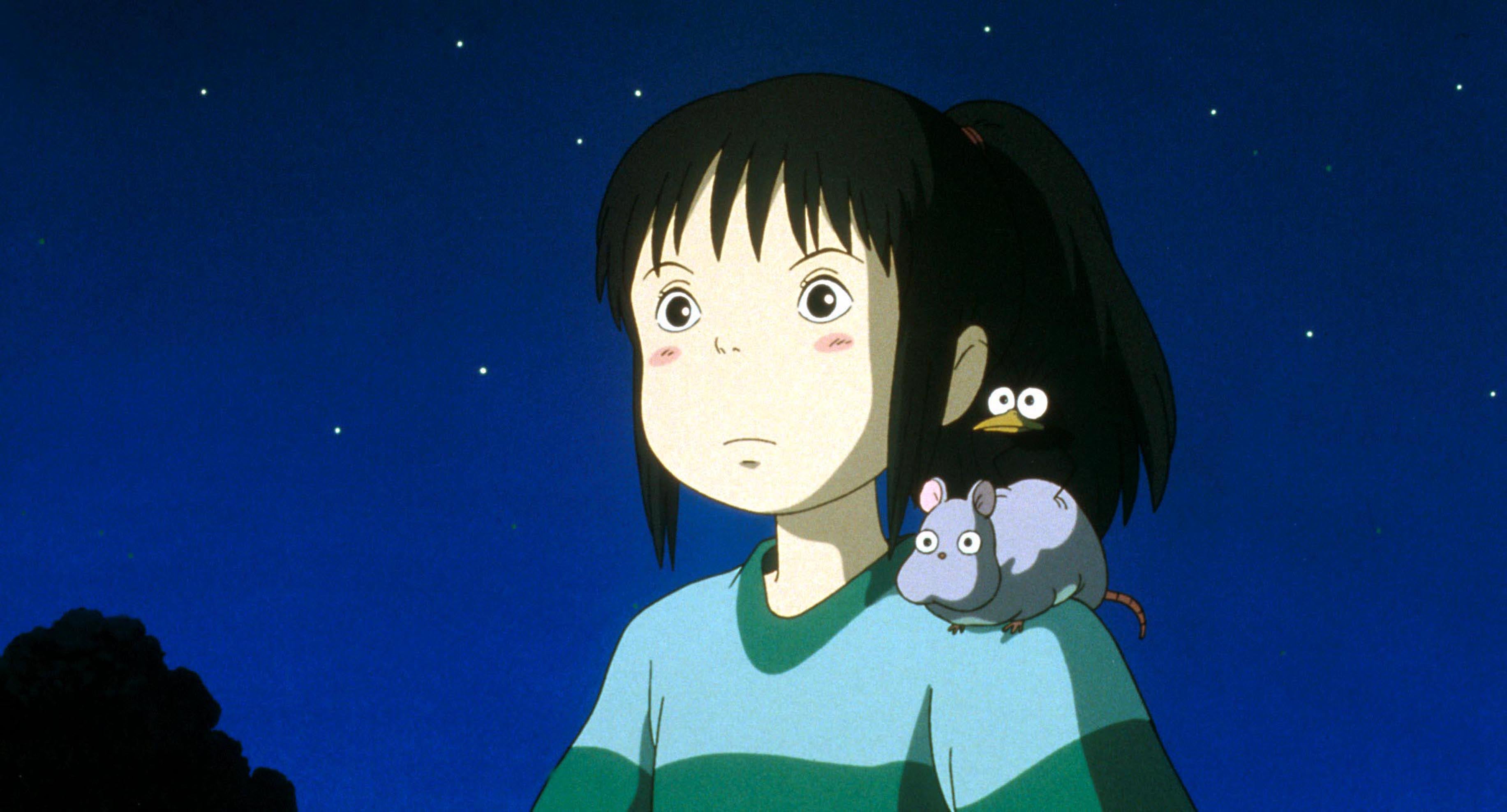

Spirited Away revolves around a 10-year-old girl, Chihiro Ogino (aka Sen). First seen in the back of her parents’ car, she is a young brat, unhappy at having to move home and beginning to question her parents’ authority. On their way to the new house, the father takes a short cut, gets lost and ends up in what appears to be an abandoned theme park. He and his wife discover delicious food that has been left out on a stand. There is no one there to take payment but they guzzle it anyway. Watching them eat, Chihiro is amazed to see them turn into pigs. She herself then becomes lost in a strange dreamlike world that is both enchanting and often very threatening. Like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, she needs to find her way home.

Miyazaki has few equals when it comes to depicting fantasy worlds on screen. Spirited Away is full of eccentric but deadly creatures who can always tell when there is a human in their presence. The film is both funny and lyrical. It has many magical scenes, for example the eerie early moment in which Chihiro seems to be turning into air. Only when her mysterious friend Haku gives her something to eat does she recover her physical identity. Poor little Chihiro has all sorts of phantasmagoric and nightmarish experiences. Yubaba, the hideous, bejewelled witch who runs the bathhouse, threatens to turn her into a lump of coal or a piglet or, worst of all, to steal her name. Others discuss frying or boiling her.

Like the best fantasies, Spirited Away can be interpreted in many ways. It’s a coming-of-age story in which Miyazaki shows an uncanny ability to get inside his young protagonist’s head. It’s an adventure and it can even be read as an ecological fable. The exquisite artistry and thematic richness notwithstanding, the film would probably have shared the same fate in the west as Princess Mononoke if it hadn’t been for the Berlin triumph.

Arguably, the single figure most responsible for Miyazaki’s popularity in the west today is French producer Vincent Maraval from the maverick company Wild Bunch (the outfit behind such confrontational films as Fernando Meirelles’ City of God and Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible). He had been told about Miyazaki (this unknown “genius of animation”) by a colleague at StudioCanal, the company where he previously worked. Maraval watched the films. “I was amazed,” he tells me.

On a work trip to Japan, Maraval asked to meet with Studio Ghibli. “I went to see them many times,” the French executive recalls of how he gradually built up a relationship with the Japanese company that, after its unhappy Weinstein experience, was very wary about working with westerners. He learned quickly that Miyazaki and his staff were fiercely protective of their brand. They weren’t interested in short-term profit. They wanted their films to be shown in cinemas again and again to new generations – and they wouldn’t allow foreign distributors to re-edit, re-score or tweak them in any way. To counter piracy, they stopped their work from being broadcast in too high a resolution on TV or on video.

In late December 2001, Maraval realised that Miyazaki might be prepared to enter Spirited Away into the Berlin competition two months later. The Japanese director had had a dispiriting experience in Berlin in 1998 with Princess Mononoke (which had screened out of competition to indifferent audiences) but, with Wild Bunch to back him, he was ready to try again.

By then, though, the deadline for submitting films had already passed. “At that time, we had no contract. It was the beginning of a relationship,” Maraval recalls of how he started his work with Studio Ghibli. “We called Berlin, I spoke to Beki Probst [the Berlin market director] and told her she should watch the film, it is a masterpiece.”

Probst watched the film and immediately agreed. It was allowed into the competition. There was, though, still widescreen scepticism among critics and distributors to overcome. UK distributor Will Clarke remembers seeing the film in a near empty theatre in Berlin. “There were only two other people in there,” Clarke says. He kept on pinching himself. This was the best movie had seen in many months, if not years, and yet no one was paying attention to it. “The impact was huge on me, absolutely huge. It’s just pure cinema, isn’t it… Miyazaki is a genius at creating these unusual worlds and bringing them to life.”

The moment the screening finished, he rushed to Wild Bunch to persuade Maraval to sell the film to him. “I actually ran to their office.” At the time, his company Optimum Releasing was not a major player in UK distribution. He paid more than the company could then really afford. It helped his cause that no other UK companies seemed to be after it.

Spirited Away eventually made a fortune for Optimum, selling 750,000 copies on DVD alone. In the cinemas, Clarke arranged for the dubbed version to be shown during daytime so that kids could watch it, and for the original version to be screened with subtitles to adult audiences in the evenings. He also began buying rights to Miyazaki’s older films and set up a Studio Ghibli label.

Now, the more Spirited Away is shown, the more people want to see it. Since it has become available on Netflix, DVD sales have gone up, not down, and it has also continued to be screened in cinemas.

Maraval has produced and executive produced more than 60 films with directors from Ken Loach to Steven Soderbergh, from Sean Penn to Nicolas Winding Refn. It is clear, though, that Spirited Away moves him as much today as when he first saw it.

“I have seen Spirited Away 15 times and I am still crying at the same sequences… I think it is a mix of poetry, humanity, ecology and fantasy. For me, Miyakazi is one of the top artists of our time,” Maraval says of the Japanese filmmaker, who might have remained an unknown treasure to most western viewers if he himself hadn’t smuggled Spirited Away into the Berlin Festival by the back door all those years ago.

‘Spirited Away’ is available on Netflix

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks