‘What have people been getting up to during lockdown?’ Sex during the Covid-19 pandemic

Despite social distancing rules, GP Berenice Langdon has seen an increase in the number of patients coming in with sexually transmitted infections. So what’s been going on?

I am looking at someone’s genitals. I can see five or six blisters scattered over the area each surrounded by redness. “A lovely, lovely classic rash.” Actually I don’t say this out loud, only in my head. I have learnt through bitter experience that remarks like this don’t go down well with patients.

In fact, I say, “Yes. I can see the blisters very clearly. Let’s take some swabs to double check what it is.”

I know exactly what it is. It’s obviously genital herpes. The new partner, the timing, the symptoms as well as the rash all fit together to make the diagnosis super-clear – which is why I am so enthusiastic. The truth is I don’t usually get to see a lot of classical genital herpes rashes. In normal times patients go straight to the sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinics and I rarely see them.

But recently patients have been on a sort of merry-go-round when it comes to appointments. Where GPs are busy with people suffering (or dying) from delayed surgery and delayed outpatient appointments, ordinary GP patients, unable to get through, are ending up in long queues outside of A&E. And where STI walk-in clinics have been shut, young people have been coming in to see their GPs.

Anyway, I’ve recently diagnosed a lot more genital warts and herpes than usual. I’ve also got to know the local genital urinary medicine (GUM) consultant rather better than I ever expected to, especially when it comes to guidelines on wart paint.

Because I am seeing more sexual infections than usual, it has set me wondering. Has the lockdown reduced the number of sexual partners people have and reduced the amount of sexual infection circulating? Or has the opposite happened? Has the reduction in face-to-face appointments patients have experienced during the past year led to a surge of undiagnosed sexual infections? It’s difficult to know for sure but there are now some early figures being published as each country begins to collate the data for 2020 on sexual infections.

Seeing someone with an STI during the height of lockdown is at first glance a bit weird. Aren’t we all meant to be on our own and in our own rooms? How did these latter-day romancers meet anyone when all socialising was supposedly stopped? How did they negotiate that ever-changing fence of rules and persuade their new acquaintance to break them? They would have had to transgress literally every single one, from no travelling and the two-metre rule to no indoor socialising and the ultimate no “hugging”.

At the start of the lockdown I think there must have been a sort of fantasy among STI specialists and GPs (or maybe it was just me) that this was it. This was the firewall that was going to stop chlamydia and all the other STIs in their tracks and reduce rates of sexual infections once and for all.

Early data supported this. In the US, The American Journal of Preventative Medicinenoted that the number of chlamydia diagnoses dropped by 50 per cent in the first surge of March-June 2020 compared to the preceding months.

It was working. People must have been having fewer partners. Or were they? What have people been getting up to during lockdown?

It’s often difficult to draw generalisations with regards to sexual habits. But one thing is clear: whether the pandemic affected peoples sex lives or not, it certainly did not affect scientists researching sexuality during this time.

In contrast, stable couples who were not living together in some cases struggled to keep their sex lives going. Many turned to telecommunication for help

A massive 377 articles just in English and originating from the western world have been written on this topic, according to a review published in January 2021. From this, clear themes surface, in particular that co-habiting couples across the board had less sex. Research in many different European countries including Poland, Britain and Italy have all come to the same unsurprising conclusion, that many felt a lack of desire due to stress. Although some, about 10 per cent, had more sex than usual, immediately illustrating the difficulty with research like this.

Fascinatingly, this has been borne out in the UK fertility rates for 2020. The report from the Office of National Statistics shows that the birth rate in December and January of 2020 shows a steep decrease compared to the previous year, indicating that fewer babies were conceived than usual during the first lockdown, which fits with the evidence that cohabiting couples had less sex.

In contrast, stable couples who were not living together in some cases struggled to keep their sex lives going. Many turned to telecommunication for help, as with every other aspect of our lives recently, making use of the internet, sexting and webcams to stay connected.

But for single people, the group I am most interested in, life has been tough. Traffic to porn sites registered a measurable increase of 11.6 per cent during this time and the researchers note a detectable surge of porn use in the mornings when people would normally have been commuting to work. According to a study in Australia during the initial lockdown, 7.8 per cent of singletons reported sex with a casual hook-up compared to 31.4 per cent in a normal year. A study in the UK picked up a similar rate; 9.9 per cent, but when analysed for age, 17.7 per cent of young people aged 18-24 had what the study termed “intimate physical contact outside the household”.

Another study, this time based in Israel on men who have sex with men, revealed that despite restrictions 40 per cent of the group studied had still gone on and met a new casual sex partner during the lockdown period.

Overall, then, it would appear that both couples and singletons had less sex or fewer partners but that a substantial minority continued meeting new partners in spite of the various lockdown rules in different countries.

But does this slight overall reduction in new partners explain the 50 per cent drop in chlamydia diagnoses reported in America? Not in the slightest.

In fact, this drop could not reflect a true drop in prevalence even if sexual practices changed overnight. We know this because the drop happened too soon. The American paper assumes reasonably that “sexual practices likely were unaffected until after the declaration of the national emergency on March 13, 2020”. We know chlamydia takes time to replicate – it has an incubation time of two to eight days – and it also takes time for it to begin to show symptoms such as discharge, about three to six weeks. A real drop in cases would not be seen for several weeks after the start of the US lockdown. But the drop registered started to happen within days.

It is likely that the reduction in cases simply reflects the reduced medical care available. Telephone-only appointments, testing only offered to those with symptoms (missing those in high-risk groups without symptoms) and encouragement not to leave the house meant that the number of tests done reduced by 60 per cent, closely aligned to that 50 per cent drop in diagnoses. This means that in the first six months of the pandemic, an estimated 150,000 in the US were undiagnosed.

This situation is closely aligned to the UK data, recently published by Public Health England (PHE) this month, titled “Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England”.

The document notes that there was a 25 per cent overall decrease in tests done, and consequent to this, a 32 per cent decrease in STI diagnoses, not dissimilar to the American experience. Therefore, although over 300,000 infections were picked up, there were potentially 150,000 undiagnosed cases over 12 months.

Personally, I am delighted to look after people who have sexual infections. I have a deep interest infectious disease and I am happy to see anyone who manages to get an appointment with me

Chlamydia diagnoses in particular dropped by 30 per cent, but genital herpes, which has to be diagnosed clinically, dropped by much more, 40 per cent. Again, this implies undiagnosed cases rather than a reduction. Public Health England probably have not realised about the increased numbers of herpes diagnosed in general practice.

Although the document is specific, the BBC seems to think it’s a good news story. Its headline reads misleadingly, “Sexually transmitted infections fall during pandemic”, rather than a more cautious but less exciting headline which perhaps should have read, “Sexually transmitted infection diagnoses have fallen during the pandemic probably because people can’t get appointments”.

The PHE report concludes that although community surveys suggest that fewer people reported meeting new sex partners in 2020, a substantial proportion still had ongoing risks for STIs such as condomless sex with new partners. This, combined with the continued high levels of gonorrhoea and chlamydia detected, has led to sustained spread in the community.

Luckily, we have the National Chlamydia Screening Programme in this country (running since 2008) so hopefully this will help reduce these potentially high levels of undiagnosed infections circulating right now in the community. Or will it? Because it turns out PHE thinks that 2021 is a good year to cut down this programme. Although there are higher levels of infection in men, it wishes to screen only women.

Until now the routine has been to screen all young people annually, male and female. But from now it will be just females, on the grounds that their health is the most affected. It is well known that undiagnosed chlamydia infection can lead to infertility in women, which is why screening and early treatment with antibiotics is the gold standard. PHE concludes that this approach is therefore more medically effective as well as more cost-effective.

However, only 51 per cent of those involved in the public consultation agreed that this was true. Respondents expressed their concern that the proposed changes would increase the burden of responsibility for all young people’s health on young women. They also felt that young men’s role and responsibility in achieving good sexual health would be undermined.

PHE has pushed ahead with the cuts to screenings anyway.

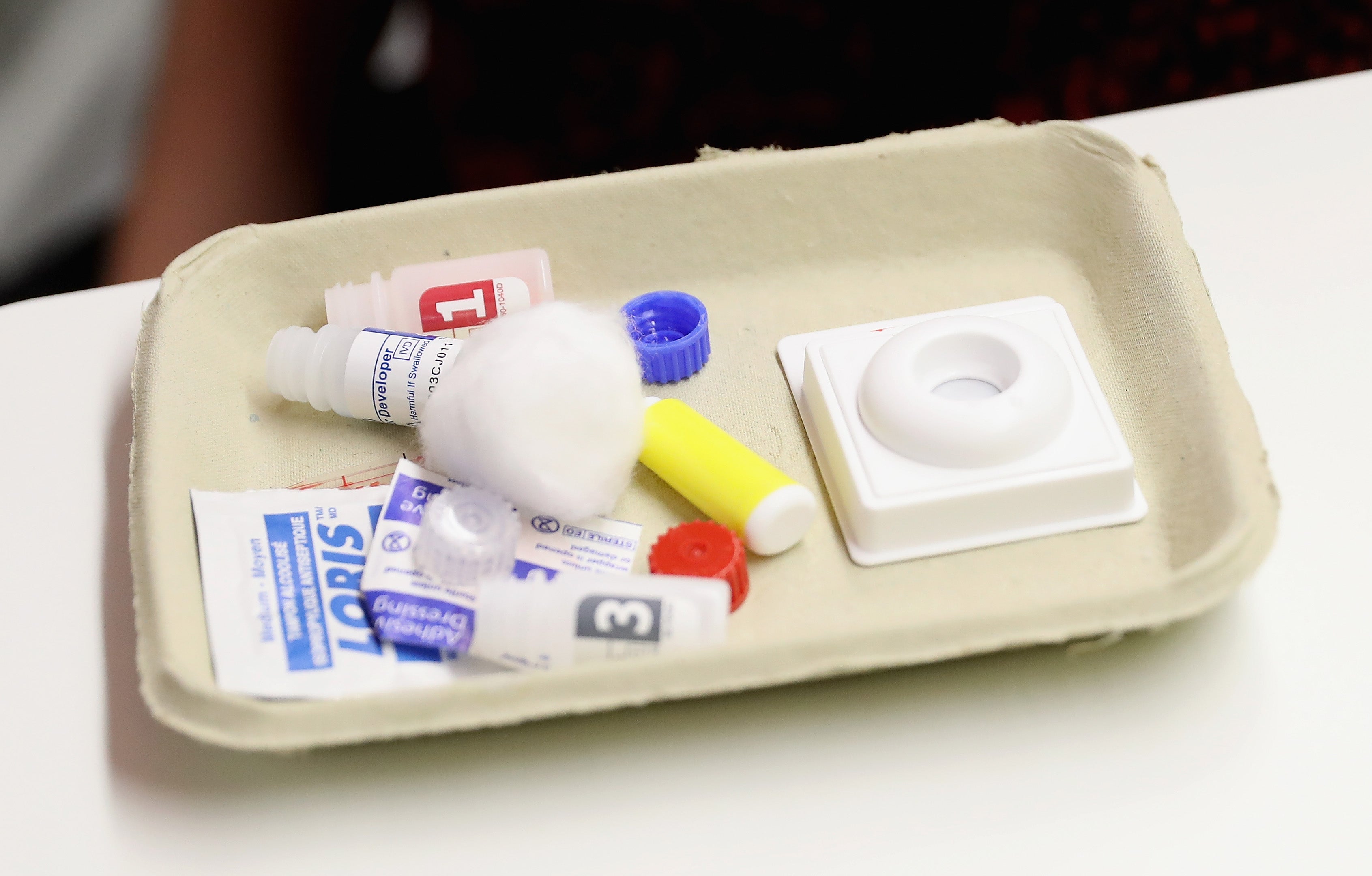

What about my patient’s rash? What action do I take? After carefully breaking the news that it might be genital herpes, I send swabs to check for other infections such as chlamydia and gonorrhoea, I give written information and explain about avoiding sex while symptomatic. Finally, I strongly advise using condoms with new partners in the future. I also seize the opportunity to tell the patient about online NHS sites that can post condoms or STI swabs straight to them.

Have GPs been landed with the responsibility of STIs because walk-in sexual health clinics have not fully reopened? Well, yes, a bit perhaps, but even in normal times GPs share this responsibility with the sexual health clinics. There is a lot of overlap between the two specialities.

Personally, I am delighted to look after people who have sexual infections. I have a deep interest in infectious disease and I am happy to see anyone who manages to get an appointment with me. But that’s the difficulty with sexual health: the appointments. The patients seen are often young people or people wary of approaching healthcare workers. They have to be attracted in with easy to access care such as walk-in clinics, absolute confidentiality – even from their GPs – friendly notices on the walls and free condoms. Ringing at 8am on the dot to get a GP appointment and waiting 20th in the line for 40 minutes (or longer, I know, I’ve done it) is not going to encourage a young person to get checked.

What we have now is the perfect storm for sexually transmitted infections. Thousands of potentially undiagnosed STIs, reduced walk-in clinics, a lack of face-to-face appointments in general practice and a drastically reduced national chlamydia screening programme, combined with the full reopening of pubs, clubs, concerts and universities leading to a flowering of new sexual partners. Instead of the magical reduction in sexual infections I imagined, we may well have to contend with the exact opposite, an explosion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks