Remote working: What the UK’s last lighthouse keepers can teach us about isolation

If there is anyone that knows what it’s like to spend long periods of time alone, it’s lighthouse keepers. Serena Coady gets advice from former custodians about how to weather the loneliness of the pandemic

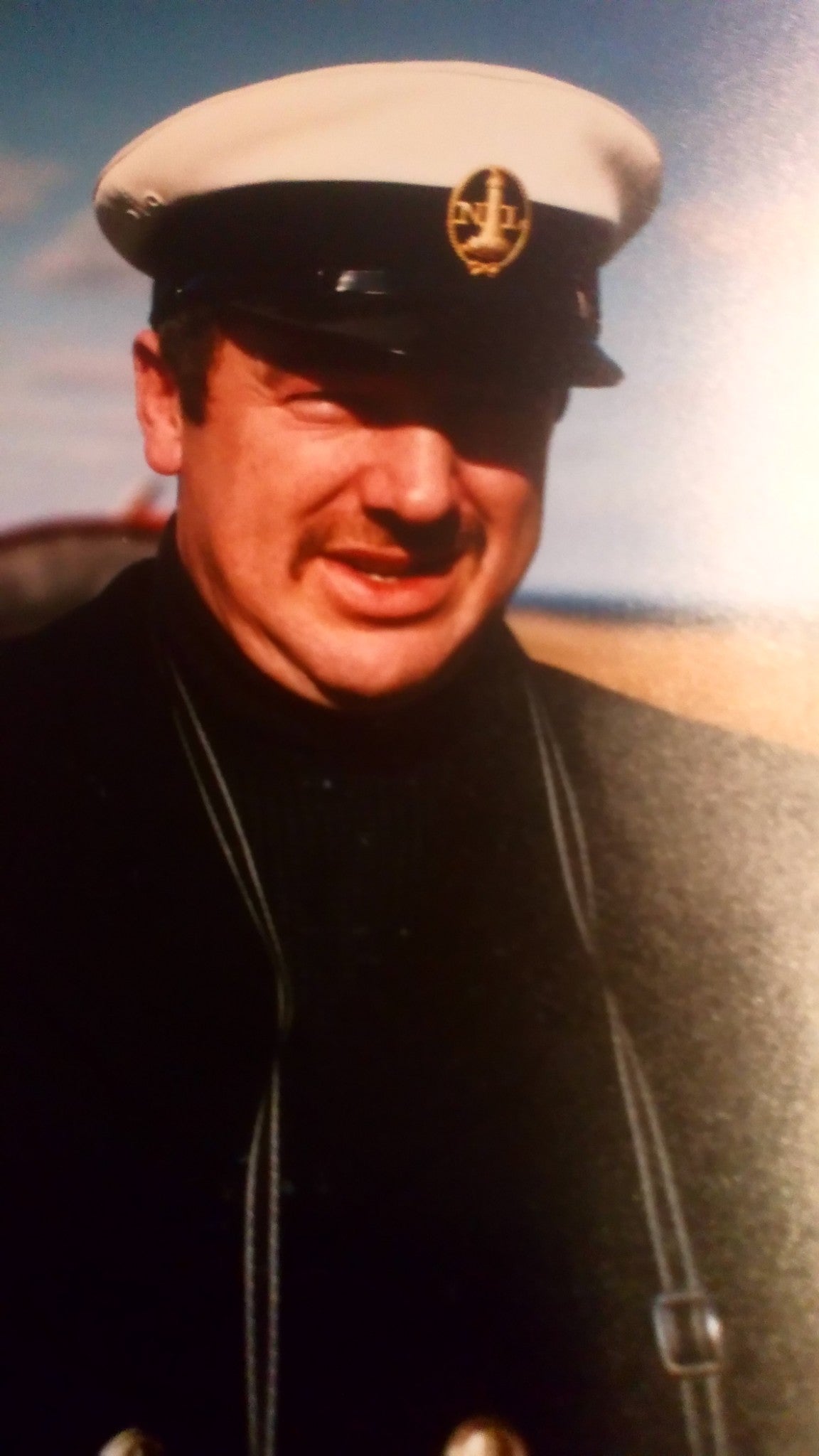

It’s 1976. Neil Hargreaves is 28 years old and already familiar with the rigours of isolation. He doesn't know that one day, millions of people will be in a situation similar to his. He doesn't know that making sourdough and exercising in front of a screen, 1984 style, will become the pinnacle of leisure. However, he knows the ache of being away from loved ones and the joy of finding a good book. As the former keeper of one of the UK’s most remote lighthouses, his work has been a unique training ground for lockdown. Only with more elemental havoc.

Twenty miles west of Marloes Peninsula lies the Smalls Reef, a volcanic bedrock ridge where tidal rapids generate violent rips. Being stationed here as a first-time keeper was like being a junior doctor during a global pandemic. It was the job at its most extreme. “At the Smalls, the sea could come right over the lighthouse. You would get a total blackout, then it would all wash down again and daylight would return. You would feel the lighthouse shudder, but it was built to last. I was more scared when I worked on the trawlers. The boat once rolled near Iceland and half of it was submerged in water. So, when it came to lockdown, I was sort of used to isolation. On tower rocks, you couldn’t leave when the seas were washing over the landing,” says Hargreaves. He spent two years at the rocky outpost, 28 days on, 28 days off. In preparation, he attended a six-week course that covered radio signals, first aid, weather reading and bread making.

In 1772, 26-year-old violin maker Henry Whiteside was tasked with designing a lighthouse that would help mariners navigate around the Smalls. The appointment was not a success. Scottish lighthouse engineer Robert Stevenson later referred to Whiteside’s beacon as “a raft of timber rudely put together”. It weathered years of environmental beatings until it was replaced with a granite lighthouse in 1861, the second tallest in Wales.

The Smalls was said to conjure “strong feelings of isolation” and “a significant sense of openness, remoteness and exposure”. On Google Maps, you will need to zoom out six times to see anything other than dark stretches of the Atlantic. The nearest landmass is Grassholm, the coconut-topped black rice pudding of tiny islands. During breeding season, the basalt is covered with 39,000 northern gannets and their droppings, a stark contrast to the solitary lighthouse. “Before 1801, there were only two keepers at the Smalls. Then one of them died. The other one, who didn’t want to be seen as having bumped him off, kept the body. It began to smell so he tied it to the gallery rail outside. Relief was overdue and by the time it arrived, he’d lost his sanity,” says Hargreaves. So protocol changed and three became the magic number.

The first recorded lighthouse dates back to the Ptolemaic Kingdom, however, the development of modern lighthouses took place during the 18th century. In the UK, the expansion of transatlantic trade routes triggered the need for a network of beacons. The new structures were robust and fully exposed to the sea due to advances in structural engineering and construction materials. During the late 1960s, lighthouses were gradually being automated. For the trusty human illuminators, it was the beginning of the end. Keepers were offered redundancies – Hargreaves accepted one during the first round in 1988 – and in 1998, the UK’s last keeper switched on the lights for the final time. Hargreaves says it was the best job he ever had.

Unlike the original wooden beacon, morbid curiosity about the 1801 incident at the Smalls still holds strong. In the past decade, the tale has inspired a radio play and two films. After widespread automation, lighthouses and the lives of its residents continue to capture our imagination. Lighthouses feature widely in literature, serving as a historical setting to explore moral detachment (The Light Between Oceans) and the duality of security and peril (Pharricide). Tales of insanity and paintings depicting lighthouses at the ends of the Earth have forged a mythos around the desolation and necessity of these structures. For many of us, lighthouses are a striking visualisation of one of our earliest fears: being completely alone.

For Hargreaves, the Smalls was not as melancholic as art would have us believe. “Nobody was truly on their own at the Smalls. You had the two others. You were only alone during the middle watch while the others slept.” Besides, the keepers assigned to the lighthouse made for interesting company. Among their ranks were a former police officer, butcher and postman, each bringing unique skills.

Lighthouses facilitated a kind of hobby exchange. “Most keepers had hobbies. It was important for wellbeing. There was a real range of them, it was surprising. Some were painters, one of them was so good he was regularly commissioned. Others were into photography, birdwatching, crocheting, knitting and kite fishing. I must admit I did quite a lot of reading. I preferred factual books.” Images of evenings spent crocheting a woollen hat for a soon-to-be-born niece present a soothing alternative to the usual tales of misery and madness. One former lighthouse keeper, Gordon Medlicott, became so proficient in knitting, embroidery and cross-stitch that he became a centrefold in a specialist cross-stitch magazine.

Most of Scotland’s coastline is wild, rugged and difficult for mariners to navigate. So Ian Duff was born in the right place. Between 1976 and 1992, the lighthouse enthusiast manned 13 lighthouses throughout Scotland. Like Hargreaves, he knows the slow joy of giving small ships a glass bottle home. “When I began, I couldn’t fit a ship in the bottle, but I learned. Some keepers made lamps out of shells and sometimes we played cards after lunch before one of us went to bed or went onto a watch,” says Duff.

He also spent time building a scale model of Skerryvore. Skerryvore – a name derived from the Gaelic words sgeir (rock) and mhor (big) – stands tall on an exposed reef 12 miles off the Isle of Tiree. The rocky outpost is reminiscent of Jean Guichard’s dramatic shot of La Jument. It was Duff’s main ambition to man Skerryvore, a lighthouse he considered to be Scotland’s most extraordinary station. He was stationed there for nearly five years.

Duff had worked in the whisky industry since leaving school, but after a downturn in 1975, he was made redundant. During this time, the lighthouse board was seeking “jack-of-all-trades” from remote areas, so he left the whisky business for a risky business. The job came with unpredictable weather, isolation and “poor pay” – he would earn in a month what he previously earned in a week – but he knew it was his cue to follow his boyhood dreams. He had been captivated by the lighthouse “way of life” since he was eight.

Duff was hardly ever lonely, even on remote stations like Skerryvore. But anxiety lingered. “You left your wife at home, went out for 28 days, and came back for 28 days. I always felt on edge leaving her. If anything went wrong at home, I wasn’t there to help. Sometimes when I was due to leave the lighthouse, the weather would get wild, and the helicopter couldn’t land. So you’d have to unpack your bag, make your bed up, and wait a couple of days for the weather to improve. There weren’t telephones at the lighthouses, so if you wanted to speak to your wife, it was through a complicated radio system. If something went wrong with the system, you couldn’t talk until the engineer came out.”

These days, correspondence comes easily to Duff. Though automation brought an end to their time in lighthouses, both Duff and Hargreaves still carry a torch with the Association of Lighthouse Keepers. During the pandemic, the group has hosted quizzes and talks over Zoom with former keepers and enthusiasts from around the UK. They recently opened up membership and had people from San Diego, Tasmania and New Zealand drop in.

Duff is 72 and still has his miniature model of Skerryvore. His hobbies are slightly different now: he doesn’t need to wait for another keeper to finish a shift or for the other to wake from an afternoon’s rest. Though lockdown has created a different sense of isolation, Duff gets to spend quality time with his new partner (his wife passed away a few years ago). During the first lockdown, they set upon the jigsaws, piecing them together, then glueing and framing them. He says it ensured their sanity. And yes, all the puzzles depicted lighthouses.

One drawback is that lockdown doesn’t offer many opportunities for paid puzzling. “One of the great things about being in a rock lighthouse is that once the wee jobs are done in the morning, the rest of the day was your own until you put the light on at night and ensured it kept revolving. So you were getting paid for your hobbies. It was an enjoyable way of life.” Some of the necessary tasks during the morning watch – 4am to midday – included performing a radio check with the coast guard, transmitting weather reports and washing down the steps.

With summer came certain employee perks, including uninterrupted sunset views and plenty of dry rocks to sunbathe on. But things took a sharp turn in winter. “At rock lighthouses, you’ve generally got to climb 30 feet to get in the door. Plus the sea comes round the base of the tower. Once October came, you were more or less incarcerated inside the tower till late March or early April. The sea was rough during winter. This is why these lighthouses are sometimes called ‘upright submarines’.”

Though the upright submarines were seasonal prisons, at least its residents could count down the days. “Being in a remote lighthouse, you knew that in one month you could have a break and get your freedom, whereas in this lockdown it’s sort of never-ending.”

For keepers, there was intention behind the isolation. It was a life they chose. David Appleby became a keeper at 21 and remained in the service for more than three decades. “Lighthouse isolation isn’t the same as our current lockdown. Keeping, of course, was your chosen occupation. The lighthouse was your home so you made the best of it and there were no other outside attractions, which differs from the enforced lockdown we’re in now,” says Appleby.

The 75-year-old was one of the UK’s last six lighthouse keepers. In the early days, he was stationed at Wolf Rock for two years. Situated between Land’s End and the Isles of Scilly, it was one of the more “notorious” lighthouses. Though he kept busy by reading, fishing and studying the natural environment, Wolf Rock was remote, difficult to relieve by boat, and limited in space. “I remember being stuck at the Wolf for three months because of sea conditions. Heavy southwest swell and waves swept over the lighthouse. The whole structure would shake and a whoomph-like sound or a loud bang like a sledgehammer was heard. We always looked forward to leaving and spending four weeks at home. It was something to anticipate – a ‘Where to next?!’ – unlike lockdown now. No one knows when it’s going to be over,” says Appleby.

As rogue waves made life beyond the beacon unsafe, the virus has kept many of us inside. Though we aren’t getting quite as thrashed by the weather, we share the same need to throw our imagination, our attention, at whatever we can find inside our four walls.

Turning to hobbies, as the keepers did for decades at sea, might not seem like a particularly new idea. The relationship between hobbies and mental health has been long-established. However, in these unique times of isolation, the need for hobbies is heightened. In a recent UK study, researchers analysed 55, 204 adults across 11 weeks of lockdown and found that increased time spent on hobbies such as reading, listening to music and gardening were associated with a decrease in anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Perhaps we could see lockdown as our own watch: 28 days at sea, 28 days on land. A time to nurture hobbies and explore new ones, like Hargreaves with his small, glass-bound boats, or a time to maintain a healthy anticipation, like Appleby. Our leisurely pursuits might not win us coverage in cross-stitch magazines, nor is there a guarantee we’ll be free in one month’s time, but it might make us better, happier people for when we return to land, or life as we knew it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks