Does Friday 13th fill you with fear or is it just another day?

Do you count magpies? Are you afraid of walking under a ladder? And what happens if you put new shoes on a table. Today is Friday the 13th and David Barnett is looking into the meaning and origin of superstition

It’s Friday the 13th, and we all know what that means: a whole pile of bad luck. But why? Well, that’s really a two-part question, beginning with why Friday the 13th should be deemed any less lucky a day than Thursday the 12th or Saturday the 14th. In fact, we can drill down even further and look at why the number 13 is bad news. My street, for example, doesn’t have a house between numbers 11 and 15 – at least, not one that is visible to the mortal eye. Many tower blocks don’t have a 13th floor, a lot of hotels don’t have a room 13.

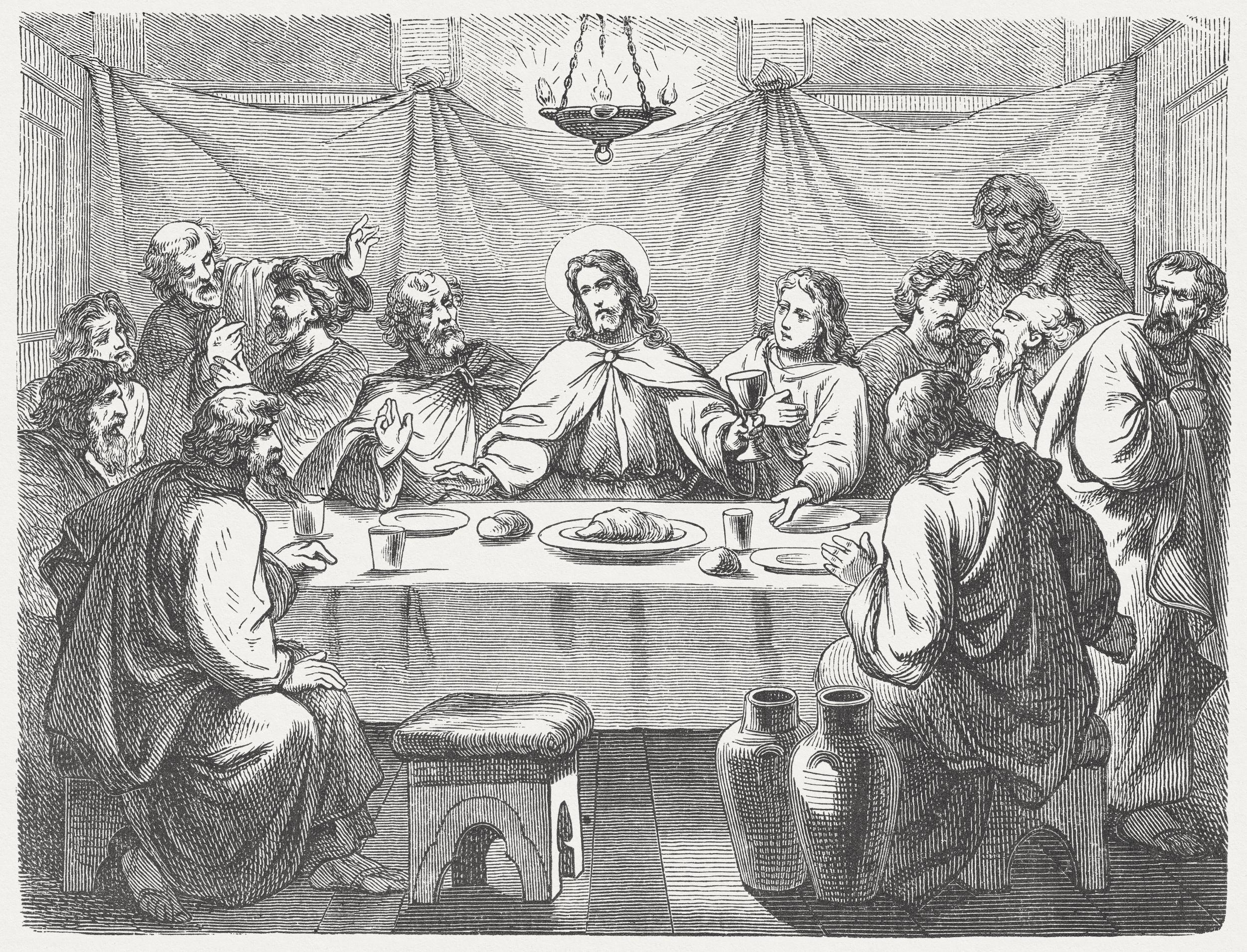

Triskaidekophobia is the scientific name for anyone suffering an irrational fear of the number 13, and a lot of it is thought to relate to the fact that at the Last Supper there were 13 people seated around the table, and the 13th was Judas, who went on to betray Jesus.

Jesus, of course, was crucified on Good Friday, but it seems that it wasn’t until the 19th century that Friday falling on the 13th of the month – which it does at least once a year, will do twice in 2020, and did three times in 2015 – was considered to be a bad omen.

The Judas theory is one possible explanation for why Friday the 13th is thought to be a date loaded with portents. But the real question is, why do we, in our enlightened, technological times, still attach any weight to it? Why are we superstitious at all, in the year 2020

Friday the 13th is thought to be a date loaded with portents. But the real question is why do we attach any weight to it? Why are we superstitious at all, in the year 2020?

I ask Dr Nicola Lasikiewicz, senior lecturer in the School of Psychology at the University of Chester, what exactly superstition is from a psychological standpoint. She says: “Superstition is a subset of paranormal belief, which is belief in scientifically unsubstantiated phenomena, such as extrasensory perception, apparitions and poltergeists to name but a few. Superstition is the belief in causal links between action and outcome, such as carrying a lucky charm to evoke good luck or not walking under a ladder to avoid bad luck, when no such causation exists.”

No causation, in other words, no logical or rational reason for it. But that doesn’t stop people being, to one degree or another, superstitious.

Take Teresa, 43, who lives in the west of Ireland. She’s a librarian and has four children. She is, by her own admission, highly superstitious. “Friday the 13th?” she says. “We’re all relieved when we get through one of those unscathed… aren’t we?”

I throw some other popular superstitions at Teresa. Walking under a ladder? “No, thank you!” Putting new shoes on a table? “Bad luck!” Spilling salt? “Bad luck! Counteract it by throwing a pinch backwards over your left shoulder.” Breaking a mirror? “Seven years’ bad luck!” Opening an umbrella inside the house? “That means it will surely rain!”

Speaking of rain, one way to ward that off on your wedding day is to hide a Child of Prague figurine under a hedge the night before. At least, according to Teresa. Did she do that? “Yes, I did that.” Did it work? “Well, it didn’t rain!”

There is, of course, not a whit of science in any of this. Does anyone really believe that opening an umbrella indoors or hiding a figurine in a hedge can materially affect meteorological conditions? Dr Lasikiewicz agrees. “By definition, paranormal beliefs are beliefs in scientifically unsubstantiated phenomena, and within this, superstition involves applying cause and effect between objects or behaviours when no such link exists or could even be possible.

“So, by its very nature, there is no scientific evidence for this. However, some research, including my own, looks more at the effect this can have on people, whether positive or negative and this can, of course, be supported by evidence.”

According to Dr Lasikiewicz, the origins of many of our superstitions might have actually been in attempts to make the god-fearing masses more pliable.

Crossing fingers is a near-universal sign of wishing for something, but it’s thought that crossing fingers was also a secret way for Christians to recognise each other when Christianity was illegal

She says: “Interestingly, the word superstition may derive from the Latin superstitio, meaning ‘to stand over in awe’. A lot of superstitious beliefs are rooted in religion, perhaps as a means to encourage the congregation to adhere to the faith or to provide a means of comfort and control during times of uncertainty

“For example, crossing fingers is a near-universal sign of wishing for something, but it’s thought that crossing fingers was also a secret way for Christians to recognise each other when Christianity was illegal.

“One explanation for why four-leaf clovers are perceived as lucky is that when Adam and Eve were evicted from the Garden of Eden, Eve stole a four-leaf clover as a token of remembrance of her days in Paradise.

“One of my favourites concerns spilling salt. Many will toss a pinch of salt over their left shoulder to ward off bad luck. This is based on the suggestion that the devil is always standing behind you, and throwing salt in his eye distracts him from causing trouble. However, this may also be an unlucky omen designed to prevent the waste of what was an expensive commodity!”

Like me, Teresa will routinely wave or salute a lone magpie, to fend off the sorrow it’s said to bring, according to the old rhyme. While, as Dr Lasikiewicz says, there might be religious origins to many superstitions, it does feel as though many of them are rooted in a more folklorish, non-church soil. Especially for Teresa, growing up in Ireland, who inherited many of her superstitious beliefs from her mother. She says: “My mother calls a superstition a piseog [pronounced pish-oag] or an old wives’ tale. I’ve always loved the word piseog. It has a magical ring to it, for me anyway. Funnily enough though, people often use those terms to dismiss superstitions. They’ll be preceded with the phrase ‘that’s just a…’.

“There’s part of me that wonders how it is that I give any credence to superstitions. I consider myself quite rational and practical most of the time and I feel like being superstitious contradicts that.

“We live in a society where everything requires concrete evidence to be considered factual by the majority and believing in all of these things can often be ridiculed. A lot of superstitions are grounded in fear though and fear can prompt resistance, I suppose. So, as far as I’m concerned, the ‘non-believers’ are welcome to take their chances and live a superstition-free life but I’ll stick with my ‘just in case’ habits. Each to their own, as the Mammy always says!”

Curiously, Teresa’s sister Caroline, a little older than her and works as a pharmacy technician. Despite the sisters (and their six siblings) all growing up together with a mother who Teresa describes as “the most superstitious person I know, bless her”, Caroline has absolutely no truck with any of it.

“I don’t even think about things like that, to be honest,” says Caroline, who says she would be more than happy to, say, walk underneath a ladder. “I find it all a bit mad! It’s just not where my brain would go. I don’t think I’d say I’m generally more logical or rational than them but definitely when it comes to the superstitions I feel I am. I’ve told them I’ll have them committed yet!”

Dr Lasikiewicz says: “There are many different possible sources of paranormal and superstitious belief. Sociocultural factors are one possible source. These include the various customs, lifestyles, or values that characterise a society or group.

“Possible sources include parents, peers, society, culture, the media. By process of internalisation, children can, effectively, absorb the beliefs of their parents. This is also seen in religion. But, there are many other factors to consider which may facilitate or counter such beliefs, for example, peers, education, the media. Other theories suggest that belief in the paranormal and superstition can stem from early life experiences, how we process information, creativity and reasoning, personality, education amongst many others.”

For Teresa, being superstitious is a habit that’s hard, or even impossible, to break. She says: “It’s been part of my behaviour for so long that it has definitely become automatic. I do believe it to a certain extent though, some of them more than others. The salt spilling is a big one for me!

“If something bad or unlucky happens and I haven’t observed the rules, as you say, I would be pretty convinced that’s why.

“I find I can be intolerant with myself too, as in sometimes I’ll have a word with myself and tell myself to stop being so ridiculous. That doesn’t always stop me though. No matter how much I tell myself it’s all nonsense, I still have the fear of invoking bad luck if I don’t observe the rules!”

No matter how much I tell myself it’s all nonsense, I still have the fear of invoking bad luck if I don’t observe the rules!

And she’s not alone as there seems no sign of rationality taking over from deeply-held superstitious beliefs. Dr Lasikiewicz has done much research in this area. She says: “Yes, superstitious belief and thinking is still prevalent. Athletes and sports people are renowned for their superstitious rituals before important competitions or games. Some students still take lucky charms into exams, and people wish each other good luck almost every day.

“Some people are superstitious due to it being consistent with how they think the world works (their worldview), some because of religion, some because it is part of their culture or social group, for example, belief in black cats, broken mirrors bringing bad luck and Friday 13th are socially shared.

“Other superstitious belief stems from our own experiences, for example, performing well on an exam while carrying a lucky charm. Another explanation centres on superstition being learned. JB Skinner conducted now famous experiments on pigeons in which he conditioned them to act in a superstitious way (for example, performing a full turn) in order to receive a food reward.

“Based on my own research in the area, facing challenge, stressors or uncertainty can also increase superstitious thinking. We know that, in general, paranormal belief often increases in times of stress or challenge.“Paranormal beliefs, including superstitious beliefs may, therefore, be needs-serving and reflect a form of coping characterised by more avoidant and emotion focused strategies. Psychological stress may, therefore, activate latent beliefs in an attempt to gain control over seemingly uncontrollable events.”

There are, says Dr Lasikiewicz, two sorts of superstitions – socially shared superstitions, for example, magpies and black cats, which she says are the most common form of superstitious belief, but this is closely followed by idiosyncratic, personal superstitious beliefs. These are formed out of our own personal experiences of good or bad luck and often include the use of lucky charms or specific rituals, for example, before going into an exam or interview, or competing in sports.

Teresa’s list goes on and on. “Lift both feet when driving over a railway track – gets tricky when you’re the one driving! If you have an itchy nose you are about to have an argument with someone. If your left hand is itchy, you’re coming into money – you have to scratch the itch on wood for it to transpire, though. If you make a wish don’t share it with anyone else or it won’t come true.”

She knows that her superstitions are irrational. When I ask her if there are any of them that she observes that she wishes she could ignore, she says: “All of them! They can take up quite a bit of time and effort!”

What of Dr Lasikiewicz? Given her extensive research into the psychology of superstitions, surely she cannot adhere to any of these irrational beliefs? “Good question!” she says. “Just like your other interviewees, I grew up with a mother who is extremely superstitious and for a time, some of that rubbed off on me too.

“However, my scientific training has called time on many of those beliefs. Am I still superstitious? Well, I do admit to wishing people good luck, and I have, on occasion, counted magpies, but to be honest it’s irrelevant.

“As a scientist, it is my job to try to remain objective and base conclusions on evidence. Further, there is some evidence that researcher bias can influence the outcomes of experiments on things like superstition and paranormal belief and so it is important to avoid this.”

Still, it’s Friday the 13th and all that, so whether you’ll be saluting magpies today or think it’s all a load of old tosh… mind how you go.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks