‘Shameful but necessary’: How the Romanian rulers who starved their people met their end

On Christmas Day 1989, after a tumultuous year, Romanian leader Nicolae Ceausescu and his wife were executed by firing squad against a toilet block. But what led to this egregious event, asks Mick O’Hare

In a rambling military and civilian cemetery in Bucharest’s Sector 6 you can find the graves of Nicolae and Elena Ceausescu. Considering the ostentatious lifestyles of Romania’s former first couple, the graves, in Ghencea Cemetery, are rather underwhelming. On a misty morning you might walk right past, save for the ever-present flowers and photographs that generally embellish them, in contrast to the unadorned headstones around and about. Their son Nicu is also buried alongside.

For 24 years they ruled Romania almost in tandem, simultaneously espousing hardline communist rhetoric while living lives of opulence as the Romanian population suffered the hardships and privations that were a common feature of life in the communist nations of eastern Europe. But in 1989 things had been changing. Throughout that astonishing year the people of those nations threw off Soviet hegemony. One by one Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and East Germany, as evinced by the symbolic dismantling of the Berlin Wall in November, displaced their communist rulers, in the main by peaceful means. Not so in Romania.

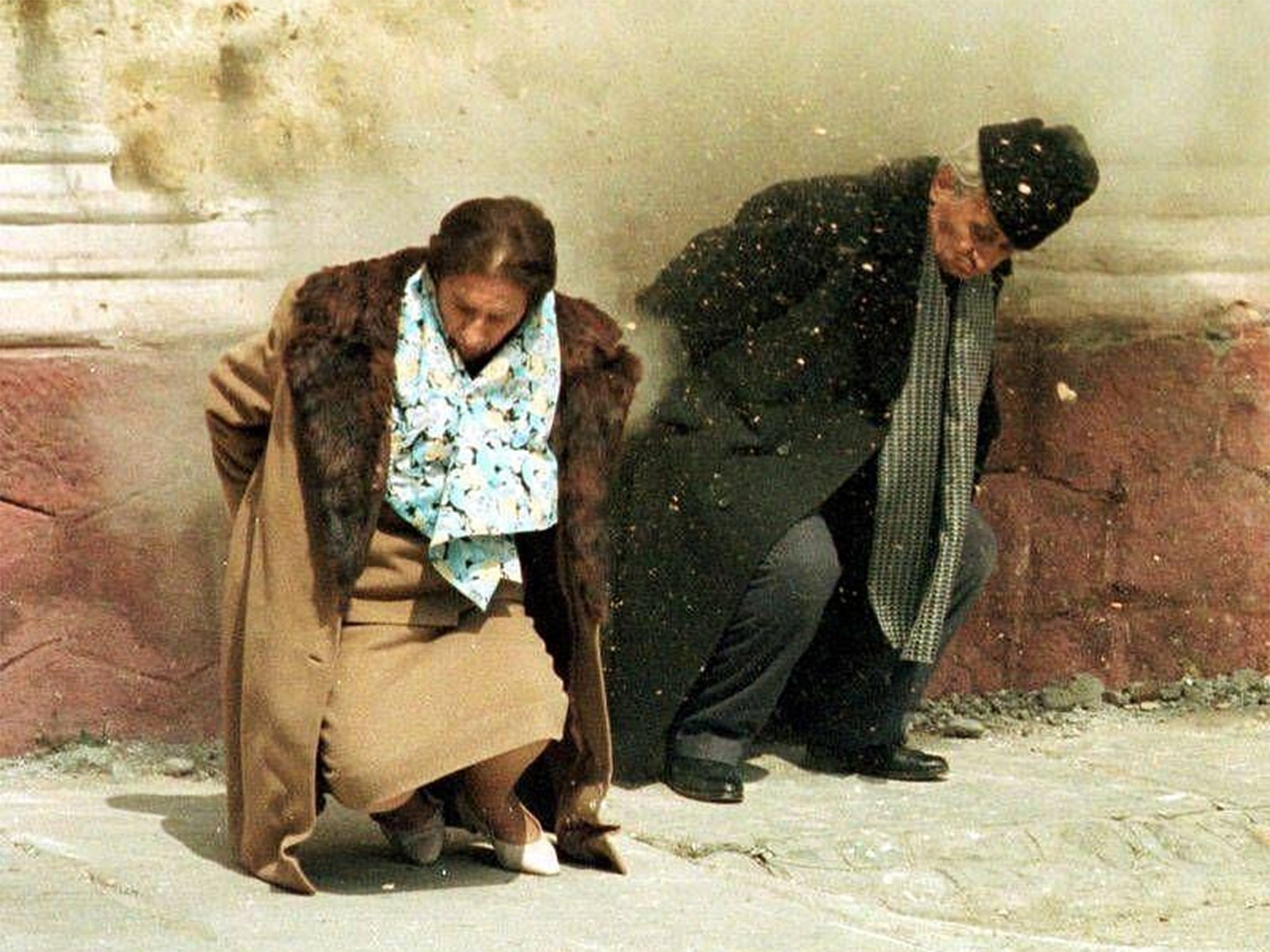

On Christmas Day 1989, after what can best be described as an egregiously conducted summary trial, at worst a kangaroo court, the Ceausescus were dragged into a small square in a military base near Targoviste, lined up against a toilet block and shot. The images were shown on television in Romania and around the globe. And while it is true Ceausescu was a brutally oppressive leader whose rule had discharged misery upon his citizens while he lived lavishly alongside his wife, the manner of their demise shocked a watching world. How had it come to this?

It was the denouement of an extraordinary year during which the Soviet Union had voluntarily given up its once implacable hold over its satellite states. Romania would be the last domino to tumble. And in Romania, unlike elsewhere, the last days of communism would prove violent.

While the once solid allies of the USSR declared democratic independence, Ceausescu ignored the pleas of his people and – perhaps more significantly – the leaders of his former fellow communist nations who urged him to reform. The Romanian dictator had long been a law unto himself, distancing his nation from the Soviet-backed Warsaw Pact military alliance, especially after the Pact invaded Czechoslovakia in 1968, and defying the Soviet-backed boycott of the 1984 Olympic Games in Los Angeles.

His rule was essentially a cult of personality. He intended to sit it out, convinced of his own invincibility and the self-deluding righteousness of his socialist cause, seemingly incapable of understanding that it was only upheld by his overbearing, often vicious police and oppressive security services and the threat of Soviet intervention.

But that threat had now vanished. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev had announced his nation would never again interfere in the affairs of others and the peoples of eastern Europe had taken note. And seeing what was happening elsewhere, the Romanian population was suddenly emboldened. The first protests on 16 December in the western city of Timisoara were by members of Romania’s Hungarian minority, demonstrating against the removal of a Hungarian clergyman Laszlo Tokes who had spoken out against the Romanian government.

We were encouraged by what our families told us had happened in Hungary. And we needed to air our grievances

Although the state-controlled press was not reporting on dissent either within Romania or across eastern Europe (there was no mention of the fall of the Berlin Wall in the week after its breaching), word had reached Timisoara. “We were encouraged by what our families told us had happened in Hungary,” says Bertalan Toth, now 64, a member of the Hungarian minority in Timisoara. “And we needed to air our grievances.” But initially the protests seemed small and were not attended by Romanian speakers. In fact, inside the confines of the Romanian Communist Party all was looking good for Ceausescu who had just been elected for another five-year term in November.

The police thought they had put the lid back on the simmering dissent in Timisoara but the following day protests resumed. “By now word had spread about what was happening around the continent and we had Romanian speakers backing us too. In fact there were more Romanians than Hungarians,” says Toth.

This time the military was sent in, presumably on Ceausescu’s orders and, although this has since been disputed, it’s what the protestors believed and so the army came under attack. It had been a needless escalation but now the city was burning, martial law was declared and tanks entered the streets. When demonstrators defied the curfew, troops opened fire. A large number were killed, others seriously injured. There were many arrests.

On 20 December with Nicolae Ceausescu on a government visit to Iran, Elena Ceausescu despatched her prime minister Constantin Dascalescu to Timisoara to take control. He offered to free those arrested but was met with protestors instead demanding that Ceausescu resign. Workers bussed in to replace the striking dissidents instead joined them. Years of state-imposed austerity were coming home to roost. Ceausescu returned from Iran as western media, transmitting into Romania, began to disseminate news of the Timisoara revolt. Ceausescu’s next move cemented his downfall.

Still complacent, he planned to make a public speech to the people on 21 December. Formerly faithful supporters were invited, and others – it has been reported – under threat of losing their jobs if they did not give outward shows of support when he spoke. Around a hundred thousand gathered in Piata Palatului, furnished with red flags and huge pictures of the dictator. But the crowd would not play along. As little as two minutes into his speech there were boos, jeers and cries of “Timisoara”.

And then came one of the defining images of 1989. Ceausescu raised his hand to quell the shouts. The stunned expression on his face when the catcalls didn’t stop marked the very moment his regime lost its legitimacy, but more significantly it was the point when he finally realised it himself. As an emblematic image from that momentous year, it is the equal of the man atop the Berlin Wall with a pickaxe or Lech Walesa surrounded by Solidarnosc supporters in the shipyards of Gdansk.

“He stopped, paused. From where I was standing well back in the crowd at first I thought it was for effect,” says Alexandru Balan a factory worker then aged 33. “Then booing began and cries of “Timisoara” and “f*** you” and it became clear he was unsure. It was exhilarating because this man had ruled every aspect of our lives since before we could remember. And none of it had been good whatever lies he had spun. I was there when the people turned.”

The speech was being broadcast nationwide in an attempt to show that Ceausescu retained control. It had the opposite effect. Bodyguards rushed the Ceausescus from the balcony back into the government building as rioters took to the streets. Protesters hit the centre of Bucharest carrying Romanian flags with the communist insignia ripped from their centres. But still Ceausescu refused to compromise and again sent in the military. The final death toll remains disputed – upper estimates say as many as 1,200 were killed either in the Timisoara uprising or later on the streets of Bucharest as some sections of the military stayed loyal to the regime.

When columns of workers were seen heading for the city on the night of 21 December the Ceausescus had no option but to flee. But, crucially, they delayed. The teetering leader intended to speak to the people again and helicopters dropped leaflets telling the protestors to return home to enjoy the forthcoming Christmas feast. It was a terrible decision – many of the population had difficulty finding enough to eat let alone “feast”.

This man had ruled every aspect of our lives since before we could remember. And none of it had been good whatever lies he had spun. I was there when the people turned

The military began to switch sides amid confusion in the Defence Ministry. When minister Vasile Milea was either murdered under Ceausescu’s orders or took his own life – support for the regime collapsed and Ceausescu finally realised the game was up. With protestors closing in and the military no longer prepared to defend him he fled with his wife in a dramatic escape by helicopter from the Bucharest rooftops only seconds before his pursuers reached the aircraft.

But the pilot was not happy carrying the dictator to safety and near the town of Titu he put down in a field after raising specious fears about being in range of anti-aircraft fire. The Ceausescus flagged down the car of Nicolae Petrisor, who recognised them and, equally speciously, told them he could find them a place of safety at an agricultural institute. There he locked them in a room and called the police who took them to the military base at Targoviste. Their fate was sealed.

Ceausescu might have suffered the fate of other leaders of eastern European communist nations in 1989 – resignation and ignominious retirement – had he simply upheld socialist ideals that were always likely to fail in bringing prosperity to his nation. But he went far beyond bad political judgement – it was his stance outside the confines of simple ideology that created such bitterness and seriously impinged on the population’s wellbeing.

In 1981 he began a programme of austerity, which aimed to liquidate his nation’s enormous national debt. This meant food, clothing and fuel were rationed. Malnutrition became commonplace and Romania had Europe’s highest infant mortality rate. There was more too, much of it linked to a mixture of paranoia and intransigence. The Securitate, Romania’s secret police, was a ubiquitous presence, deliberately intended to foster fear among the public. Poverty and disease were widespread yet the Ceausescus, in full view of a watching nation, constructed the House of the Republic – among many other grand buildings – a sumptuous palace which now houses the Romanian parliament. Residents were evicted from their homes so it could be built. Resentful anger, not surprisingly, was rife.

And for years Ceausescu insisted that HIV was not sexually transmitted and contraception was banned, condemning many innocent people to needless early death. “The underground gay community in Bucharest was aware of how HIV was transmitted,” says activist Adrian Petrescu (not his real name) “And condoms could be smuggled in through Yugoslavia, but the official line was that HIV was a western plot.”

So when the people finally rose against the Ceausescus there was more than just the everyday grind, the lack of hope, the lack of infrastructure and the lack of opportunity shared by all the other nations that overthrew communism in 1989. In Romania it wasn’t just the ideology, which can to a certain extent be defended in the abstract, it was more what Ceausescu deliberately chose to inflict on his people, while giving no impression of sharing the nation’s ordeal.

Condoms could be smuggled in through Yugoslavia, but the official line was that HIV was a western plot

Did the manner of his downfall, and concurrent violence – the only communist nation in 1989 to experience a murderous overthrow of its regime – create a legacy that differed from its erstwhile socialist allies? In many ways no. There were repercussions at the European Court of Human Rights who contended the Ceausescus’ right to a fair trial had been violated, but once the fighting died down and the new government led by the National Salvation Front (NSF) took power and arranged free elections, the course for Romania was always likely to be determined by free-market democracy. As elsewhere the transition was painful in parts, but perhaps resented less because of the privations suffered under Ceausescu.

“My parents were poor before and poor after the revolution,” says Maria Fieraru, an office worker aged 42 who now lives in London. “But the poverty wasn’t a state-imposed policy any more. They were both fortunate to work in industries that expanded after communism ended and can live off their state pensions now. There are older people who still extol the certainties of Ceaucescu’s communism but not many new recruits to the cause.”

The NSF was careful, also, not to bring in rapid economic reforms, allowing time for the economy to adjust. Eventually former national assets were privatised and Romania followed its erstwhile Soviet satellite allies into Nato in 2004 and the European Union in 2007. Problems still exist today, however, and child poverty is still high in terms of the developed world and so younger people especially began to leave their country after 2007 to work in richer western nations. The collective Romanian diaspora is reckoned to be almost 4 million, the fifth highest in the world.

There has also been re-evaluation of the revolution and its prologue in the intervening 30 years, maybe even anger at how the Ceausescus’ trial was conducted. “I know what happened, even though I was only six at the time,” says Maria Radu an English translator. “They should have been tried properly, but other people wanted power and needed the Ceausescus out of the way.” She is talking about Ion Iliescu, who became president of the new Romania.

Even Iliescu has admitted the episode was “quite shameful” but, he adds by way of defence, “necessary”. The argument he uses is that the Ceausescus needed to be removed so that nobody would be in a position to fight for them. In effect, he is saying that killing them stopped further bloodshed.

Victor Stanculescu, an army general who took control of the Ministry of Defence during the revolution and was instrumental in organising the Ceausescus’ trial, concurs. “It was not just, but it was necessary,” he told the BBC before his death in 2016. “If we had left it to the people of Bucharest there would have been lynchings.” However, his testimony is clouded by the six years he served in jail for ordering his troops to fire on the protestors of Timisoara (before he switched sides), charges he always denied. And arguably both Iliescu and Stanculescu have a point. Fighting died down by 27 December although many responsible for the bloodshed have never been identified.

It was not just, but it was necessary. If we had left it to the people of Bucharest there would have been lynchings

Even so, the fact that the Ceausescus were shot on Christmas Day has also been a source of anger in a deeply religious country “All wrong,” says 74-year-old Simona Dobre, a retired telephonist. “Shameful. We were glad to see them go, but shooting them on Christmas Day could have made martyrs of them.” Other Christians point to the fact that atheist Ceausescu demolished churches during his reign. “Christianity owed him nothing,” says churchgoer Elena Teodoroiu, 68. Others even argue that Romania has not made the rapid progress to a modern democracy as it might have exactly because of the shame surrounding their deaths. “There is always a political crisis, always another economic crisis,” says Dobre. “We could never come to terms with the collective guilt. And those who carried it out were never brought to justice so we sit and fester.”

That may or may not be so but for those who lived through 1989, it was the trial itself that provided an insight into what Romanians had been living through since Ceausescu took power and it is forever impinged on the minds of those who saw it on television. Mercy was clearly in short supply. Decades of bitter grievance, poverty and hunger were about to be unleashed. On 25 December an extraordinary military tribunal under 10 military judges was convened at Targoviste. The charges included genocide by starvation and subversion of state power. The outcome was already predetermined.

The hastily appointed defence lawyer Nicu Teodorescu insisted the Ceausescus plead insanity as the only way of avoiding the death penalty. But, not surprisingly for people with an overwhelming belief in their self-importance, they were having none of it. Nicolae refused to accept the legitimacy of the court, and with good reason. But it would make no difference.

The trial lasted two hours. No actual proof was brought, nor was any evidence presented. It was crude. It is clear on reading the transcript or watching the video that Elena becomes aware of their fate before her husband. He is still disputing the legitimacy of the military court, accusing them of being backed by the Soviet Union whom he had always distrusted, even as she realises what the outcome will be. “We are powerless now,” she tell her husband towards the end.

They were dragged out, begging for mercy, and shot in the freezing courtyard. It has been said that Elena called the firing squad “sons of bitches” but elsewhere she can be heard begging them: “Why, why? I raised you like a mother.” They both wept as Nicolae sang the “Internationale”– attempting to maintain his socialist credentials until the end. The military commander had asked for five volunteers.

It is likely apocryphal, but the story goes that all 80 guards present fired and that more than 120 bullets struck their targets. It happened so rapidly that the person delegated to film the execution only saw the last moments and then videoed the doctor showing the faces of the dead couple as proof of their demise. Even so, this was not enough for some. The bodies were exhumed in 2010 for DNA checks to dispel conspiracy theories that they had escaped.

Footage of executions, of course, was nothing new, but the internet has given free rein for the likes of Isis to post gruesome murders online as a tool to promote their ideology. Usually they have been used to instil fear or for propaganda purposes, but the filming of the Ceausescus’ execution was – probably deliberately – intended to provide an outlet for all the pent-up visceral hatred and outrage of the Romanian people. There was international condemnation of the trial but, on the other hand, little sympathy from foreign governments and democratic nations the world over. Meanwhile, messages of support flooded in for the new government replacing Ceausescu.

The trial was illegitimate, the immediate executions shocking. Whatever one’s politics or whatever one thinks of the Ceausescu regime, or the death penalty in general, to see a woman pleading first for her life, and then to be allowed to die beside her husband can never be dressed up as edifying. Her distress is palpable and raw. One of the guards who shot them regrets his actions today. “When you kill two unarmed people, it’s a big deal. I wouldn’t wish this on anyone,” says Ionel Boyeru of his life of depression and turmoil since. They were to be the last (semi) judicial deaths in Romania. Thirteen days later the nation outlawed the death penalty. Nicolae Ceausescu, who had effectively presided over the deaths of many thousands through his political intransigence and callous disregard, was the last victim of his own regime.

You’ll find the odd tourist in Ghencea trying to find the old dictators’ graves, but mainly it will be older people, still of the opinion that life was better before 1989, hence the ubiquitous flowers and photographs that wreathe the gravestones. Because of the manner of their deaths, the Ceaucescus will remain martyrs to some. The victims of their regime would disagree vehemently and with justification. On Christmas Day, 30 years on, maybe only they should deserve our sympathy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks