Scenes from an unholy war: Mass murder in Algeria

April 1995: When Robert Fisk is handed barbarous photo album he feels growing need to thumb through the pictures and then, the greatest shock of all, a kind of boredom as the butchery becomes routine

In the Algerian ministry of interior, Djamel Bouzenat hands me a leather briefcase, real leather with heavy pouches and steel clips and, stuffed into the deepest pocket, a heavy, plastic-bound album with the words The Barbarity of Terrorism printed in black on the cover.

He watches me as I open the book. He is waiting to see if I recoil from the contents. He wants to know if I understand the message these pictures are intended to convey. There are three snapshots on each page: a decaying, naked corpse with protruding teeth and a dark mess round the neck; the body of a middle-aged man lying in the dirt, still in his jacket and tie – the tie neatly tucked into a sweater – with another stain round his throat; a much younger man with ants’ tracks of blood spreading from his nose and mouth. All the pictures are in colour, so you can check the pallor of a man’s skin, the darkness of his blood, work out the minutes or days he lay dead before the snapshot was taken.

Sheikh Mohamed Bouslimani (the corpse with the protruding teeth) was photographed two months after he was kidnapped at Blida on 26 November 1993. The man in the jacket and tie (Mehdi Torki, murdered at Besbes on 2 January 1994) was freshly dead. The face with the tracks of blood was that of Amar Mouamia, less than 24 hours gone when his picture was taken at Guelma on 8 November last year. The photographs should overwhelm me with horror but after several pages a kind of appalled fascination takes hold of me. Here is the severed head of Yamina Benemara, a middle-aged woman whose head was cut off with a knife – or a saw – at Es-Senia near Oran on 11 April last year. The eyes are closed, the mouth slightly parted to reveal a perfect set of upper dentures, a thin tide of blood around the neck. The head is lying on some kind of mortuary table, like that of Mohamed Djaadoudi, killed at the same place on the same date, eyes shut fast, as if sleeping, thick dark hair still neatly combed as if he might suddenly wake up, separated from his torso, and start chatting to me like a character in a horror movie.

For Mr Bouzenat’s album is a horror show, a classic piece of pornography under plain, expensive cover. When you thumb through the pages, you find yourself glancing over your shoulder to make sure no one is watching – which, of course, in the Algerian ministry of interior, they are. As with all pornography, there’s a growing need to thumb through the pictures and then, the greatest shock of all, a kind of boredom as the butchery becomes routine, page after page of it, a sense of banality that increases even as the pictures become more terrible. Nabila Rezki is still beautiful, in her late teens perhaps, her throat cut open on 23 July last year, long, frizzy dark hair, sensitive eyelids, a gentle snub nose and that terrible, glutinous mass around her neck. There are pages of snapshots of 12 ex-Yugoslavs murdered in Medea in December 1993, one young man’s face in a grimace of pain, eyes wide with horror, throat hacked open so deeply that you can see his backbone. A French couple lie on the mortuary tiles, the woman with her clothes torn, almost bare-breasted, shot through the head and thorax.

What primeval energy produces such sadism? Not the fire of anti-colonialism, because, albeit at terrible cost, the Algerians won their war against the French. Nor can such energy come from the despair of a land without resources, for Algeria, the tenth largest country in the world, stands on billions of dollars’ worth of oil and natural gas deposits. Certainly this is not the fury of religious conflict; Algerians are all Muslims, all members of the Sunni sect, Islam is the state religion, the national flag – carried with such courage by the mujahedin fighters in the 1954-62 war – contains the Islamic crescent. Algeria should not be breaking into Bosnian fragments. I should not be looking at this terrible picture book.

Tucked into a back-pouch of the same leather briefcase, I find – when I get back to the hotel, after the ministry men have watched my artificially bland reaction to the snapshots – a video-tape with the words Women: Victims of Terror in Algeria printed on the spine. I slide it guiltily into a tape-player. Fresh corpses, in nighties and morning clothes, all of them women, sometimes with their toenails torn out, repeated again and again; here the pornographer’s art is clear, the same shots of the same severed female heads on perpetual replay. The cassette blanks out to be replaced with tape of burned trains “and supermarkets, of male corpses and blood – bright red, crimson, black – and desecrated graves. The cassette has been made by an angry man, 53-year-old Ali Boukerbache, who runs a company called Media-TV; there are some professional touches, the page-turns of dead men that emerge out of the graveyards, the slow-motion grief of widows, the freeze-frame of a wounded woman.

It is a relief to turn off the video machine, to order room service at the Hotel St George, a bottle of fine Mashgara claret – for the old French vineyards still flourish during the Islamic insurrection – and a salad bathed in onions, all this during Ramadan. On Algerian state television, Rachida Hammadi is introducing the evening’s religious programmes, chic in a patterned scarf, a secularist whose sister Houria works in the same television station, one of the bright young women who have flowered on the dull, government- censored broadcasting apparatus of the old FLN. A police siren wails across the city; the midnight curfew is two hours away but few go out after dark. From the window, I can see the streets of downtown Algiers, bathed in perfect light, and the great monument to the million-and a-half dead of the independence war, its concrete wings taking flight above the floodlamps.

You might even believe, at this witching hour, in the old, corrupt, peaceful Algeria of the Seventies and early Eighties. If the streets are empty, they are at least clean. There are pigeons moving under the eaves of the old pied noir villa on the other side of the tennis courts. On my bed lies a copy of that day’s El-Moudjahid, the regime’s most subservient newspaper, its subtitle – “Revolution for the People, by the People” – a hopeless, irrelevant throwback to another, earlier insurrection in which few now believe. Down in the Maison de la Presse at Kouba, Mohamed Abderahmani is still editing El-Moudjahid, having pleaded in vain for police protection after one of his journalists, Ferhad Cherkit, was murdered in central Algiers. His morning’s front page headline – “Huge support for presidential elections” – is a figment of the imagination, a throwback to the old Soviet clone journalism that dominated Algerian intellectual life from 1962 to 1989.

No one believes there will be elections this year, not while the countryside is under the control of the Islamist insurgents, not while the capital itself is lost to the government, not while the slums of Eucalyptus, Bab el-Oued, Chateau Rouge, Climat de France, Kouba and the rest are no-go areas to all but the most heavily armed paramilitary police.

Yet the authorities, the pouvoir, the regime, the army – call it what you will – still believe in the Pravda system of public relations, of insisting that what you want to be true is true, of believing what is in the papers because they themselves wrote it.

It is an odd, unique phenomenon, this political schizophrenia of the educated, Francophone elite. Whenever I refer to “civil war” in a report from Algeria for The Independent, an official of the foreign ministry or the ministry of communications or the ministry of interior chastises me for my exaggeration. Can I not see that Algeria is calm, peaceful, that the population is merely waiting to resume the democratic path – once the authorities have dealt with the little problem of “terrorism”. Another package arrives at my hotel room, a great bundle of glossy files documenting the economic growth and development of Algeria, its gas and oil production, the expansion of Sonatrach, the state-owned hydrocarbons conglomerate. On the table beside my bed, I place the Sonatrach files next to the album of atrocity pictures.

It rains overnight, heavy showers that almost smother the isolated shots that can be heard from the city. In the morning, I drive to the Central Bank.

The lobby is decorated like the interior of a space-ship, all white and blue plastic with strange golden polystyrene knobs on the walls. This, I am supposed to believe, is the nerve centre of Algeria’s economic recovery, the powerhouse which will rocket this broken country into the 21st century with massive new foreign investment. Even the elevator is painted blue and white. “This was designed by one of our most famous Algerian artists,” an apparatchik says with pride, punching the button to the third floor. “He is one of the men whom the terrorists want to murder. They want to murder everything that is beautiful, artistic, free in our country.”

The receptionists have short skirts. You have to shake your head to remember where you are. In his leather-chaired office, Abdelouahab Keramane, the bald and jovial bank governor, sips coffee, explains the future convertibility of the Algerian dinar, the narrowing exchange rates between official and black market since the 40 per cent devaluation of 1994.

Mr Keramane is like a man completing a crossword inside a crashing airliner. Which is the real Algeria, I suddenly ask him: the air-conditioned Algeria of this office with the central bank governor in his gentle blue suit, explaining exchange rates and IMF loan conditions, or the Algeria outside the window where, only a few hours ago, I heard shooting?

The eight-year war with France remains a defining moment in Algerian as well as French history, a cruel and brutal search for national identity as well as independence

Mr Keramane smiles. “Somewhere in Algiers, someone is probably being murdered right now,” he says quietly. “Somewhere in Algeria, they’re burning a town hall or a government building. But that doesn’t mean that the rest of us stop working.” And I could not help recalling – no offence meant to the Algerian ministries of foreign affairs, communications and interior – that in the last days of the Third Reich, even as the Soviet tanks were driving into Berlin, German civil servants in a shell-blasted building were working out the paper-clip ration for 1946. Is this supposed to be the solution to the Algerian tragedy, that the technocrats calculate the country’s debt servicing while the body politic collapses outside the front door? How long can you fiddle while Rome burns?

Keramane enjoys my puzzlement and consternation. He blames the “terrorists”, Islamic “gangs”, men who have – and this is what he said – “brought an alien, Afghan culture into Algeria”. It is the only moment when he shows emotion, this attack on the identity of the government’s enemies. But if this is about alien identity, I ask, what about Mr Keramane himself? He is speaking French rather than Arabic, is dressed in French clothes rather than an Algerian burnous gown; he received his degree from the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris. Who is he to talk about alien culture? “Actually,” he says quietly, “my clothes come from London.”

It is like living in two worlds. As I leave Keramane’s office, a bank official hands me a trade and investment profile which envisages three per cent growth, further foreign credit guarantees and a reduction in public debt.

Like the front page of El-Moudjahid and the friendly announcer on the television, it speaks of normality, a return to civilised life.

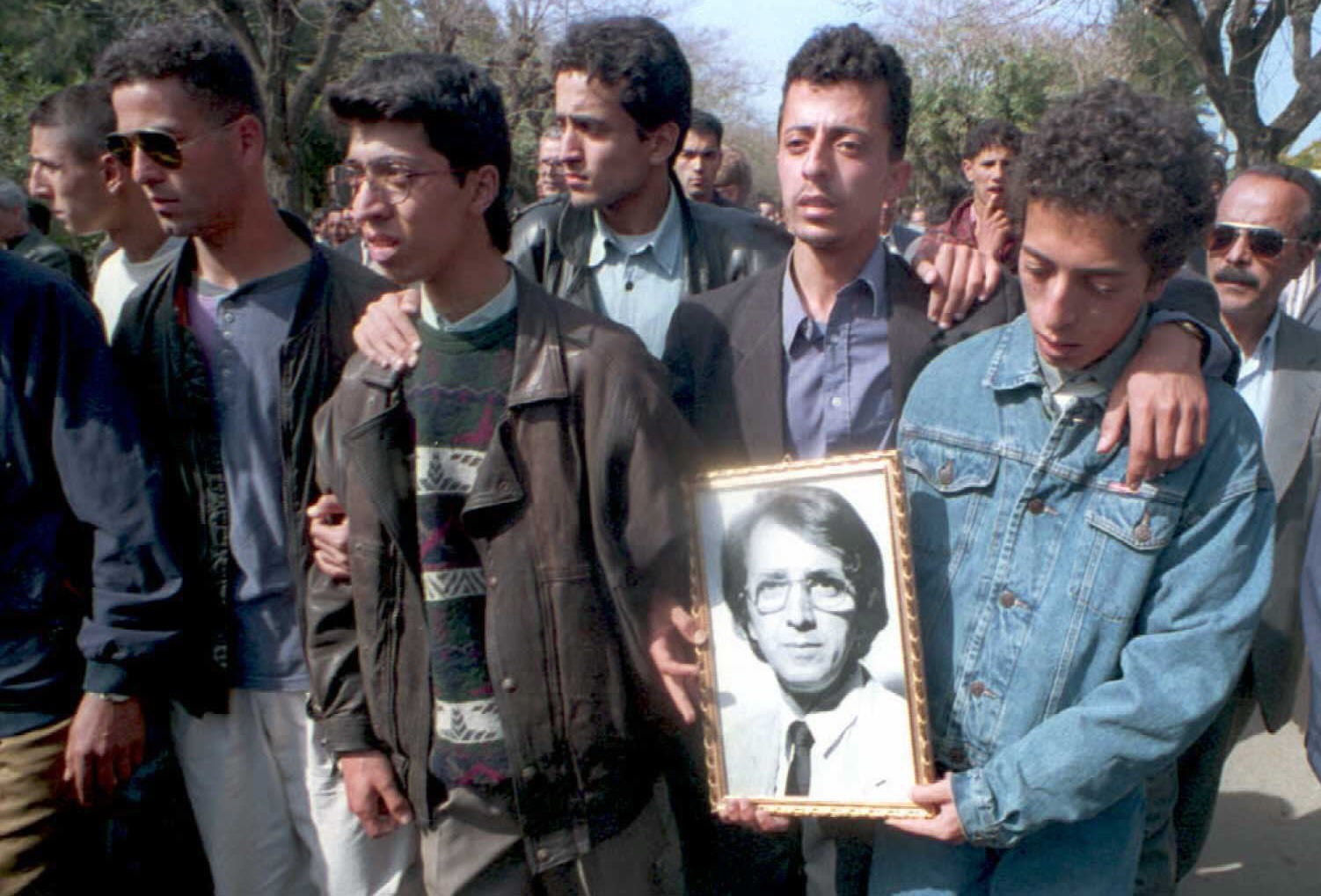

Soon I will realise it is all a fantasy. In just 14 days’ time, gunmen will shoot Rachida Hammadi, the friendly television announcer, critically wounding her and killing her sister, Houria, as the two women are walking to work not far from my hotel. A day later, it will be Ali Boukerbache’s turn to die, the film-maker who produced the murderous videotape that is lying on my bedside table, shot in his car as he drives to his company offices east of Algiers. And Mohamed Abderahmani, the editor of El-Moudjahid, the man who told us of the massive support for presidential elections, he too has only 21 days left to live. He will be trapped by gunmen in a traffic jam on his way to work, still without the police protection he pleaded for, unable to flee from his car as the men fire nine bullets into his body. A week later, Rachida Hammadi will die of her wounds in a Paris hospital.

Is Algeria’s veneer of civilisation, its Francophone, nationalist soul, being cut down by a new Khmer Rouge – or “Khmer Vert” as the Algerian press calls them – which regards art and learning and culture as enemies, to be torn out of the country as cruelly as throats are sliced open? That, at least, is what the government would like you to believe. That is what the gendarmerie tell you, the ski-masked policemen – the “ninjas”, as they like to be called – who prowl the worst streets of Algiers to represent the government’s fading authority. “Just a gang of terrorists,” one of them says to me after we have been ambushed by roadside bombs in the countryside near Blida. “A small criminal gang, a band of them, that’s all.”

I had been travelling with him when his patrol was attacked and had noticed how the cops, after the four huge bombs had blasted the roadway around us 200ft into the sky, had begun to pray, mouthing words from the Koran, that God is great, that Mohamed is the prophet of God, that God is all-merciful. It intrigued me, this praying, in a way I did not at first comprehend, lying by a ditch as the sky rained concrete and metal. It went on and on, for minutes, for an hour after the ambush, God is great, God is great, Thanks be to God. And it was only after we had found the wires that detonated the bombs and tramped through the fields to the railway embankment where the Islamists had detonated them, that I understood. The police had thanked God for his mercy but only seconds before the explosions, the bombers, lying here on this embankment, must have used the same words, must have quoted the very same words of the Koran, seeking God’s grace and invoking the prophet’s name in their endeavour to kill us all.

Even more remarkable were the historical parallels. Four decades ago, these same roads of the Mitidja plain were the scene of almost identical ambushes. Blida was a stronghold of the National Liberation Front, the FLN, the guerrilla army which eventually won independence for Algeria from France. Then it was the FLN which set off the bombs and the French who were ambushed. Now, in a postponed action-replay, the Algerian police are impersonating the role of the French, attacked as ferociously as their fathers once assaulted the colonial power. Somewhere in the recent past, it seemed, a culture had divided, a kind of historical fission which doomed the children of the revolution to re-enact the tragedy of their parents. And I remembered how, just a day earlier, the Algerian prime minister, Mokdad Sifi, had tried to explain the phenomenon of “terrorism” by asking me if I had ever heard the name of Mustapha Bouyali.

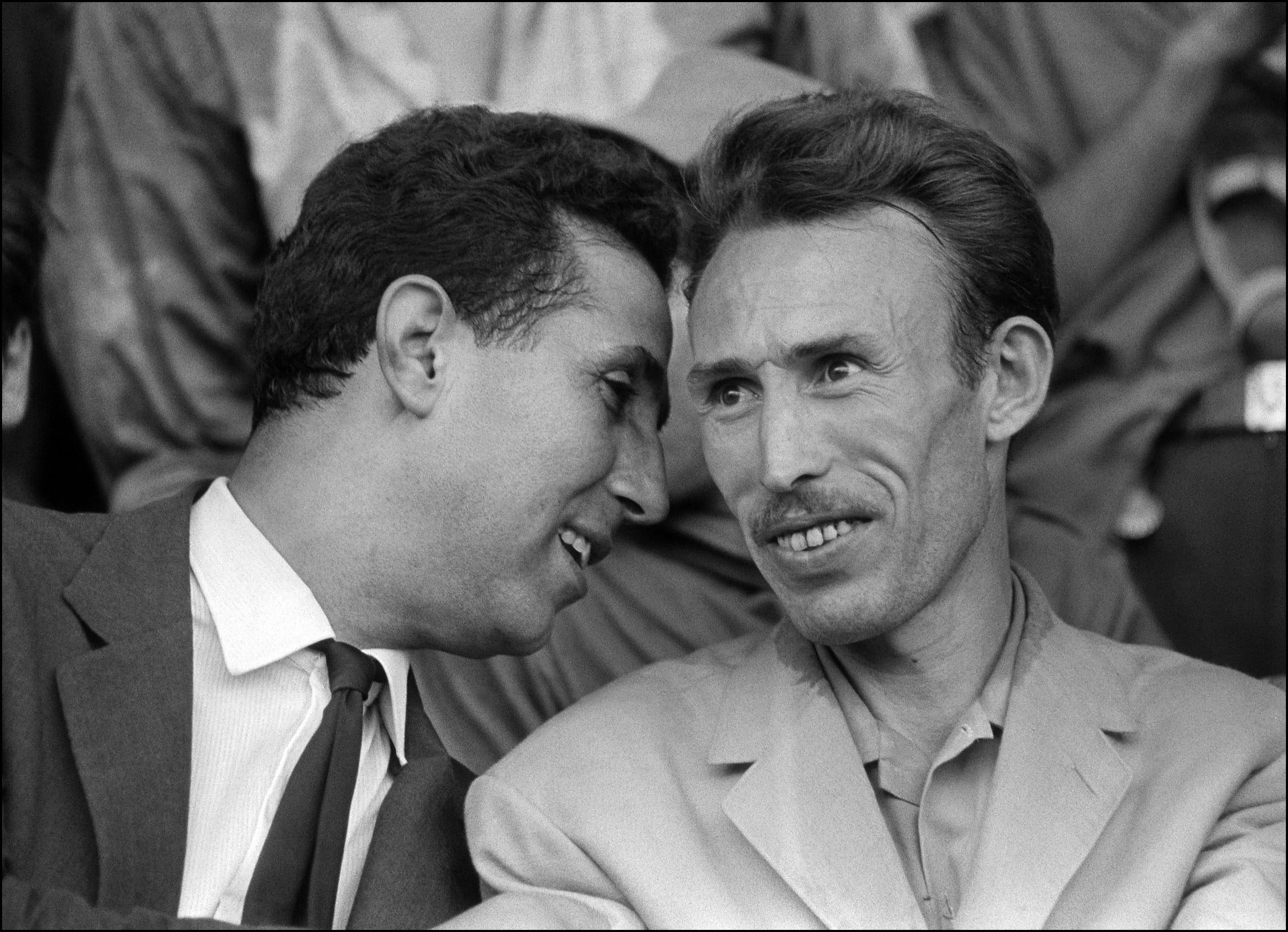

Of course I had. Bouyali was in the National Liberation Front, fighting the French; then he turned against his old FLN comrades and became the founder of what was to become the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) – which now threatens the very fabric of the Algerian regime. Indeed, Bouyali was a man whose family I knew personally, because, three years ago, in a less-dangerous Algeria, I had spent days investigating his life – a life which contained the seeds of Algeria’s tragedy. Born on 27 January 1940, when France had already ruled Algeria for 110 years, he was not quite 47 when he died, old enough to have fought against the French, young enough to have turned a war of liberation into an armed Islamic uprising, to have split the nucleus of Algerian history.

Bouyali’s village of Ashour, like thousands of small towns all over the country, looked French rather than Arab, its two-storey villas and tree-lined streets and Hotel de Ville redolent of the Cote d’Azur rather than the Maghreb. The great cities of Algeria – Algiers, Constantine, Oran – reminded visitors, as they still do, of Marseilles or Lyons. But elections had been so flagrantly rigged by the French that Muslim Algerians could never achieve equality; political reforms from Paris were introduced far too late to smother growing Muslim nationalist sentiment. In 1945, European settlers and French gendarmes and soldiers butchered around 6,000 Algerian Muslims in revenge for the Muslim murder of 103 Europeans in the town of Setif; Hitler’s Germany had collapsed and – like so many of the little bloodbaths in Algeria today – the massacre scarcely merited a paragraph in the European papers.

Bouyali’s private revolt was not difficult to understand. In 1962, Ben Bella had re-instituted torture. Within 12 months, free trade unions were abolished

When the FLN declared war on the French in 1954, Paris saw the puny guerrilla force of “terrorists” as nationalist in sentiment, drawing their inspiration from a larger Arab struggle against colonialism and their encouragement from the collapse of French power in Vietnam. These “isolated terrorist bands” – the present Algerian government employs the same expression for its Islamist enemies – would blow up power lines or railway tracks or murder isolated French pied noir settlers or gendarmes. Although the world was encouraged to regard the FLN as Nasser-ite in character, socialist in spirit, it is clear that an Islamist element existed within the guerrilla forces. Photographs in the Algerian museum of national resistance clearly show FLN fighters kneeling in prayer in the mountains of Lakhdaria and in the bled, the outback, in which the French army would ambush whole battalions of FLN fighters. Paragraph one of the FLN’s “national independence aims” of 1954 stated specifically that it wished to “restore” an Algerian state that was “sovereign, democratic and social, within the framework of the principles of Islam”.

Mustapha Bouyali joined the FLN two years after its declaration of war. He was 16 years old and collected funds for the FLN in Ashour. In 1958, the French arrested him and imprisoned him for two years but he escaped from their barracks at Blida and became an FLN officer in Algiers. There were other anonymous figures in the FLN at this time, colleagues of Bouyali, one of them – who tried to blow up a French government building – called Abassi Madani.

The eight-year war with France remains a defining moment in Algerian as well as French history, a cruel and brutal search for national identity as well as independence on the part of the Algerian fighters, a desperate battle for national pride and territorial integrity by France itself. Police torture, guerrilla bombings of civilians, massive military operations against the FLN which left no prisoners, the massacre of villagers by French paras, the individual murder of thousands of pied noir settlers and presumed collaborators and captured soldiers. Most of these were killed like animals, their throats cut, often their genitals pushed into their mouths.

In Paris last month, I bought a set of old French news magazines of the period, one of which was headlined “the horror of Algeria”. It showed a page of young men and women with their throats cut, the same expressions of monochrome terror on their severed heads as I had seen in the Algerian ministry of interior’s album of snapshots a few days earlier. The FLN, the men who formed the dictatorial, corrupt governments of post-independence Algeria, had used precisely the same methods to kill their victims as the Islamists do today. “In their actual techniques of liquidation,” Alistair Horne wrote in his magisterial A Savage War of Peace, “FLN operatives consciously endeavoured to achieve the gruesome... to belittle the dead man.” Horne listed throat-slitting, “le grand sourire, and other even nastier mutilations”.

General de Gaulle, brought back to power by the French army in 1960, promptly travelled to Algeria to assure the pieds noirs that “Je vous ai compris” – “I have understood you”– and then abandoned the settlers by negotiating personally with the FLN. A million French Europeans fled Algeria in 1962, abandoning generations of wealth and property and ancestral graves. The native Algerians who had remained faithful to France suffered a far more appalling fate. Up to 150,000 “Harkis”, Algerians who had served with the French forces, were murdered by the FLN. Horne records how Harki army veterans were made to dig their own tombs and swallow their French decorations before being shot or castrated or throat-slashed.

But independence brought no real peace to the Algerian victors. The surviving FLN leadership who had fought in the war were mostly deprived of power as Ahmed Ben Bella, who had largely sat out the war in Tunis and Tripoli, returned home to establish himself as president. Mustapha Bouyali, who joined the newly nationalised Algerian electronics company Sonalec immediately after the war, returned to arms within 12 months, in opposition to the dictatorship of Ben Bella, arguing that the “exterior”

FLN leadership had no right to decide Algeria’s future. He called a ceasefire when Ben Bella promised fair representation in the government. But in 1965, Houari Boumedienne, another of the FLN’s old “exterior” leadership, seized power in a coup d’etat, earning for the regime Bouyali’s further contempt.

Bouyali and other former FLN comrades-in-arms began to meet secretly outside Algiers to discuss the failure of socialism and the possibility that an Islamic state might provide a new future for Algeria. “You must see that what’s happening now in Algeria is the direct result of the opposition that Bouyali started in 1965,” Abdul-Hadi Sayah, one of his old FLN comrades, told me. “Our opposition wanted to work for a future, a democratic future, without bloodshed. Islam was a fundamental part of our belief – even when we fought the French. In our case our nationalist feelings were not as strong as our Islamic feelings.

“Our meetings were religious, yes. Our conversations in secret always started with readings from the Koran and we said ‘Allahu Akbar’, as we did when we entered battle with the French. The Islamic trend was very strong in us.”

Bouyali’s family still possess a photograph of Mustapha which shows him sitting cross-legged on the floor of a mountain cave, his hands uplifted in prayer, a Koran lying on the floor before him and a sub-machine gun standing against the wall to his right. It was taken just a few months before his violent death.

Bouyali’s private revolt was not difficult to understand. In 1962, Ben Bella had reinstituted torture. Within 12 months, free trade unions were abolished. Under Boumedienne, there were mass expropriations of land but there was nothing Islamic about such “socialist” measures. In 1967, supposedly to guard against “Zionist conspiracies” in the aftermath of the Six-Day Arab-Israeli war, Algerians were told it would be necessary for them to possess a government permit to travel abroad. Permits could only be obtained in return for huge bribes. Algeria was plunged into a state of semi-slavery. Boumedienne’s secret services tracked down Bouyali’s friends, one of whom was assassinated in exile.

Other men grouped themselves around Bouyali. One was Sheikh Naahnah, now leader of the moderate Islamic Hamas party. Another was Sheikh Ahmed Sahnoun. Mustapha Bouyali began lecturing in the Ashour mosque, assisted by a Sheikh who was later to become an imam in France and who was – last year – to be arrested by the French police for involvement with the banned Islamic Salvation Front (FIS). Bouyali’s brother Mohamed recalled that he talked about Islam as a system of government... about political education in Islam. He denounced corruption... the whole village would be closed on Fridays because so many people came to hear Mustapha.” Police observation of Mustapha Bouyali continued when Boumedienne died and the even more corrupt Chadli Bendjedid took over.

In 1982, Algerian military intelligence decided to arrest Bouyali, surrounding his Ashour home with armed officers on 28 April. Mohamed Bouyali showed me the back balcony from which his brother escaped. He walked me through the little family house with its synthetic velvet sofa and vinyl-covered table. The balcony leans over some peach trees and it was down the trunk of one of these trees that Bouyali, as the intelligence men waited at the front door, climbed to freedom. A historical balcony, when you think about it; if it had not been there, Bouyali would have been captured and never permitted to form the maquis which would, years later, become the armed Islamist opposition to the present Algerian government. A balcony and a peach tree changed Algerian history.

On the run, Bouyali held clandestine meetings with Islamic scholars. Some, like Abassi Madani and Ali Belhaj, would years later lead the Islamic Salvation Front to victory in parliamentary elections – elections which the military regime would cancel. Madani and Belhaj are now under house arrest, already visited, de Gaulle-like, by President Liamine Zeroual of Algeria in the vain hope of peace negotiations. Another colleague of Bouyali’s was Mansouri Meliani, who, nine years later, would help to form the Armed Islamic Group; he was arrested and imprisoned in 1992 but the GIA grew to the size of a full-scale guerrilla army. Both the FIS and the GIA, the twin hinges upon which the armed Algerian opposition now turns, are Bouyali’s legacy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks