Will Britain remain a global power?

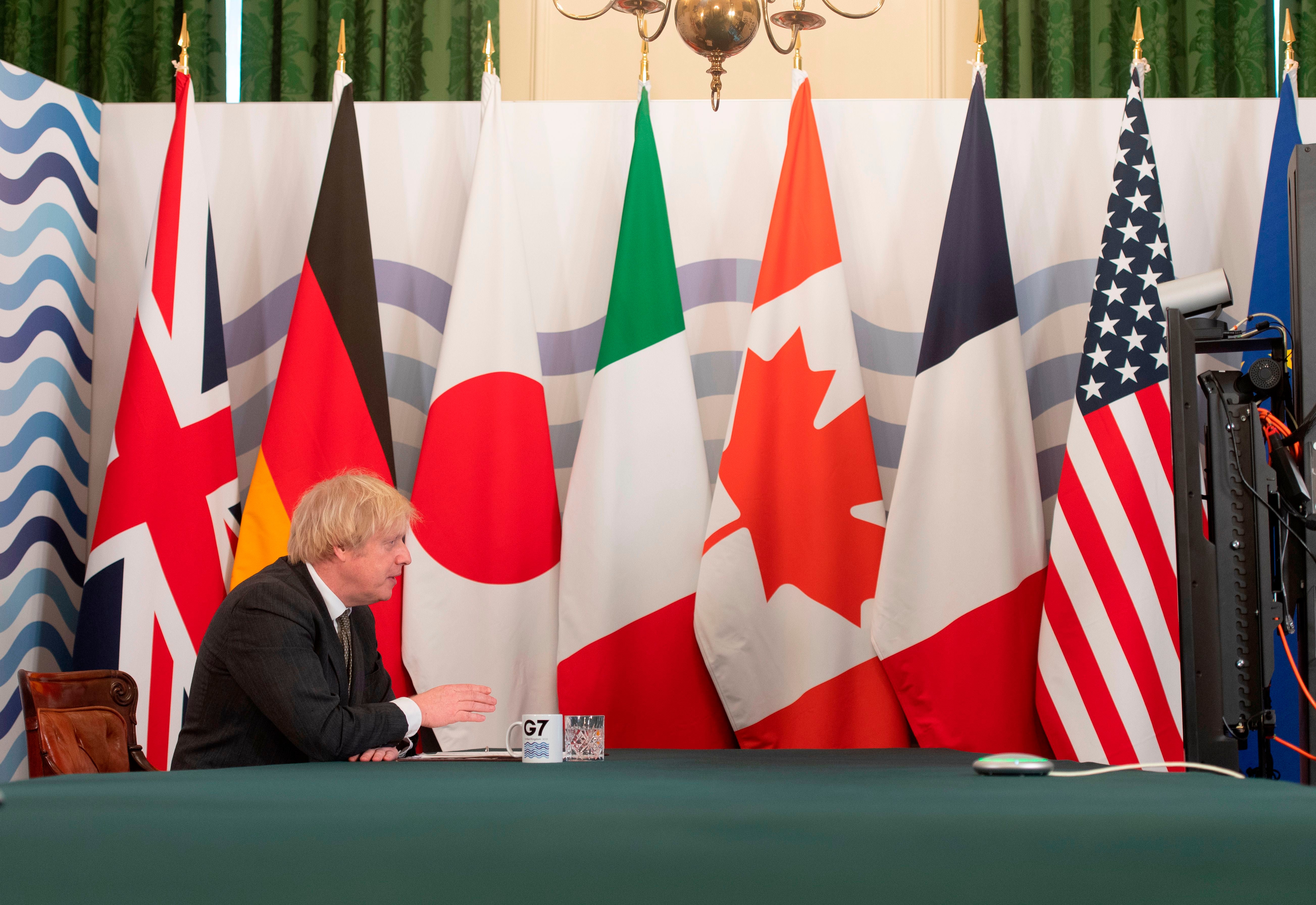

Boris Johnson may be enjoying the limelight as the success of Britain’s vaccine rollout continues but do not mistake this for any further influence or power on the world stage, writes Sean O’Grady

Apart from the welcome spirit of internationalism, the announcement that Britain’s forthcoming “surplus” of Covid vaccines will be distributed to developing countries is significant in other ways. Given that the vaccination programme is not yet complete, although proceeding smoothly, it seems premature to be distributing doses that do not yet exist. The only pressing need to announce such a thing would seem to be the imminent (next Friday) G7 summit in Washington. Britain, post-Brexit, needs to demonstrate that it has a role in the world, and the rapid “world-beating” vaccine rollout provides an irresistible temptation to indulge in “vaccine diplomacy”.

Like China and Russia, but pointedly unlike the European Union, Britain can also be seen to be able to win friends and influence people globally, and save lives into the bargain. Recent spats between London and Brussels over vaccine supply probably made shipments from the UK to Europe politically impossible. The vaccines are headed for villages in Malawi rather than Bavaria, and it is difficult to argue it should be the other way around.

So Britain, in the personage of Boris Johnson, wants to strut its stuff on the world stage. It is probably inevitable that a post-imperial power that retains its “Global Britain” mindset should crave to be seen to still count for something. The UK will host the COP26 climate change conference in Glasgow in November, having hosted June’s G7 in Cornwall. Liz Truss, the international trade secretary, is busily trying to get Britain into the Trans-Pacific Partnership and win trade deals with emerging powers such as India. Britain has resumed its individual seat at the World Trade Organisation, and is establishing itself as the lead in mapping the DNA of coronavirus variants.

On one reading, then Britain, newly divorced, is back on the global dating scene. On another, though, this medium-sized European power has probably never been less powerful or relevant, thanks to Brexit and the unstoppable rise of other powers, most obviously China. Isolation is more likely than being mobbed by suitors.

For the past few decades the British were able to claim, slightly conceitedly but with some justification, that the country “punches above its weight” in international affairs. The UK, uniquely, sat at the centre of many valuable concentric circles. There was the transatlantic “special relationship” with America, including sharing nuclear weaponry; Nato; permanent membership of the UN Security Council; the “Five Eyes” intelligence network (with the US, Australia, Canada and New Zealand); the Commonwealth; a historic role in and continuing links to the Middle East; and, of course, a lead role in the biggest trading bloc in the world, the European Union. No one else ticked all of those boxes, and British diplomats made the most of it. Only the home football teams let the side down.

Formally being at the centre of that geopolitical Euler diagram remains the case, with the obvious exception of the EU. But Brexit has meant that the UK is now less useful to the US, Japan and, arguably, the Commonwealth outside the EU than when it acted as a like-minded political, investment and trading “bridge” into the European pillar of Nato and the EU single market. That was less true under the Trump administration, but President Biden and his team have made no secret that they think Brexit was a great all-round blunder.

In practical terms things now cut both ways. The UK is faster to apply sanctions to Belarus, for example, but no one thinks that Minsk or Moscow cares much about little Britain compared to Germany and the EU, with vastly greater economic heft. The UK’s special interests from Hong Kong to the Falklands and Gibraltar could always be better protected by being able to call upon the network of alliances so painstakingly assembled since the 1970s. The same goes for Russian interference and assassination missions, Chinese trade abuses and the challenges of climate change and nuclear proliferation.

And the government seems less keen than its predecessors on projecting “soft power” via the BBC (which it looks like wrecking), and artistes working in Europe. The cut in the international development budget and the abolition of the Department for International Development didn’t say much for any pretensions to British moral leadership or caring about the world’s poorest countries (all of which possess a vote at the UN).

A longer-term threat to Britain’s international clout, and its status in the G7 and the UN, arises from relative industrial and economic decline. If post-Brexit economic growth proves sluggish, and Scotland and Northern Ireland leave the union (lopping about 10 per cent off GDP), then the UK will slide further down the international GDP league table. Brazil, Japan or the EU, for example, might have a better claim on a permanent seat at the security council; while India is already a larger economy than the UK, allowing for the vagaries of exchange rates. You can see where things might be going.

Such adjustments will not come immediately for Britain, but it is possible, at the least, that the old pattern of genteel relative decline will be resumed and Britain’s punches become ever more feeble. By 2030, say, a senescent Britain will no longer be able to exercise much influence let alone power in the world. Global Britain may not amount to much beyond a quaint tourist attraction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks