Revived and renamed ... Debut novels are anything but these days

The publishing world loves a debut author. But is too much emphasis put on the ‘next big thing’ at the expense of building careers? And are Bame writers missing out? David Barnett reports

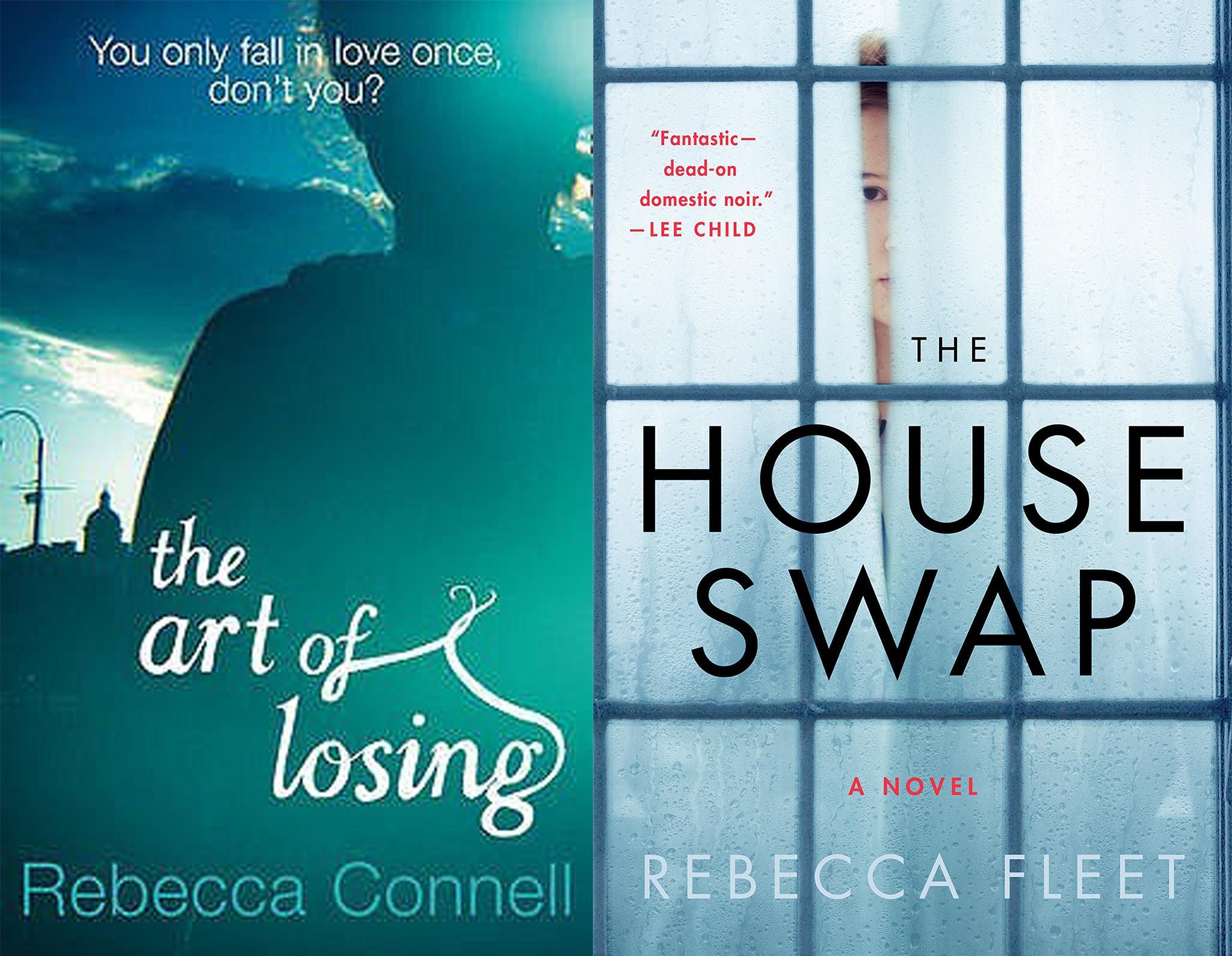

In 2018, Rebecca Fleet published her first novel, a gothically tinged psychological thriller called The House Swap. It received rave reviews and was the subject of a healthy marketing push by her publishers, Transworld, an imprint of Penguin. On its website, Penguin says that Fleet lives and works in London and that The House Swap is her debut thriller, with another, The Second Wife, to follow in August this year.

When news of Fleet’s two-book deal was announced in The Bookseller in 2017, Frankie Gray, Transworld’s commercial fiction publishing director, talked of the publishing house’s excitement to “launch a standout new voice with all the focus and dedication she deserves”. In an interview Fleet did with crime fiction website Dead Good Books, The House Swap was hailed as “an exciting new thriller by [a] debut author”. American trade magazine Publishers Weekly noted that “British author Fleet makes her US debut with a consummately plotted” first book.

The key word here, of course, is “debut”, flagged up in most of the marketing and reviews. Except, it wasn’t the author’s first book at all. Her debut novel was The Art of Losing, published in 2009 under her real name Rebecca Connell. She tells me “it got pretty much no attention”, which might have been true from a sales point of view. However, it was widely and warmly reviewed, with the Guardian calling it “a heartfelt examination of betrayal and guilt”, the Financial Times saying it was a “confident debut”.

A second novel, Told In Silence, followed in 2010 (“which got even less attention”) before Rebecca —now married with the surname Cormack — decided to switch genres to the hugely popular domestic noir market of female-led thrillers. She says: “My agent was very firm that we sent my last book out under a new name and pitched it as a :debut psychological thriller”. Editors knew I had been published before but no more detail than that.”

But why the apparent subterfuge? When Rebecca got her two-book deal as debut author Rebecca Fleet, it had been eight years since the publication of The Art of Losing. Would readers care that she was now writing in a different genre, even if they remembered that book and its follow-up?

Well, readers might not but the book retail industry has a much longer memory. It’s quite common for authors who decide to write in a different genre from what they start off in to adopt a pen name, or subtly alter their byline. It isn’t designed to pull the wool over readers’ eyes, but rather to fool the algorithms. I have been a debut author, by my reckoning, three times. First as novelist and short story writer David Barnett, then as the writer of a steampunk fantasy trilogy and finally as David M Barnett, author of ”commercial fiction”.

Anyone who had read my earlier fiction barely noticed the new initial. But that didn’t really matter anyway. What mattered was that when the chain bookstores were asked to stock my new book, they would put my name into their computers and “David M Barnett” would appear to be a brand new author who had never published a book before.

Why was this important? Because had the booksellers inputted “David Barnett” they would have seen that his previous novels did not exactly set the world on fire in sales terms. They might have ordered my new book based on what they sold of my previous ones… or not ordered it at all. But David M Barnett was a different matter, a new thing, untested, untried, but with the push of a big publishing company. David M Barnett was for all intents and purposes a debut novelist.

If there’s one thing the publishing industry loves, it’s a debut author. The book fair calendar has obviously been seriously curtailed this year, but they’re generally typified by publishers from across the world gathering in a feeding frenzy of deals. And top of the menu is usually debuts. Sharks thrashing about for new blood is the wrong analogy. It’s perhaps more focused and calculated than that. Maybe a crowded table in a casino would be a better image. “Publishing is about gambling, fundamentally,” agrees literary agent Juliet Mushens of Mushens Entertainment. “With debuts there’s a big risk, but there’s also the possibility of a major gain – you have a blank canvas, no sales track record, nothing to ‘overcome’ in terms of obstacles.”

Were this just an internal industry matter, a case of taking on blank-slate authors to maximise sales, it’s unlikely anyone would care about it. But the industry does publicly put debut authors on a pedestal… and not everyone is convinced that “new” automatically means “better”. Joanne Harris is the author of 24 novels, including fantasy novels, ghost stories, children’s books, even a Dr Who novella. But she is best known for her 1999 novel Chocolat, which was made into a movie and propelled her to superstardom. Harris has rarely been out of the bestseller lists ever since.

Which is sort of her point when she expresses disquiet about what she perceives as the publishing industry’s obsession with debut novelists; Chocolat was her third published novel.

As a hugely successful author, Harris often gets sent early proof copies of forthcoming books in the hope that she’ll offer a pithy endorsement for the front cover. However, she’s noticed something about a lot of the books she’s been receiving of late. “What they’ve been doing recently is they have been repackaging old authors or at least experienced authors – as debut authors,” says Harris. “An author changes publisher and the new publisher pushes them as a debut. I’ve had several proofs recently pushing books as debuts that aren’t debuts.”

The book industry has always thrived on comparisons. If you loved X, you’ll adore Y. Amazon recommends books based on what other people who have read the same books as you have also bought. Readers know what they like, in other words. Which means, suggests Harris, that the industry’s love affair with debut authors is almost counterintuitive.

An author changes publisher and the new publisher pushes them as a debut. I’ve had several proofs recently pushing books as debuts that aren’t debuts

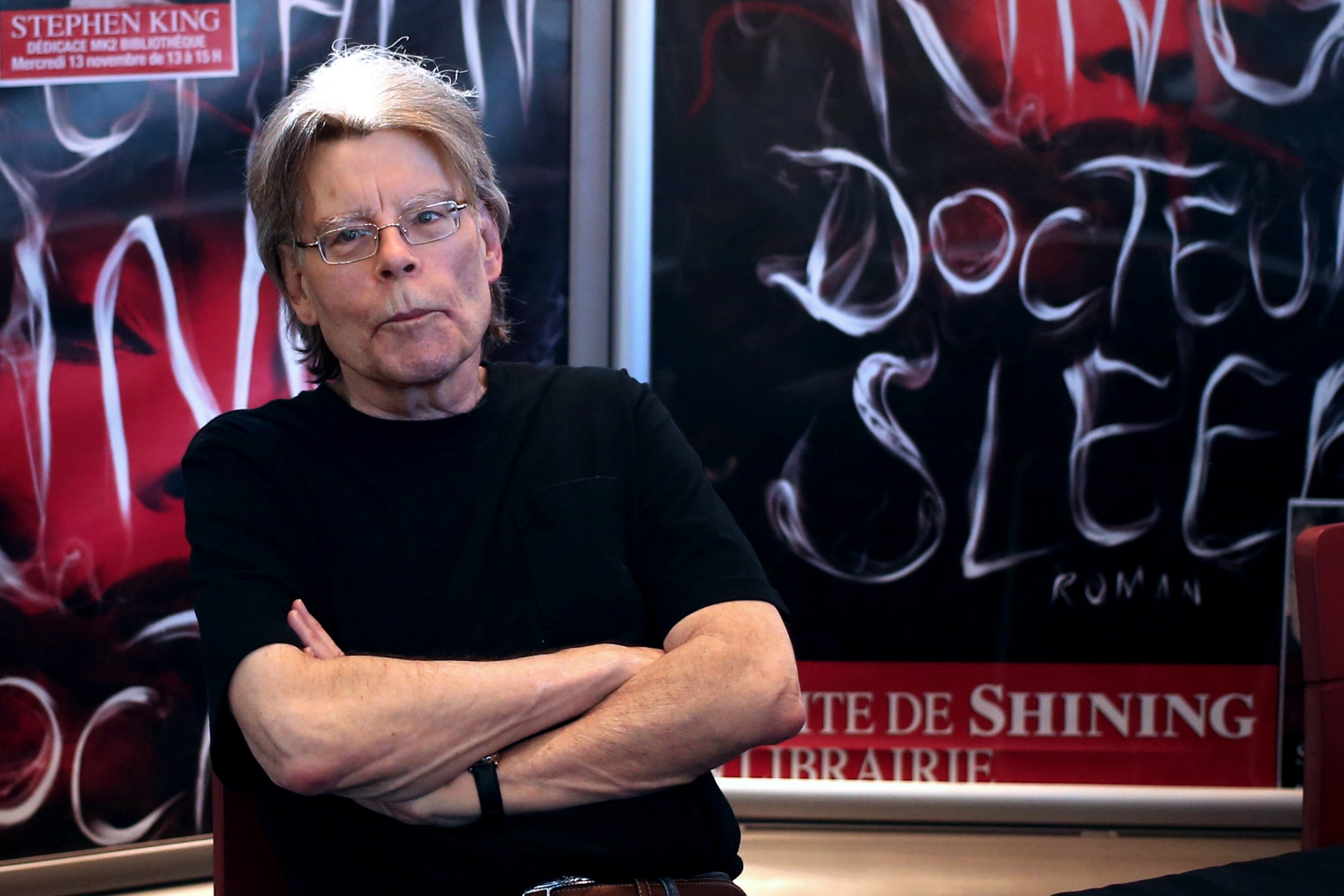

She says: “You’d think what would happen with books is that it would be quite hard to get a debut to sell. People like to go with what they already know. If they like Marian Keyes they will buy the new Marian Keyes, if they like Stephen King they will go looking for the next Stephen King. And the way you used to sell a debut was to tell readers, hey if you liked Marian Keyes this author is just like her but she’s new and she’s like the new Marian Keyes. But they don’t do that any more instead they package commercial new authors – and they’re often young authors – and they sell them as debuts, as a brand new thing.”

But… why should this be a problem? “I love it that new authors are getting a chance,” stresses Harris. “I would like it to be, however, a chance to build a career rather than just get a big push as a debut and then be forgotten because publishers are chasing the next debut.

“Sometimes, and particularly when you’re talking about young authors, a writer can be completely taken aback by the attention and the scrutiny and the money that can come with a big-value push, and then just be abandoned. The publishers seem to just hope that the next book will sell itself and when that doesn’t happen because sales and marketing have not put the effort in they assume that the second book is no good and then the young novelist is just left hanging.

"I’ve had several young novelists tell me that’s what happened to them and that is concerning because it seems to me that any publisher with any sense should be helping them to build their career rather than making a fuss of them when they’re 21 and then hoping that they’ll just manage when they’re 22 and 23.

“That doesn’t happen so you’re getting people with very confused expectations as to what publishing is going to give them. It seems to me that they’re elevated because they’re new and there will always be somebody younger, somebody newer. It doesn’t seem to me a good way to run a business. Quite apart from the established authors who may have been with the publisher for years and who are watching all this in confusion.”

The American author Heather Demetrios published on Medium a piece called “How To Lose A Third Of A Million Dollars Without Really Trying”, which gained quite a lot of traction last September. Demetrios detailed her experiences of getting published, starting off with quite a large advance, and how nobody told her that this wasn’t what necessarily would happen with every book. After a whirlwind of Manhattan apartments and cocktails, Demetrios had blown most of her money and discovered that — now she was no longer a feted debut author — there weren’t any more payouts of that size forthcoming.

Harris says: “That’s quite a common story, and one a lot of people will recognise. It’s important not to take for granted if you get one big advance you will get an equally big or a bigger one… that probably won’t happen because the novelty factor has gone. Like the guy who wants trophy women, some publishers want trophy authors.

If those bright, new authors are going to sustain a career they are, as Sharmaine Lovegrove suggests, going to have to get a lot more savvy about the business of publishing

So is “debut author” really shorthand for “young, beautiful and marketable?” Mushens doesn’t feel youth is necessarily a factor. She says: “A debut basically just means an author with no market footprint. I don’t think conflating young authors with debut authors is necessarily helpful. I sold a debut novel by a 70-year-old author a few years ago, and it sold in 26 languages around the world! It’s not fair to make it about age, as a debut can be any age.”

But Harris certainly thinks there’s a problem with diversity in publishing, and that is reflected in the types of authors who are pushed as the next big thing. “Mostly I think what it means is white and straight and of a certain background,” she says bluntly, “because those tend to be the ones that get spotlighted most often. It’s not all debut authors getting attention, it’s a few selected debut authors, and perhaps not always the right ones.”

With the recent Black Lives Matters protests in the wake of the death of George Floyd in the US, there has been a concerted effort from publishers and agents to actively seek out voices from the Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic communities. This has been welcomed in some quarters, but condemned in others as paying lip service to something that should have been done a long time ago.

As the publisher of Dialogue Books, the Little, Brown imprint which she set up in 2017 to bring out books from under-represented voices, diversity is pretty much Sharmaine Lovegrove’s watchword. “I totally agree with the assertion that there’s a particular kind of white, middle-class, woman debut author who gets a load of attention,” says Lovegrove.

As a publisher, Lovegrove knows any business needs new blood. “It’s about something fresh and different while you’re waiting for your existing writers to write. It can sometimes take between two and five years to write a book and it’s really important that we’re always looking for new talent while we’re waiting, so I don’t think it’s an odd thing… you would never say to a gallery please don’t take on any new artists and you wouldn’t say to a cinema don’t show films made by new directors.”

Lovegrove is adamant that it’s not a case of abandoning authors once they’ve made their debuts. “There’s an extra push that’s done with a debut because you’re basically elbowing space for a new author. When they have their second book out that groundwork has been done but there’s another set of tasks.”

However, she does think that authors could do a little more to help themselves; specifically, getting to know the business of publishing. “People are desperate to get published but naive not to understand how the whole thing works.”

Given that so much effort goes into launching debut authors on to the market, you’d expect that there must be a strong appetite for them among the book buying public. But is that really the case? Do readers especially seek out debuts? Are they more valued than an author on their second, fifth or tenth book? Tracy Fenton is the founder of The Book Club on Facebook, which has more than 9,000 members, and blogs about books at Compulsive Readers. Does she take special notice that a book is by a debut author?

“No, not really. I am only ever interested in the description of the book. If the blurb and description sounds like something I want to read then I don’t care if it’s written by a debut or an established author who’s written 30 books.”

“Which is 100 per cent how it should be,” says Lovegrove. In fact, readers are perhaps more loyal to established authors than the focus on new authors might suggest. This is especially true in the science fiction/fantasy genres, says Mushens.

Readers will always have their favourite authors, and will buy their books come what may. Mushens points out that many best-selling authors have “broken out” partway through their careers… she cites Our House, which was Louise Doughty’s 12th novel, Sarah Perry’s Essex Serpent, which was her second. “And Jojo Moyes famously wrote Me Before You while out of contract, which sold millions of copies worldwide.”

The publishing industry’s infatuation with debut novelists doesn’t look like slowing down any time soon, whether readers care about it one way or the other. If those bright, new authors are going to sustain a career they are, as Lovegrove suggests, going to have to get a lot more savvy about the business of publishing. And perhaps that will manifest — like the proof copies that land on Joanne Harris’s desk, like Rebecca Fleet, like myself — in more and more writers playing the publishing game and constantly reinventing themselves as the new fresh thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks