Lawyers used cheap sheepskin parchment instead of vellum for centuries due to anti-fraud properties, research reveals

Cheaper and with handy fraud-detection built in, sheepskins helped prevent fraudsters pulling the wool over lawyers’ eyes, writes Harry Cockburn

While calfskin vellum was once considered the high-end writing material of choice for those in early publishing, new research suggests that medieval and early modern lawyers opted to use sheepskin parchment because it helped prevent fraud.

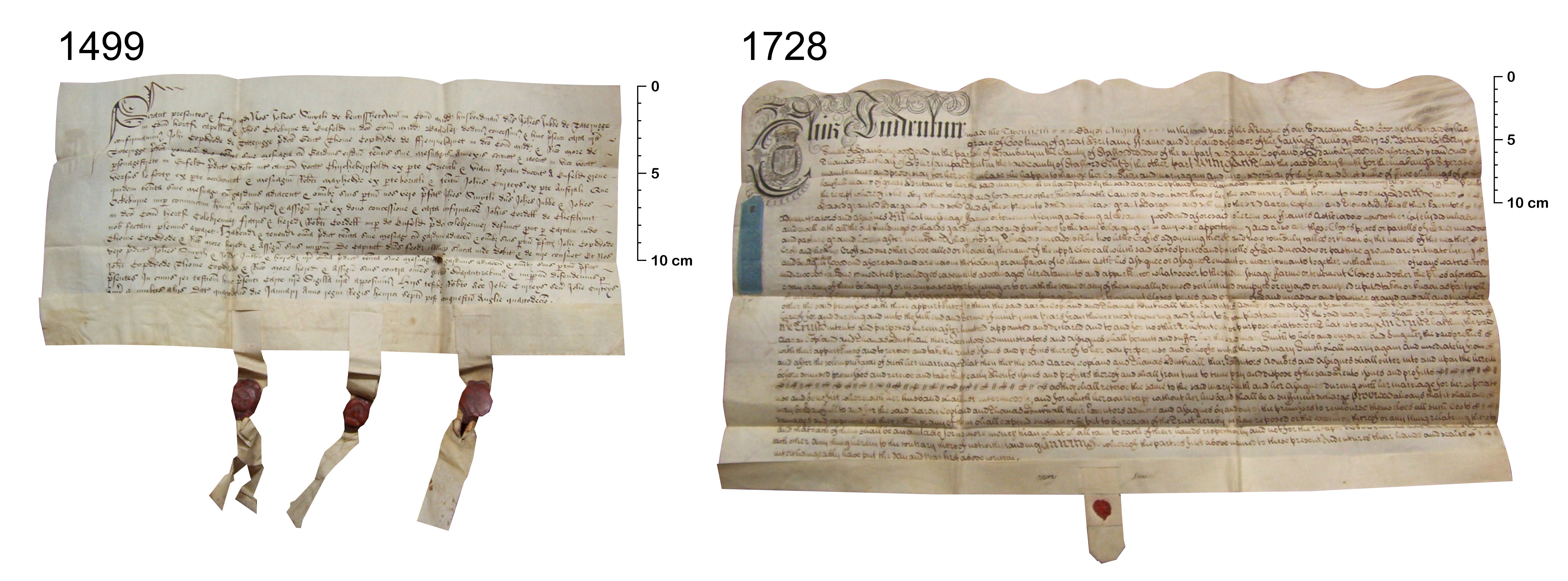

Experts from British universities identified the species of animals whose skins were used for legal documents dating from the 13th century all the way up to the 20th century, and discovered that, despite often having the means to use vellum or goatskin, they were almost always written on sheepskin.

The researchers said this could have been because the higher levels of fat deposited between the layers in sheepskins made attempts to remove or modify texts more obvious than with other animal-based stationery.

Sheepskin has a very high fat content, accounting for as much as 30 to 50 per cent, compared to 3 to 10 per cent in goatskin and just 2 to 3 per cent in cattle. Consequently, the potential for scraping to detach these layers is considerably greater in sheepskin than those of other animals. Such scraping would have been highly conspicuous and could have been an indication a document had been tampered with.

The use of sheepskin parchment as a writing material continued into later centuries probably due to its greater availability and lower cost, according to the academics from the Universities of Exeter, York and Cambridge, who carried out the research.

Read more:

Dr Sean Doherty, an archaeologist from the University of Exeter who led the study, said: “Lawyers were very concerned with authenticity and security, as we see through the use of seals. But it now appears as though this concern extended to the choice of animal skin they used too.”

Sheepskin is highly durable and long-lasting, and as a result, millions of old legal documents survive in British archives and private collections, but they have largely been neglected because of their supposed lack of historic value.

Many were discarded, burnt, or even repurposed into lamp shades during the 20th century – particularly after the Land Registry Act of 1925 meant a huge number no longer needed to be kept.

The researchers said that until their study revealed the high percentage of sheepskin, so little was known about these documents that many were incorrectly catalogued as calfskin vellum, when they were actually made of sheepskin parchment.

Dr Doherty said: “The text written on these documents is often considered to be of limited historic value as the majority is taken up by formulaic rubric. However, modern research techniques mean we can now not only read the text, but the biological and chemical information recorded in the skin. As physical objects, they are an extraordinarily molecular archive through which centuries of craft, trade and animal husbandry can be explored.”

Surviving texts hint at the use of sheepskin as an anti-fraud device. The 12th-century text Dialogus de Scaccario – written by Richard FitzNeal, Lord Treasurer during the reigns of Henry II and Richard I – instructs the use of sheepskin for royal accounts as “they do not easily yield to erasure without the blemish being apparent”.

In the 17th century when paper was common, Chief Justice Sir Edward Coke wrote of the necessity that legal documents were written on parchment “for the writing upon these is least liable to alterations or corruption”.

Professor Jonathan Finch from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York said: “What our research reveals is that there was a sophisticated understanding of the properties of different products and that these could be exploited. In the case of sheepskin parchment, its properties were used to prevent fraud by the surreptitious alteration of important legal documents.

“The structure of the skin clearly showed up any attempt to erase or alter the original text. The success of this study opens up new potential in the study of animal products over the historical period.”

The research is published in the journal Heritage Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks