On her 200th birthday, Florence Nightingale’s legacy has never been more important

In 1860, regularly washing your hands and evidence-based practices revolutionised modern healthcare. Now, those same values are shaping the fight against coronavirus, writes Olivia Campbell

Florence Nightingale was a trailblazing figure of modern nursing whose pioneering ideas and reforms, from notions of cleanliness and hygiene to the effectiveness of evidence-based healthcare, are just as relevant today as they were 160 years ago.

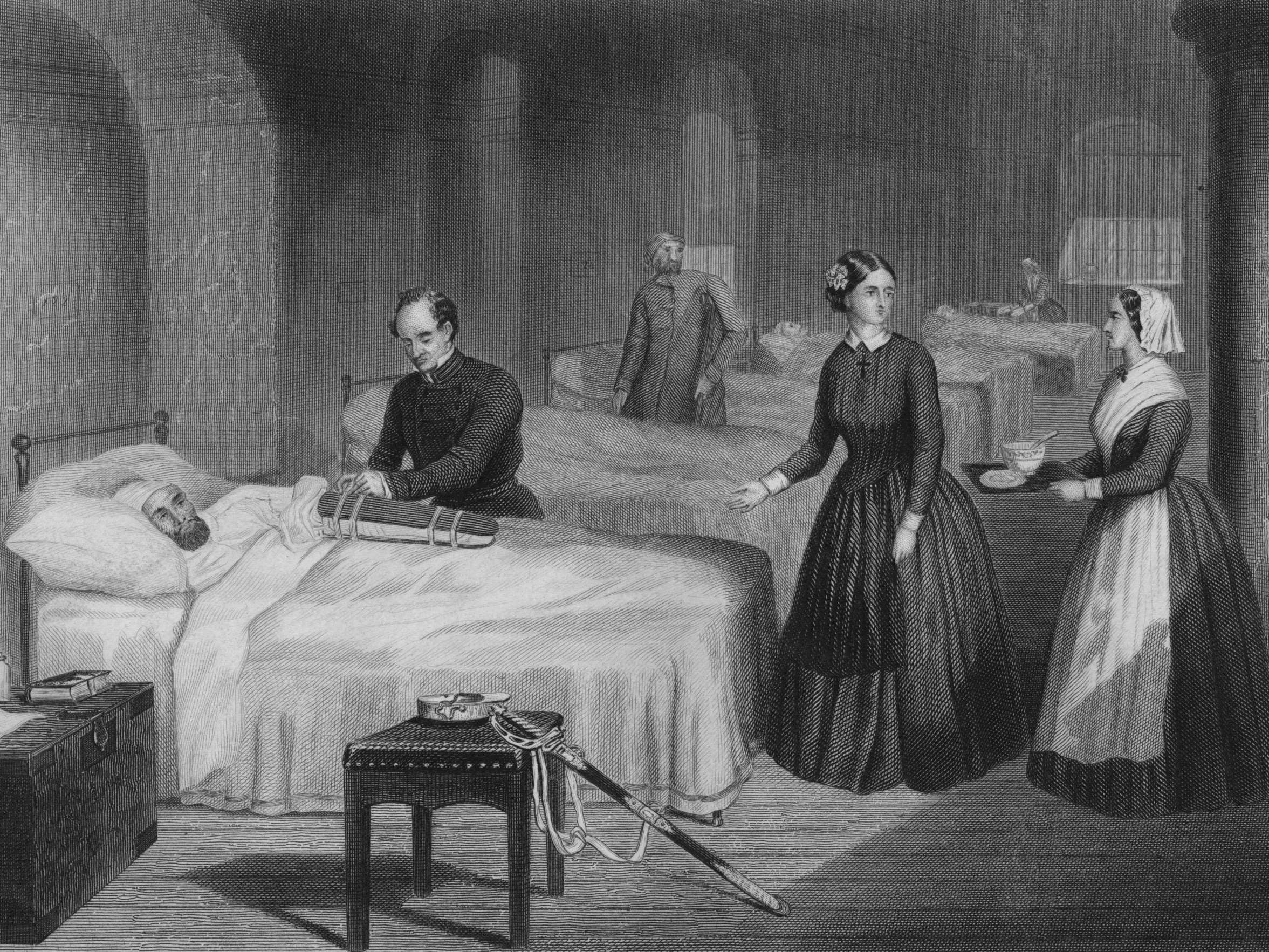

Today, two centuries since the birth of the “lady with the lamp” – so-called for tending to wounded soldiers at night during the Crimean War – the world faces another crisis. The global death toll of coronavirus stands at nearly 300,000, with hospitals and care homes pushed to their limits. As doctors, nurses and scientists race to turn the tide against the virus, some of the principles Nightingale championed in 1860 are the very weapons that will help us eliminate it.

“Today, her legacy can be found in nursing standards and hospital design principles worldwide,” explains Kristin Buhnemann, assistant director at the Florence Nightingale Museum. “She remains an inspiration to healthcare professionals around the world, which is vitally important during times like these.”

Throughout her life, Nightingale stressed the importance of cleanliness and hygiene in hospitals, as well as at home. These ideas don’t sound revolutionary today – the concept of washing hands and surfaces had even been circling the upper echelons of academia and medical science in the 1800s – but they were at odds with practices of the time and she was the first to attempt to turn the concept into reality.

“In the mid-19th century, hospitals were dirty and dangerous places,” says Buhnemann. “If you were wealthy enough you would be treated at home, and only those without hope would go into hospital.” So the rigorous standards we enjoy today are partly due to Nightingale’s efforts all those years ago.

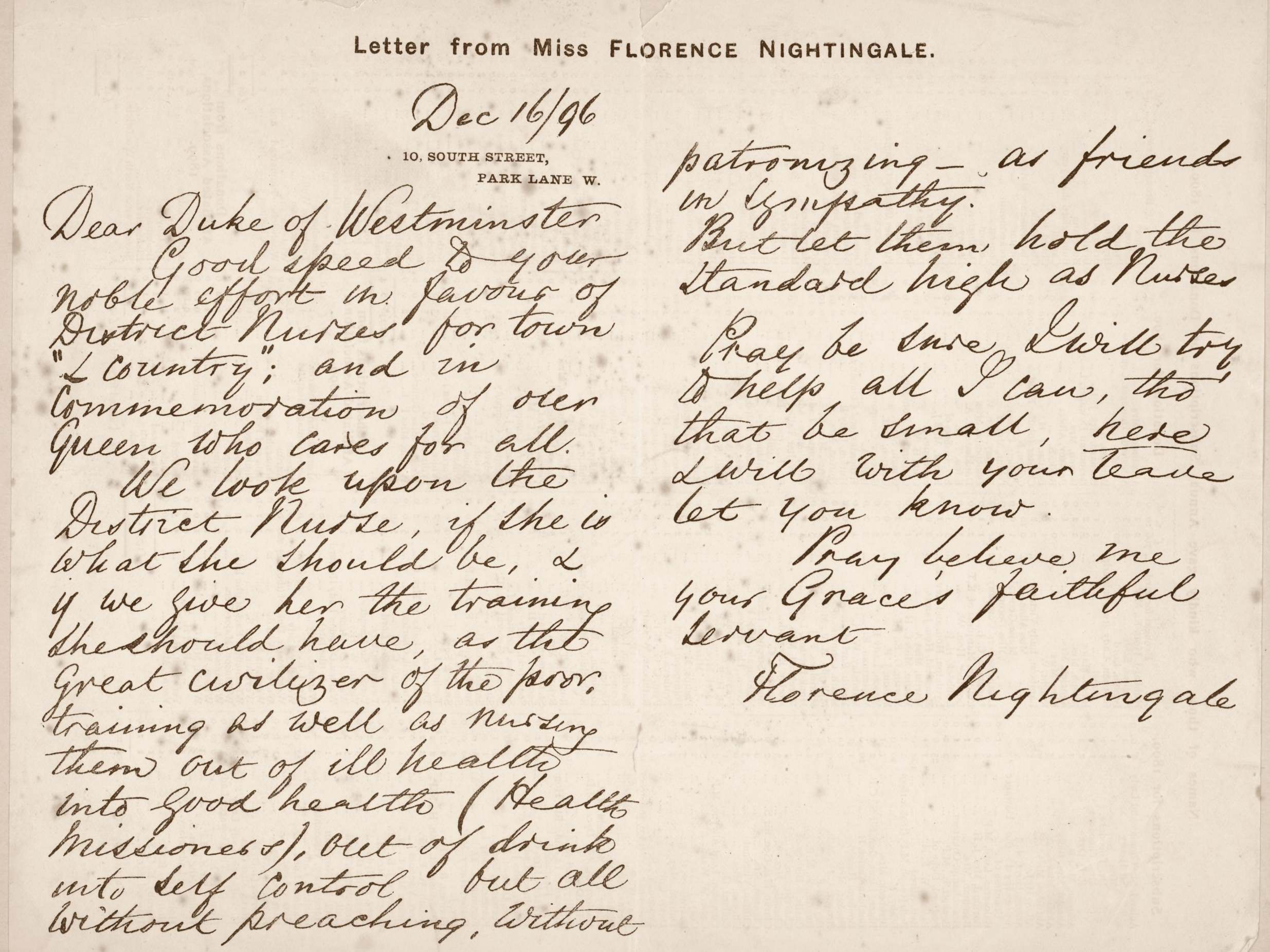

Nightingale is most well known for introducing the simple act of washing your hands. “Every nurse ought to be careful to wash her hands during the day,” she wrote in her 1860 book Notes on Nursing: What it is and What it is Not. In a world currently being ravaged by a deadly pandemic – and one in which hand sanitiser is at a premium – Nightingale’s words feel scarily prescient.

Handwashing has only been a vital practice in healthcare for the past 130 years or so. In fact, it was only towards the 20th century that it became a common procedure. In 1840 Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis, known as the “father of handwashing”, observed that mortality rates in maternity wards were significantly lower in institutions that practiced better hygiene techniques. Twenty years later, Nightingale, a keen reader and very much clued up on medical research, was successful in implementing these early notions of hygiene.

The popularisation of many of the techniques and practices we take for granted today stem from Nightingale’s time as a nurse in the Crimean War. The conflict, fought between Russia and the allied powers of Britain, France and Turkey, was a bloody affair. An estimated 366,513 casualties occurred, of which as much as 56 per cent were caused by disease.

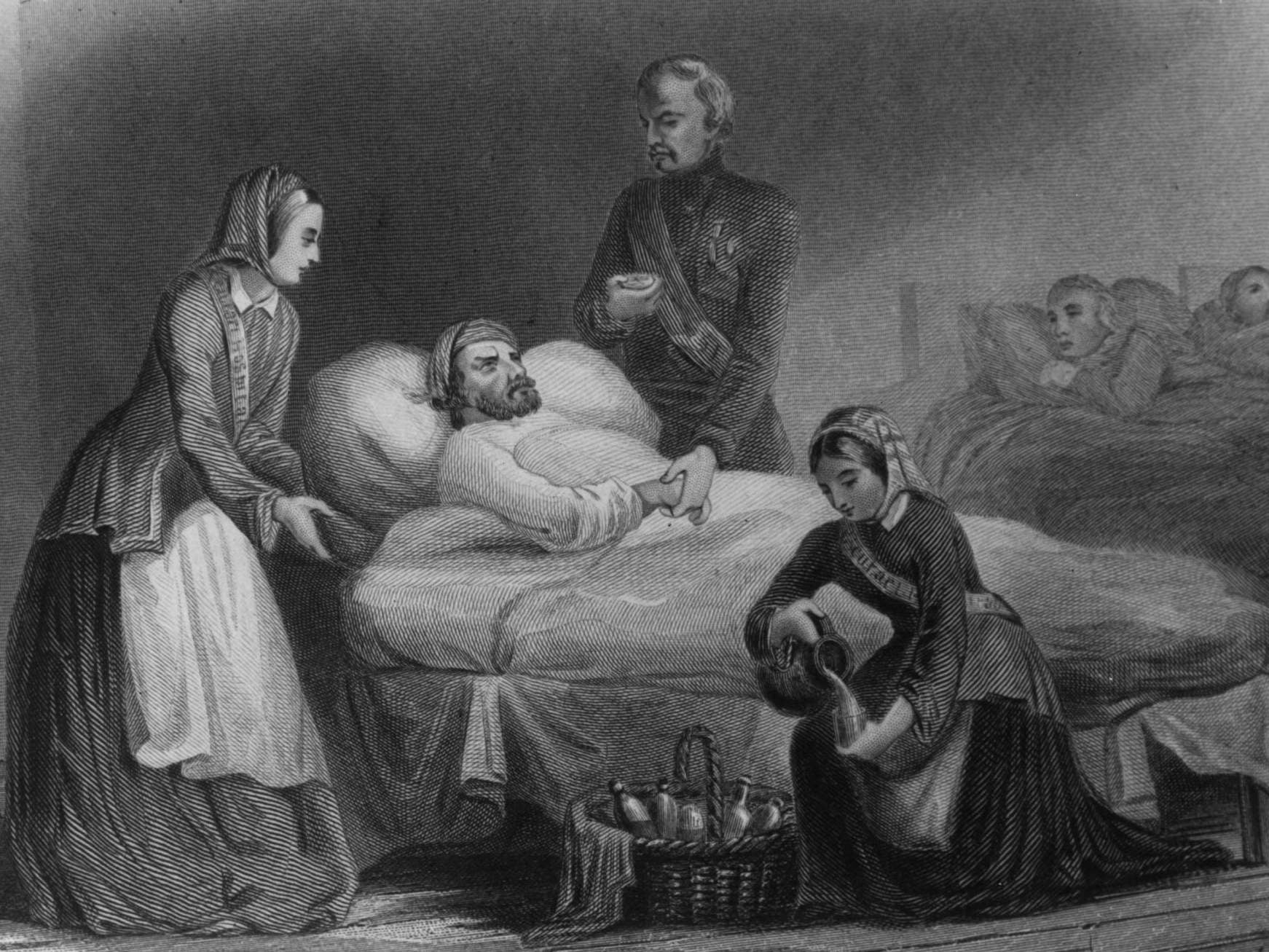

At the personal invitation of war minister and close friend Sidney Herbert, Nightingale and a party of 38 volunteer nurses travelled to Turkey and arrived at the Scutari Barracks in November 1854. To describe the scene that greeted them as carnage would be an understatement.

The barracks, which had been hastily built over a sewer, were “swarming with vermin, huge lice crawling all about their persons and clothes,” an assistant surgeon, Henry Bellew, said. “Many were grimed with mud, dirt and blood.” Many had contracted diseases such as typhus, dysentery and cholera and in some cases, had gone untreated for weeks. To Bellew, “the sight was a pitiable one and such as I had never before witnessed…”

Soon, Nightingale, imbued with a steely determinism to overhaul the barracks, charged her nurses with scrubbing down every inch and implemented regimented hygiene rules. They ordered new clothes to replace the lice-infested rags worn by the wounded. An order of care was established, and the hospital began running like clockwork – as opposed to the chaos Nightingale first encountered. She firmly believed “wise and humane management” was how infections could be contained and eradicated.

Indeed, her reputation as a caring nurse is more than familiar, but less well known is Nightingale’s role as a pioneer of statistical analysis and data. “She was a very methodical and systematic thinker,” says Dr Richard Bates, a history research fellow at the University of Nottingham and co-author of the forthcoming book Florence Nightingale at Home. “She went out of her way to collect data about the state of health and how this could be used to implement policy.”

She was intelligent, well-educated, and interested in statistics from an early age – she even became the first woman to be admitted to the London Statistical Society in 1858, Bates says. Throughout her life, her love of numbers and statistical thinking guided her. Francis Galton, a fellow statistician and polymath, even said that for Nightingale “her statistics were more than just a study, they were indeed her religion”.

While in Scutari, Nightingale collected data on the number of soldiers killed, injured or diseased, for which there was little or no systematic reporting before she arrived. She quickly gathered stats that showed that for every 1,000 injured soldiers, 600 were dying from infectious diseases.

“The data that Nightingale collected showed that the number of soldiers dying from their wounds was far, far lower,” Bates explains. “She had the numbers to show that if the army was to achieve lower death rates in future conflicts, then more attention needed to be paid to the sanitation and cleanliness of barracks and hospitals.” When she returned from Crimea, Nightingale received backing from Queen Victoria to persuade the government to set up a royal commission into the health of the army. She enlisted the help of William Farr, one of the founders of medical statistics, to analyse vast amounts of army data and translate it into diagrams that would show the information in a clear and accessible way for Victorian society.

Just like she ran the enquiry into the Crimean War, she’d be very interested in learning lessons and using this knowledge to implement policy. If she could see a way to save lives now or in the future, she wouldn’t relent until it was done

Her most well known graph was the polar area diagram, also known as the Nightingale rose or the coxcomb chart. The chart was divided into wedges, each representing a month, while the area showed the number of soldiers who had died during that month. Colour was then used to denote cause: blue represented death from preventable diseases, while red showed battlefield wounds and black showed other causes.

Nightingale had created the first amalgamation of the pie chart as a tool to demonstrate army failings and an urgent need for change. The endless coronavirus infographics we see today hark back to this distant pioneering method of data visualisation.

“Florence was able to look at data, draw conclusions and create a picture in her mind of the results,” says Buhnemann. “She discovered that accurate statistics were the key to understanding how and why things happened. One of her biggest legacies can definitely be found in evidence-based healthcare.”

Over 150 years later, it is one of the biggest weapons in the fight against coronavirus. Since the infection was first detected in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, every part of the pandemic has been broken down into numbers, from death tolls to testing capabilities, mass-collected by health organisations and governments around the world. This is a clear example of evidence-based healthcare – the global response is a result of the information we have.

The World Health Organisation uses a modified version of the template spreadsheet Nightingale created back in 1860, Buhnemann explains. “After recommending its use, hospitals began recording information and publishing their findings annually on why patients were admitted or their main reasons for death.” The forms were resurrected in the 1900s and an “11th version is currently being used to record pandemic cases”.

Beyond cleanliness and statistics, perhaps the most influential part of Nightingale’s legacy was the professionalisation and respect she brought to nursing. As we clap for the NHS and health workers on the front line, it’s hard to imagine nurses treated with anything other reverence. Before Nightingale gave it a favourable reputation, nursing was considered a lesser job for the lower classes, and nurses were generally considered as uneducated.

“Nightingale’s time in Crimea turned her into a celebrity and raised her profile to an extraordinary level, to the point where Queen Victoria was probably the only person who was more famous than her,” Bates says. News of her time in Turkey made headlines back home, the image of the lady with the lamp turning her into a national icon.

Above all, Nightingale was known for being strong-willed and did not scare easily. “She didn’t make a lot of friends among the doctors at Scutari, as they weren’t used to working alongside a woman and Florence was someone who rarely accepted ‘no’ for an answer,” Buhnemann explains. Nightingale was also devout, believing she’d been put on Earth by God to help the vulnerable.

With her new image came great influence. Donations poured into the Nightingale Fund, which was established in 1855, and by 1859 stood at £45,000 (roughly £2.6m today). This was used to establish the Nightingale Training School at St Thomas’ Hospital, which opened 9 July 1860. Nurses from both institutions took positions all around the world. Even today, the Florence Nightingale Foundation continues to fund the training of nurses.

More than a century after her death at the age of 90, Nightingale’s legacy is still very much alive. The Nightingale Pledge, a modified version of the Hippocratic Oath, has been recited at some nursing ceremonies since 1883; the Florence Nightingale Medal has been given out by the Red Cross every two years since 1912. When the Nightingale Hospital opened in London earlier this year, Prince William described it as “a landmark in the history of the NHS”.

And if she was facing these dark times with us today? “She’d quite likely be in charge of things,” says Bates. “She’d probably be pushing for testing and trying to find out what proportion of the public have had the virus or still have it now – indeed she asked the government to do something similar for the 1861 census.

“Just like she ran the enquiry into the Crimean War, she’d be very interested in learning lessons and using this knowledge to implement policy. If she could see a way to save lives now or in the future, she wouldn’t relent until it was done.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks