‘I feel safer in China’: The international students fleeing the UK

Tens of thousands of Chinese students complete degrees in Britain every year, but fears for their safety amid the coronavirus pandemic have seen hundreds trying to get home, reports Emily Goddard

Memories of the past four years spent in Edinburgh come flooding back to Isaac Ma as he sits in his room packing the few belongings his bag can hold. The 22-year-old gives some of his possessions to a friend, but other things have to be thrown away. He is due to leave his shared flat in Newington in two days’ time to travel back to his native China – a trip he didn’t expect to have to make so soon.

Tens of thousands of Chinese students complete degrees in the UK every year, but fears for their safety amid the coronavirus pandemic have seen hundreds fleeing to return home.

“I’ve had loads of experiences and memories,” Ma, a final-year economics student at the University of Edinburgh, says. “I haven’t had any time to say goodbye to all of my friends. It’s sad.”

The day before, on 12 March, he had watched Boris Johnson deliver a speech following a meeting of the government’s Cobra committee. The World Health Organisation had declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic, and the prime minister advised those with symptoms, or the vulnerable and over-seventies, to self-isolate at home for seven days. “Guided by the science”, he stopped short of closing schools, banning major public events or telling people to stay at home. “It’s vital to remember to wash your hands … this country will get through this epidemic,” he concluded.

This country, however, was no longer where Ma felt safe. He booked a ticket home to the southwestern city of Chengdu immediately. “Sichuan province has a population of around 80 million, which is not too dissimilar to the whole of the UK, and the total infection number is around 580, but for the UK it’s far more,” he tells me. “In the UK, if you have slight symptoms you won’t get tested. The situation in the UK is definitely worse than the place I’m from. Because I have a chance to escape, of course I will.”

Finding the ticket was neither easy nor cheap – it cost £1,800, three times what Ma would usually pay out of season. The journey was longer too; instead of the typical 13 to 14 hour flight, this one would take 30, and see him travelling from Edinburgh to Frankfurt, then to Shanghai, before touching down in Chengdu.

There was also a risk he would not make it through each of the connections and be sent back to the UK. “I have mixed feelings,” he tells me the day before flying. “I’m relaxed because I’m going to get out of the situation here, but I’m still anxious because of the strict rules for passengers. There’s still a chance I could get denied from Germany and have to come back to the UK or get infected. I’m still anxious about that.”

Ma is one of hundreds of international students attempting to leave the UK because of fears over the government’s response to the pandemic. “Out of all the Chinese students I know, more than 50 per cent are leaving or planning to leave,” Ma says. “I’m in a group chat of people planning to go home and sharing the information about how to get through the journey. There are about 340 people in the group.”

Wendy Gai, like Ma, was compelled to go home after watching Johnson’s address. “I realised the NHS would not be able to offer medical help – people with symptoms like fever or coughing will not be tested – and can only stay home to self-recover,” says the 21-year-old, who is in her final year of a modern languages degree at Edinburgh. She fears that what happened in northern Italy and Hubei will happen in the UK too.

Gai paid four times the usual price to travel home to Shandong, a province near Beijing. She also noticed that just the day after she secured her ticket all flights leaving for China within 10 days were sold out.

Other international students want to travel home but are yet to book a flight. Luyu Feng is 22 years old and is a final-year anthropology and media student at Goldsmiths, University of London. She plans to fly home to the eastern province of Zhejiang in May. “When I learned of the second case of people dying of coronavirus in the UK I knew I had to go home,” she says. “In China, the reaction is more effective compared with the UK, in my opinion. In January and February, I was really concerned about my family at home, but now my dad completely understands what I was feeling back then. For now, I’ll lock myself down and concentrate on my work – then I will have a smaller chance of getting infected.”

We were passing by where there was a newsstand. Somebody picked up a newspaper with a coronavirus front page, looked at me and said, ‘Oh, coronavirus everywhere’

Feng, like Ma, is in a WeChat group of almost 500 mostly Chinese students from around the UK who are trying to get home – only this group is specifically for those working together to book a charter flight. “The title of the group chat translates basically to ‘Renting a jet, going back home’,” she says.

The exodus of international students has not gone unnoticed by staff at universities around the country. A lecturer from the department of media, communications and cultural studies at Goldsmiths, who wishes to remain anonymous, says all the international students on his course have either left or want to leave. Among them are those from China, France and Greece. “My class has fallen apart in the chaos of the last few weeks,” he says. “The assessment criteria all had to change because the work was practical and group-based. The international students have either left or are waiting for their flight because they couldn’t afford the first flights out after the crisis deepened and online learning was given the OK. They are understandably very anxious about being able to get back to their families.”

A tutor at Edinburgh who provides English language support and academic literacy for international students says all but one of his class – a Spanish student – have returned to their home countries, which include China, Chile, France, Japan and Sweden.

Dr Yinxuan Huang, a sociology research fellow at City, University of London, has been supporting Mandarin-speaking students at his Christian church and says he has not met a “single person who was not anxious”.

“We all are,” he adds. “Most of them spoke to me because they felt overwhelmed and depressed and could not take it anymore.”

However, Huang says he is not dissatisfied with the government’s handling of the pandemic, and applauds the financial aid available for workers and what he believes are rational, evidence-informed decisions. But most of his students don’t share these views. “I think most Chinese students believe the UK government is incompetent,” he explains. “More specifically, most of them would say the UK government should learn from the Chinese government who took much more drastic measures.”

Besides fears over safety, there is also growing concern about a wave of hate crimes against Chinese and Asian communities.

Several racist attacks have been reported in towns and cities across the country, including London, Birmingham, Southampton, Exeter and Hitchin. Nine hate crime cases against people of Asian descent have been recorded since January by West Midlands Police and a further six have been handled by forces in Devon and Cornwall. Meanwhile, a poll in February found that 14 per cent of Britons would avoid contact with people of Chinese origin or appearance because of coronavirus.

“There are many stories about students and other Chinese people being racially abused trending on Chinese social media (especially WeChat),” Huang tells me. “However, these stories have somehow framed the British society as a racist and xenophobic place, which obviously has elevated students’ level of fear. Maskaphobia is perhaps the most prominent example of these stories. Personally, I did hear two cases in which students were called at to ‘get the f*** out of here’ and ‘virus’, and one case in which a couple of students were shoved at a bus stop. All three cases were in London and all the students involved did wear masks.”

Feng says she has experienced some discrimination and, although she would not deem it severe, it made her feel uncomfortable and excluded. While in a supermarket, a woman question in a hostile manner why she was wearing a mask. “It’s like my skin colour affected her,” she says. “An Asian face plus a mask is not OK.” She and a friend were also targeted on the street. “We were passing by where there was a newsstand. Somebody picked up a newspaper with a coronavirus front page, looked at me and said, ‘Oh, coronavirus everywhere.’”

While other nationalities are also fleeing the UK, Huang believes the majority are from China. “My feeling is that Chinese students are quite divided – some really want to leave, the rest are determined to stay,” he explains.

British universities increasingly depend on tuition fee income from international students, and more Chinese students choose to come to the UK for their higher education than from any other nation. More than 120,000 Chinese people enrolled at universities in Britain in 2018-19, which translates to a rise of 34 per cent since 2014-15. The fees paid by these students totals about £1.7bn, or 5 per cent of total income.

Not all students have been successful at securing flights home as Ma, Feng and Huang. Many have had their flights cancelled, or struggled to find a ticket in the first place.

Zimo Wang, 20, from Guangdong, came to Edinburgh to study modern China in literature and film, and business English as part of an exchange programme, but decided to travel home early because of the outbreak. She booked a flight home – the price of which increased from £500 to £1,800 in five minutes – with Air France for 20 March, but it was cancelled. She then booked a second ticket with KLM for 12 April and that too was cancelled. “Every day they just decide to close more flights,” she says. “Very few of my Chinese friends successfully made it back home because lots of their flights are being cancelled just like mine.”

Wang, however, accepts that she will probably have to remain in the UK until the pandemic is brought under control. Until then, she is staying positive. Her home university, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, has also sent her a box of face masks. “I am doing very well in Edinburgh even with little hope of going back successfully,” she says. “I am learning French on Duolingo, and learning how to record and edit videos because I want to be a vlogger in the future, and I read a lot. So my day is full and happy. Even though I felt confused about many of Boris’s attitudes and policies to deal with this virus, I am confident in the great British people to conquer it. So I am not that worried because I know sooner or later there will be a flight that won’t be cancelled and could take me home. I am not anxious about that.”

Wang is among hundreds of thousands of students, both from the UK and abroad, who remain stuck at university campuses across the country since the lockdown came into force on 23 March. Estimates from the sector suggest around 350,000 could be stranded.

Universities UK says institutions expected this and have been planning for several weeks to accommodate them. “Different universities will have different challenges, but a key consideration will be how to ensure that students in accommodation are safe, well and fed,” a spokesperson from the advocacy organisation adds. It will mean, in some cases, students being moved from their normal accommodation to an alternative location where it’s easier for the university to ensure they are looked after.”

Isaac Ma touched down in Chengdu on 16 March after what he describes as the most memorable journey of his life. “I have a lot of travel experience, but this one was extremely special,” he says.

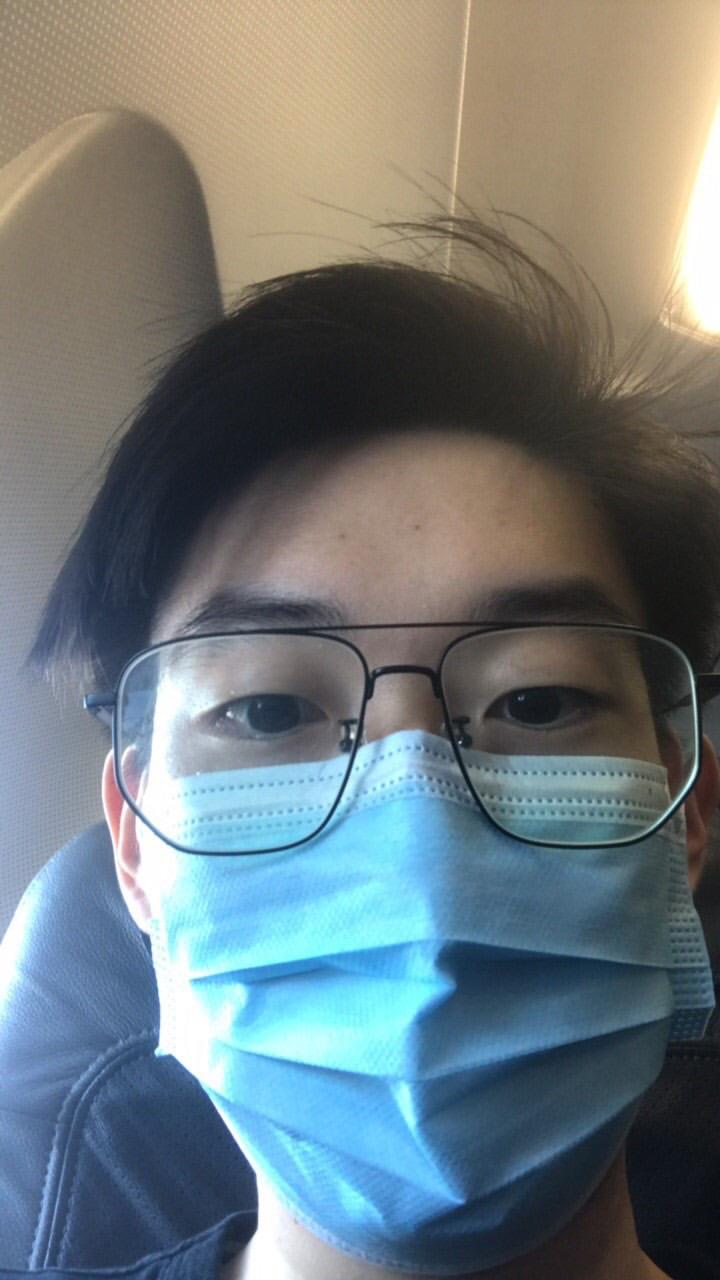

Ma approached the journey with extreme caution to reduce the risk of contracting the virus. On the first leg of his journey to Frankfurt, he and all the Asian people, including Koreans, on board were wearing masks. “But only 10 per cent Europeans had masks on,” he says.

Beyond Frankfurt, Ma added goggles to his protective equipment and put on a high-grade FFP2 mask. “I changed them every six hours,” he explains. “People all looked funny in their protective outfits. But everyone at least had their masks including all Europeans travelling to China.” He also chose not to eat any of the pre-packed snacks provided on the flight, only sipping water occasionally through a straw.

Ma spent four-and-a-half hours on the plane after landing in Shanghai because of strict rules in place at airports to prevent further spread of the virus. He watched as people travelling from Italy and Iran left the plane to get tested.

He knew, however, that even once off the plane in Shanghai there might be setbacks. At the time, people arriving back into China were immediately checked by health officials and their temperature taken. If anyone within three rows had a high temperature it would mean immediate quarantine for 14 days. A normal temperature would mean further questions about their recent travel history and, if given the OK, travel on to their next destination – in Ma’s case, home to Chengdu. That last bit of the journey would require 14 days of self-isolation.

For Ma, that meant 24 hours in a hotel chosen by the authorities in Chengdu while he awaited the results of his test for coronavirus. On 18 March he learned the test came back negative. He was moved on to another hotel in the city staffed by people in hazmat suits and protective equipment for the remainder of the 14 days. “There is someone who takes the night shift, sitting in the corridor for the whole night,” he explains. “They really are doing a lot for us. I’m living here like a normal hotel guest. They are nurses, clinicians, they don’t usually do those things like sending meals and taking out trash.”

He was not allowed to leave his room on the eighth floor but was able to order food from local businesses – these too were delivered by staff in hazmat suits – and his first choice was a nostalgic bento box. “It’s what I usually ate back in high school. I just want to feel the memories again.”

“Just boarded Air China flight to Beijing! (Cabin crew extra, extra warm ‘welcome home!’) Never thought I’ll finalise my undergraduate journey and leave Edinburgh in such a way,” Wendy Gai wrote on Twitter as she got on the plane in Frankfurt to begin the last leg of her journey on 15 March.

But then things took a starkly different turn. She tested positive for coronavirus and was immediately hospitalised in Beijing. She describes experiencing difficulty breathing. “Over the past days I was resting because I was so tired,” she says. “Nurses and doctors were coming in and out to do all kinds of medical checks. Hopefully, I’ll be able to be back home in a few weeks.”

Going back home will only be possible once Gai has two consecutive tests that come back with a negative result. She has since had two further tests, one on 22 March and another on Saturday (28 March) – both were positive.

She posts photos of her view from the hospital bed and tells me she is “feeling better” but is still being given oxygen. “Third week here already. Now eagerly wishing to get back to the normal routine, to enjoy reading, speaking, sunshine, staying with the family and visiting Disneyland with friends. Life has always been much more wonderful than I imagined.”

At the dining table in their Dujiangyan apartment, Ma and his father celebrate their reunion with a supper of double-cooked pork stir-fry – one of the most famous dishes in Sichuan cuisine, alongside hotpot. The weather is beautiful and Ma plans to climb nearby Mount Qingcheng after taking a walk with his father. “It feels so good to move my legs,” he says. “The air is perfect.”

Although he is home, Ma’s journey is far from over, particularly where his education is concerned. More travelling lies ahead and a return to the UK is on the horizon – when the coronavirus pandemic is under control.

He has applied to study for master’s degrees in finance and economics at University College London, LSE and King’s College. He already has one conditional offer and is confident of securing the place with his undergraduate results, even though that degree is ending in a way he could never have expected. “I will be upset not to graduate with my friends in Edinburgh,” Ma says, “but it’s just a ceremony, right? I am satisfied with the situation because I’m still healthy and living.”

He wonders if this pragmatic attitude comes from knowing this is not the definitive end of his life in Britain. “I know I’m going to see those places at least one last time and if I pursue my degree further, I will have even more opportunities. I have a friend who isn’t going to do a masters in the UK next year. He definitely looks sadder than me. I can imagine how he really wants our graduation ceremony.

“Twenty-twenty is a fairly crazy year. We all have experienced many things that can rarely happen. Let’s hope all the worst things can pass through our lives quickly.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks