Rewriting history: It’s time to recognise the black Americans that fought for their own freedom

Lincoln wasn’t a beacon for the abolitionist movement and slavery didn’t give modern black athletes a genetic competitive edge. Let’s stop crediting white people for black freedom and start remembering who actually fought, and died, for it, writes Ahmed Twaij

History is often narrated to us by those in power. Contributions of black Americans to the building of the US have often been swept under the carpet as history books are written by the mainly white individuals clenching influence. Each February a whole month has been dedicated to black history, but for too long black accomplishments have been overlooked, with white Americans taking the credit. Winston Churchill once said: “It will be found much better by all parties to leave the past to history, especially as I propose to write that history myself.”

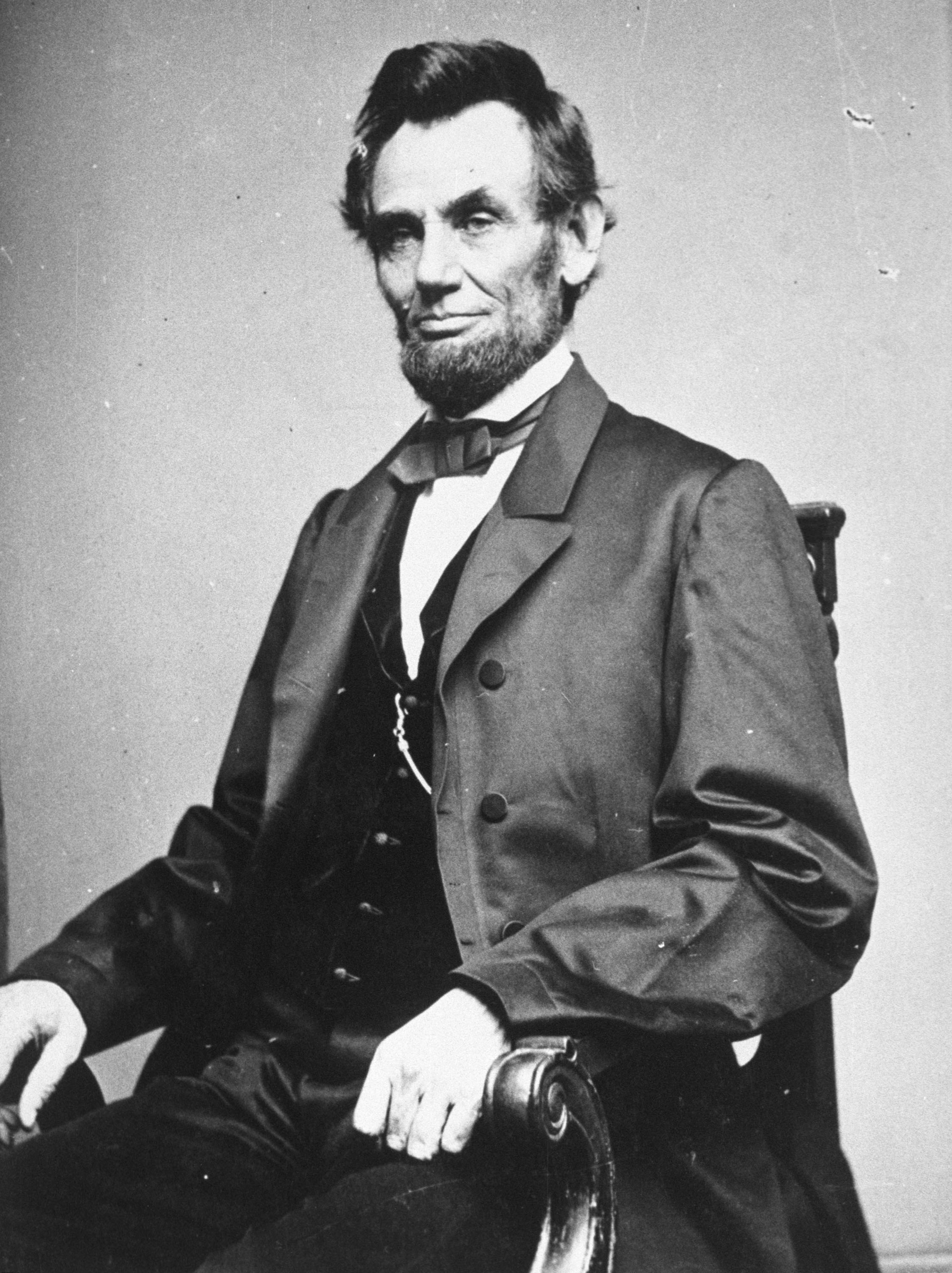

In October, standing tall with his chest puffed out and glowing orange under bright studio lights, Donald Trump, in his final presidential debate with Joe Biden, claimed with all seriousness to be the least racist person. Not for the first time, he declared: “Nobody has done more for the black community than Donald Trump. And if you look, with the exception of Abraham Lincoln, possible exception … nobody has done what I’ve done.”

For now, let us brush past the ridiculous notion that Trump is even comparable to Lincoln or the delusionary suggestion that he is anything but a bigoted racist. Even the assumption that Lincoln is the gold standard for black American freedom is inherently racist in itself. Once again, it credits white America for the achievement of black Americans. We should be recognising black Americans for their own push towards freedom and not suggesting that they owe something to white Americans. If anything, the reverse is true.

When thinking about black civil rights, Lincoln is not often the first name that comes to mind. Take a wander around Washington DC’s glorious National Museum of African American History and Culture (a must visit if you are in the city), for example, and references to the assassinated president are minimal. Instead, whole sections are dedicated to individual African Americans celebrating their own fight for freedom. Sure enough Lincoln signed into effect the Emancipation Act, and he should be admired for the achievement. If you really think about it, though, that was indeed the bare minimum. Forced enslavement of fellow human beings should never have existed and to suggest a white American, living in a White House built by slaves with all the privileges afforded to him based on the colour of his skin, was responsible for emancipation is absurd. Crediting Lincoln takes away from the black Americans that lost their lives and those that literally fought in their struggle for freedom.

Frederick Douglass, a black American born a slave (he changed his name from Frederick Bailey to avoid capture), risked his life to escape his shackles in 1838. He is just one example of someone we should be crediting for the abolition of slavery. With his new-found freedom in his early twenties, Douglass quickly moved to support the abolitionist movement and grappled with the white American political class to allow black Americans to enlist in the army, effectively allowing them to fight for their own freedom in the American Civil War.

Despite Lincoln using his executive wartime powers to sign into effect the emancipation proclamation, Douglass spoke frankly of his perception of the president, announcing to a crowd, “Abraham Lincoln was a white man’s president”, making it more ironic for President Trump to compare himself to his predecessor. Lincoln, speaking at his fourth US Senate debate with Stephen Douglas, showed that he did not believe in racial equality, stating: “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favour of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races.” Lincoln instead believed in colonisation: that all freed black slaves should be sent to Africa or Central America. Speaking to a delegation of freed black men and women in the White House in 1862, Lincoln’s solution to addressing the “differences” between black and white Americans was that it would be “better for us both, therefore, to be separated”. Had Trump even slightly looked into the history of Abraham Lincoln, he may have noticed that he is not the ideal freedom fighter for black civil rights.

The list of of black Americans we should be crediting for the struggle for emancipation is unending. Harriet Tubman, for example, who also escaped enslavement, undertook some 13 missions to rescue approximately 70 enslaved black Americans. For her achievements, Tubman was nicknamed “Moses of her people”. Andre Cailloux, another former slave and key character in black liberation, was one of the first black officers in the Union Army, and later gave his life defending his country, in search for black freedom. Alexander Augusta was one of the first black surgeons fighting for freedom in the Union Army, yet upon his return to Washington DC was refused railroad access. William H Carney, Jefferson Shields, William Wells Brown; the list of black Americans fighting for their own freedom goes on. Yet those like Trump try to affirm black Americans owe their freedom to white America. Without freedom fighters risking their lives like Douglass, Tubman and Cailloux, the conditions paving the way for Lincoln to put into law the Emancipation Act would never have existed.

Not only should we be crediting black Americans for their own fight for freedom, but the United States in general owes much of its so-called greatness to black Americans. The well known statement holds true: “America was built on the backs of slaves.” Yet whenever America’s history is narrated, from the rise of democracy and independence to more modern achievements, it is white Americans who have taken much of the credit. I remember sitting in an underground comedy club in New York earlier this year (pre-Covid, I must add) when a black American comedian, referring to Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan, peered down his microphone at the audience mockingly and said: “Well as a black man, it really depends how far back you wanna go to make America great again.”

Without black Americans, much of what makes America “great” would never exist. Well before Wall Street, the first big economy in the US was the cotton industry. Even the current financial system was founded on slavery, as things like mortgages were securitised by slave property stimulating the development of American capitalism. It is hard to find anything that doesn’t have roots in slavery, for which black Americans receive no credit for. It is unsurprising that the institution of slavery built America into the colossus that it is today, what is scary is how entrenched the concept still is in today’s economy. The historians Sven Beckert and Seth Rockman write: “American slavery is necessarily imprinted on the DNA of American capitalism.”

In more recent times, there are plenty more role models in the liberation movement. Many seek inspiration from the civil rights movement of the 1960s, with Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X becoming key figures in the move towards justice and equality, something which they eventually made the ultimate sacrifice for. These are the characters we should be crediting for the move towards greater equality. Malcolm X even changed his surname to X, recognising that his name at birth was assigned to his ancestors by their slave owners.

In the London 2012 Olympics, black athletes once again dominated track events at the tournament. In fact, by 2012 no white athlete had contested in the 100m final for 32 years. The BBC oddly decided to highlight this fact with a nine-minute segment on eugenics. The presenter suggested black athletes winning track events “brings the whole issue of nature or nurture into very sharp focus”.

When things were going well, I was reading newspapers articles and they were calling me Romelu Lukaku, the Belgian striker. When things weren’t going well, they were calling me Romelu Lukaku, the Belgian striker of Congolese descent

The film somehow linked Darwin’s On the Origin of Species with the Nazi eugenics movement, slavery and the success of black athletes. “Who was it that survived being put in shackles, packed into slave ships and taken across the ocean?” the narrator asked. “Who was it that survived the life of forced labour on the cotton and sugar plantations? The fittest, only the fittest could survive.” In other words, black athletes had white Europeans to thank for enslaving them so their muscles could develop so significantly during hard labour that it had given them a long-term competitive advantage. Yet again, black excellence wasn’t something that could just simply be celebrated.

Why did we even have to question black excellence? Why has this never been an issue in sports dominated by white people? In 1975, Arthur Robert Ashe Jr was the first and only black man to win the Wimbledon singles tennis Grand Slam, in a sport that has otherwise been overshadowed by white athletes. Yet, the thought of writing a eugenics piece about how white tennis players are only good at the sport, not because of hard work and training, but because of inherited genes from some abstract historical period is ludicrous. Would we ever suggest that Rafael Nadal, the joint holder of the most men’s single tennis Grand Slam titles, has only been successful thanks to Spain’s brutal colonial past somehow giving him a competitive edge when swinging a racket? The reality is that tennis is an expensive sport and half of the professional players make little to no money from it. It costs around $306,402 to develop a player aged between five and 18, outpricing many budding black American athletes from the sport. Thanks to the legacy of redlining, affordable US Tennis Association centres are often expensive journeys for aspiring athletes.

When things are going well for black athletes they are quickly welcomed by the public, but as soon as something negative happens the appreciation jades. Romelu Lukaku, a black Belgian professional footballer, highlighted this when he said: “When things were going well, I was reading newspapers articles and they were calling me Romelu Lukaku, the Belgian striker. When things weren’t going well, they were calling me Romelu Lukaku, the Belgian striker of Congolese descent.”

It’s never enough to credit black athletes for their own excellence. When it comes to crime, however, ethnicity is quick to be pointed out. But the legacy of slavery, protracted underfunding of black neighbourhoods and structural racism are never addressed, because that would insinuate blame is attributed to white America. Joe Biden has never called black Americans “superpredators” as Trump claimed at the last presidential debate, but former secretary of state Hillary Clinton (who is often, counterintuitively, lauded as a progressive) did and that is something that must be addressed. Imagine blanket labelling white Americans as terrorists after the Department of Homeland Security stated white supremacists were the deadliest US terror threat.

Black Americans have struggled for positive acknowledgement for as long as the Americas were colonised. Because slaves were not classified as citizens, they were barred from filing patents for inventions. Shontavia Johnson, an intellectual property law professor at Duke University, explains: “One group of prolific innovators, however, has been largely ignored by history: black inventors born or forced into American slavery. Though US patent law was created with colour-blind language to foster innovation, the patent system consistently excluded these inventors from recognition.” In 1857, for example, Oscar Stewart, a white slave owner, successfully stole and reaped the financial rewards of a cotton scraper devised by a black inventor named Ned who was refused a patent on the grounds of him being a slave. Similarly, Henry Boyd, born into slavery in 1802, was forced into partnering with white craftsmen to secure a patent for a bedstead he invented.

The act of taking credit is not limited to black communities. One example is Ibn Nafis, an Arab scholar, who first described blood circulation around the body in the 13th century, yet history credits William Harvey, a white British physician, with the achievement some 400 years later.

Trump’s claim that he has done more for black Americans than any US president before him overlooks his immediate predecessor Barack Obama, who broke the largest barrier of all by becoming the first black president of the United States. Trump, to his credit, did sign into effect the First Step Act, a bipartisan prison reform bill, but it pales in comparison to the achievements of other presidents, who owe their successes to black Americans.

Take, for example, Lyndon B Johnson, who shepherded the Civil Rights Act (dubbed a historic milestone by the White House last year), Fair Housing Act and Voting Rights Act. President Johnson would never have achieved such landmark policy changes had it not been for Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr and millions of black Americans fighting for their own freedom on the streets of America while the US government violently suppressed any movement for justice. I still quiver at the thought of images of police dogs ferociously attacking peaceful protestors in Birmingham, Alabama. Fast forwards to 2020 and history repeats itself: the sitting president declares he has championed black communities, while simultaneously deploying a “heavily armed” military against said black communities peacefully protesting for equality.

To achieve civil rights, Malcolm X was willing to, and eventually did, put his life on the line. “The ballot or the bullet. It’s liberty or death. It’s freedom for everybody or freedom for nobody,” Malcom X famously announced. The concept of fighting to the death for basic civil rights is probably alien to Trump, especially while he was sitting in the comfort of his penthouse suite on New York’s Fifth Avenue campaigning for the death sentence for the innocent Central Park Five children of colour.

So no, President Trump cannot compare himself to Abraham Lincoln or even claim to not be a racist, as under his watch he himself promoted white supremacy and called neo-Nazis “very fine people”. Along with a slew of racist policies, from the Muslim ban to calling Mexican immigrants “rapists”, the former real estate mogul was twice sued by the Department of Justice, once in 1973 and again in 1978, for not renting to black people.

Had it not been for black Americans fighting for their rights, America would never be the democracy it is today, yet credit is usually only ever given to the founding fathers. Black Americans have constantly had to struggle for equality, justice and freedom throughout the history of United States. To suggest black Americans owe their accomplishments to individuals like Abraham Lincoln or Donald Trump, is racist in itself. It takes away from the struggles of millions of black Americans, who through generations have been challenged at every corner, from slavery to structural racism.

It is long overdue that we recognise black Americans for their own achievements and not credit white Americans for them or try to find excuses for why black Americans are succeeding.

We should be celebrating accomplishments. Malcolm X, Harriet Tubman, Martin Luther King Jr and plenty of others have achieved more for black Americans than Trump or Lincoln, we should never forget that. And here’s to you Beyoncé, LeBron James, Serena Williams and the never-ending list of black Americans at the top of their game.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks