The working class have always produced ‘high’ culture – the middle classes just stole it

Whether it was writing great plays, poetry or creating musical masterpieces and art, it’s time to recognise and revive the rich culture of ‘ordinary’ people, says Richard Benson. Together with Michael Sheen, he has launched a magazine to showcase working-class writers

One day in the 1940s, a young housemaid called Margaret Powell approached her employer, Lady Downall, to ask if she could borrow a book from the library of her Chelsea residence. The good lady visibly blanched.

“Of course, certainly you can, Margaret,” she said. “But I didn’t know you… read.”

When the maid shyly chose the first volume of In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust to read, it was a portent.

In the 1960s Margaret Powell, who had grown up in poverty, herself became a bestselling memoirist. Her book Below Stairs inspired the classic BBC drama Upstairs, Downstairs in the Seventies, and in the 2010s it was Julian Fellowes’ source material for Downton Abbey.

Never heard of her? Well, that’s not surprising. Downton was quality, literary-ish television, and despite touting egalitarian credentials, today’s critics don’t generally associate the working classes with that sort of thing. Remember the Booker Prize Foundation director Gaby Wood laughing at the book club in Scunthorpe in 2022 because it had “a steel worker and a dinner lady” among its members?

For the likes, there are the soaps, quiz shows and Foxy Bingo ads; as the artist Grayson Perry, brought up in a working-class household in Essex, says, these days you can’t be seen as appreciating culture unless you have a certain level of “education”.

It’s a typical paradox of our lip-service-paying times: creative industries proclaim their “openness”, and yet the proportion of people in the arts from working-class backgrounds has fallen to literally half of what it was in 1970. Young working-class adults are four times less likely to work in the creative industries than their middle-class peers. Top-selling musicians are now more than six times more likely to be privately educated than the general public.

And yet from Flora Thompson and Irvine Welsh to Hilary Mantel and Sam Selvon, from Charles Rennie MacKintosh and LS Lowry to the Ashington Group and Steve McQueen, from Thomas Chatterton and Lennon & McCartney to Meera Syal and Michael Clark and Richard Burton, all showcase how artistic disciplines have always been practised in British working-class areas.

In the South Yorkshire mining community I grew up in, there was a local literary heritage that included writers like Ted Hughes, Barry Hines and David Storey, and contemporaries such as Joanne Harris, Ian McMillan and, just a bit further away, Caryl Phillips and Simon Armitage. Musically, there was Sheffield, whose bands from The Human League to Pulp to the Arctic Monkeys have been as innovative as Manchester’s. As for artists, we knew that Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and David Hockney, all had come from humble backgrounds. I’m not saying people sat around discussing modernist sculpture in the pubs, but plenty of ordinary folk knew who they were and took an interest in the work.

And yet entire disciplines in these worlds have, as Grayson Perry has observed, been “colonised” by the middle classes. Selina Todd, professor of Modern History at Oxford University, has pointed out that Shelagh Delaney’s A Taste of Honey “would probably never be performed” if she wrote it today. “In many ways, the arts have become more elitist since the Fifties.”

The working-class author Pat Barker believes it has become “easier for women, but harder for the working class” when it comes to publishing novels. “It’s the under-representation of the working class that really needs looking at. We’ve split off into little identity groups – women, gay people, trans people, various ethnic minorities. And what you need to see is that a lot of these people are working class, and it’s the working class that are under-represented.”

One infuriating thing about this is that despite including successful writers and artists, the working class – the dinner ladies, steel workers and the rest – is spoken of as if it’s not even interested in art and culture. This is so patently untrue it could be argued only by people who substitute stereotypical images for actual experience.

In many working-class homes with memories spanning multiple generations, the idea is laughable. It’s not just about people knowing a few famous local working-class artists who made it either. There was – still is – a grassroots creativity and self-expression, although people wouldn’t necessarily use those words.

My grandad, a miner and lorry driver, was a self-taught jazz drummer who played in clubs (family legend: he once backed Liz Dawn, who played Vera Duckworth on Coronation Street, when she was a singer).

As a teenager, my cousin Gary, who would go on to be a ventilation engineer, somehow worked out that the superhero comics he loved were based on Greek myths, and persuaded his library to get him a copy of The Odyssey. Above the bar in our nearest working men’s club is a large, beautiful black and white mural commemorating the 1984–5 miners’ strike; it was by a local painter and decorator.

Growing up in my village there were dance schools, art classes, marching bands, folk clubs, jazz, rock and brass bands, tribute acts, drag queens and northern soul nights, and elocution classes that taught kids to recite poems without their Barnsley twang (my aunty Lynda still does a Walter de la Mare on occasion). If all that seems a bit basic and parochial, that wasn’t always the spirit of the participants.

Take brass bands: they are pigeonholed for doughty traditionalism, but in several cases this reputation obscures serious artistic ambition. The Grimethorpe Colliery Band might be famous for inspiring Brassed Off, for example, but less famously it commissioned its own avant-garde pieces from composers such as Harrison Birtwistle.

If you think any of this was rare rather than typical, then you have swallowed an idea peddled by politicians of both major parties since the 1980s. The idea is that wanting better material conditions – nicer houses, clothes, cars, whatever – means you want more middle-class behaviours and culture. Its implication is that the working class has no culture, and no urge to self-improvement. Yet you need only turn on the television and watch the brilliant work of Bafta winner Sophie Willan, Stephen Graham, or filmmaker Shane Meadows, and playwright James Graham and, further back, to Harold Pinter or Arnold Wesker to realise how baseless that claim really is.

If you’re looking for the antidote to the relentless vilification of working-class culture, you need Jonathan Rose’s masterful 2002 book The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes, which painstakingly documents the self-education and artistic endeavours of ordinary Brits since the industrial revolution.

It’s true that this industrial culture began to recede under the attack from Mrs Thatcher’s government in the 1980s, but it is far from dead. Not for nothing did the artist Jeremy Deller create an image showing the relationship between brass bands and acid house, or Oasis drop references to their Burnage childhoods, or Ayub Khan-Din document the intersection of race and class in East is East.

We’re publishing stories and photographs documenting the whole spectrum of 2020s working-class culture. The response has been incredible

Since the 2000s, apart from grime and pockets of other musical creativity, that class consciousness has faded as the arts have been professionalised and colonised by the middle and upper classes. Increasingly, working-class kids are shut out by nepotism, the inability to take low-paying entry-level jobs, and to pay for courses that are now needed for professional qualifications. A new set of barriers has been put in place.

Reading the Rose book, you realise that we have been here before. The enjoyment of the arts has been seen as a way of improving lives, and when the universal education acts of the 19th century made everyone literate, the working class read voraciously. The dominant class of intellectuals loathed that new mass readership, who they felt had lower standards and insufficient respect, and set about trying to distance their work, parodying the self-educated; this is why T. S. Eliot uses Greek with no translation in The Waste Land, and E. M. Forster created his hapless, culture-loving clerk Leonard Bast in Howards End.

As a result, we have “literary” books and the mass market. In a way, the same old fault line is being reopened. If you take Jonathan Rose’s book out in public, I have found, a strange thing happens. Someone will notice the title The Intellectual Life of the British Working Classes and say something like, “That must be a short book.” Then you will get talking, and they will tell you a personal story about someone they knew who loved art or books or music, and changed their lives through it.

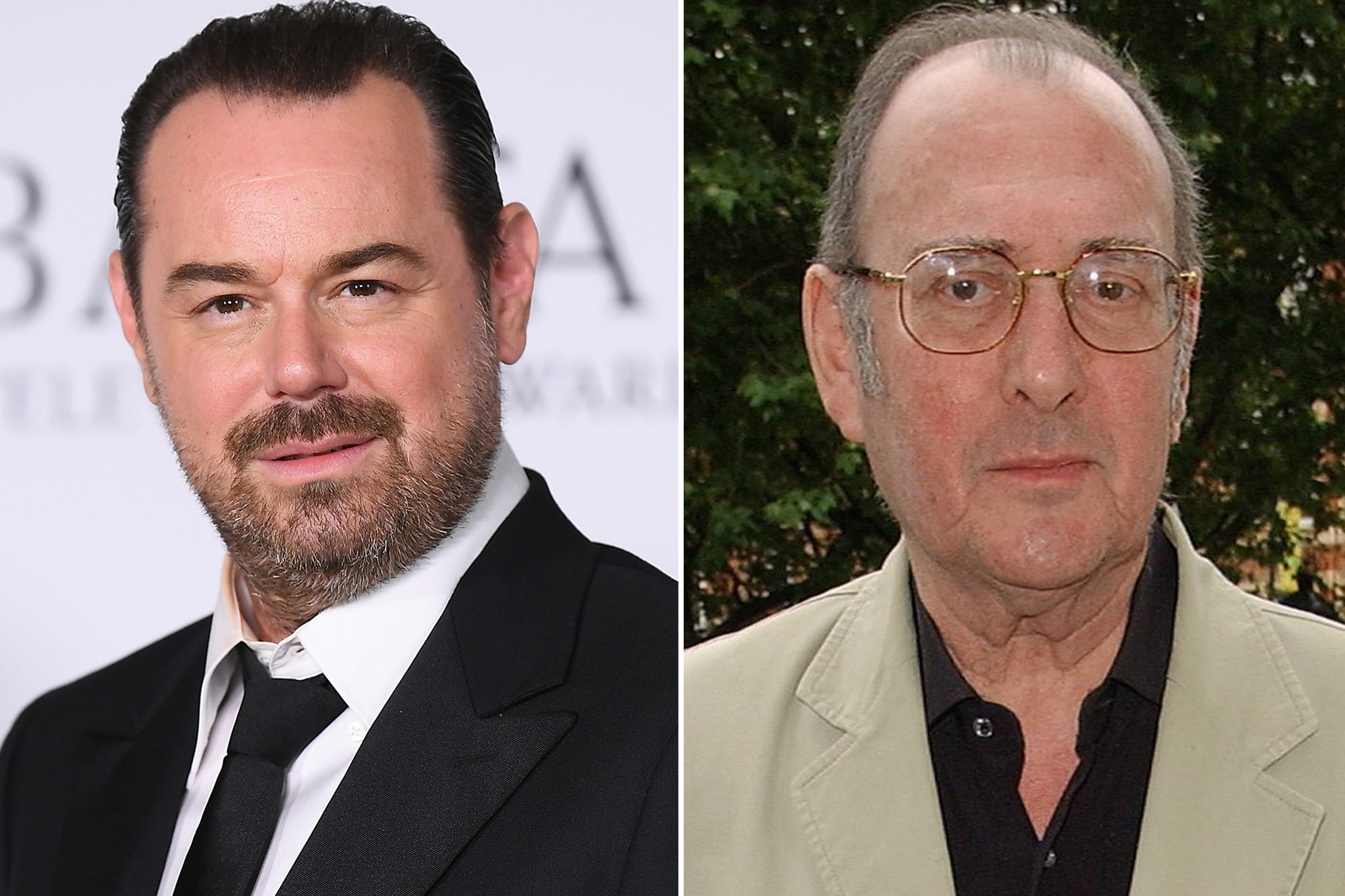

Earlier this month the actor Danny Dyer eloquently described on Desert Island Discs how a drama teacher’s encouragement changed his life. Shunned by middle-class peers in the theatre, he had his confidence boosted when Harold Pinter took him under his wing. And yet he still had to endure snooty headlines such as “How on earth did Harold Pinter and Danny Dyer become such good friends?” in The Spectator.

However, it is also true that for every individual whose life was transformed through a love of culture, you’ll find plenty of others who’ll tell you they had an interest discouraged and knocked out of them.

Many might see their own story as a weird anomaly. It’s the same reason we see, say, Welsh male voice choirs as charming quirks and not evidence of a rich, self-made musical culture among working people. We need to give people their due, and see them for what they are: not anomalies, but a big part of the foundations of British culture.

In the 1990s, I was fortunate enough to edit The Face magazine, an internationally successful and influential magazine that was founded by the working-class Nick Logan. If The Face was not entirely about working-class culture, it was certainly driven by a distinctively modern, multiracial British working-class energy, and many acclaimed writers and artists came up writing, taking photographs and designing for it.

Inspired by that, I worked with New Writing North and the actor Michael Sheen to launch a magazine specifically for new and established working-class writers. Called The Bee, we’re publishing stories and photographs documenting the whole spectrum of 2020s working-class culture. The response has been incredible, and unanimous in confirming the need, and I hope that ultimately we can help to restore a truly great British traditional voice.

I don’t doubt that it’ll be entertaining too: after all, as Stephen Daldry, the film director, says, “The really successful work in England tends to be working-class stories.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks