A layman’s guide to understanding a fashion week runway show

Why is there a giant unicorn? Why aren’t the models smiling? Where are their pants?

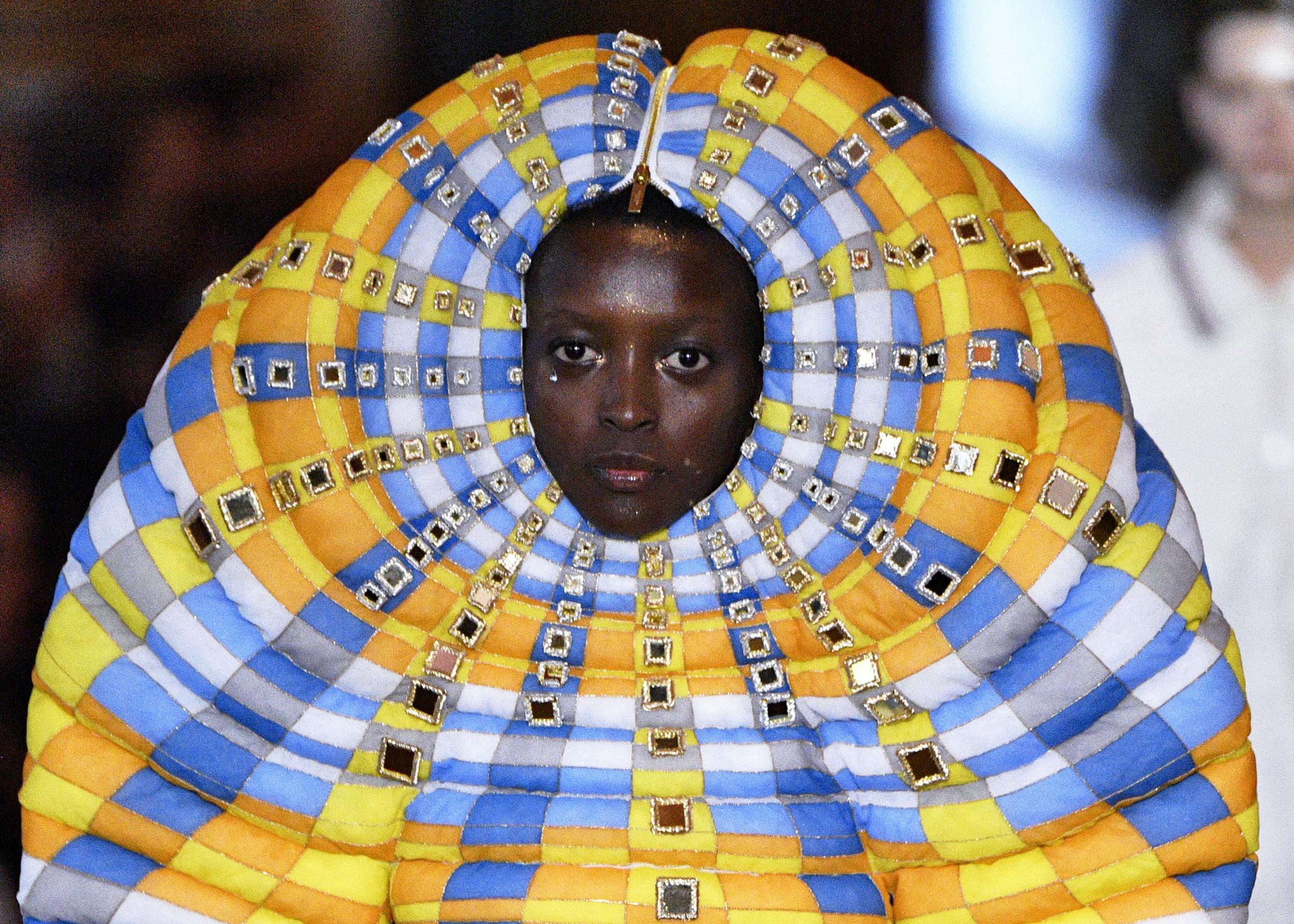

In one of the most dynamic runway shows last autumn, Thom Browne ended his Paris presentation with a model dressed in white guiding an enormous unicorn puppet. Two dancers, padded like marshmallows, had opened the show, flitting and twirling across the wooden floor of the majestic City Hall. In between, models crept precariously atop daunting heels in exquisite attire one could never wear to the neighbourhood market.

What is a casual consumer of fashion supposed to make of such a sight?

Browne does not like to explain his shows. Interpretation, he has said, is up to the beholder.

Not that long ago, the only people who would get to see such a fantastical presentation were fashion industry insiders and the journalists who cover that world. Now, however, some of the most theatrical and esoteric runway shows can be viewed by virtually anyone. Sponsors and charities enable those with a healthy bank account to buy their way into a show. Fashion houses live-stream their presentations, and journalists upload show videos almost before the designer has taken a bow – or you can see pretty much the entirety of a collection on Instagram.

When runway shows veer towards the more experimental, they can be as confounding as expressionist art or atonal music. What does it mean? What is the point? Doesn’t anyone offer the equivalent of “music appreciation” classes to help a newcomer make sense of fashion?

A few fundamentals can make the experience more rewarding – or, at least, less exasperating.

As the autumn 2018 runway shows begin in New York this week, some will be a straightforward parade of models in expensive but familiar-looking clothes, presenting a simple idea: “This is what I will offer for sale next season”.

Most designers need to project and to exaggerate so that their message reaches the cheap seats – or at least the most oversaturated viewers. Tom Ford sells glamour and sex appeal to a confident, sophisticated customer. But on the runway, he turns up the volume. Nipples are visible, blazers are worn over bras, models wear tops but no bottoms. He forces the observer to ask: is that acceptable? Is that decent?

Others have more complicated aspirations. Prabal Gurung says he wants to connect his runway show to the broader cultural conversation. Alexander Wang treats his presentations as parties – emphasising the street-cool, nightlife-loving attitude of his clothes. Tommy Hilfiger has used the runway as an enormous Instagram backdrop, organising a two-day carnival for his autumn 2016 collection. Marc Jacobs crafts a mysterious fairy tale – sometimes with provocative music, or more recently with a soundtrack of silence.

But whether the shows are straightforward or avant-garde, they leave many civilians with questions.

Why don’t the models smile? (Because they are in character, and have been given directions by the designer to appear strong, confident, tough, aloof, nonchalant, whatever.)

Why are they walking so fast? (Because speed exudes energy and urgency. And when there are 10 shows in a single day, dawdling is annoying.)

What’s with all the weird stuff? (Wouldn’t you get bored looking at little black dresses?)

Who would wear that? (Plenty of folks, maybe just not you.)

“A novice should simply sit and enjoy a fashion show – not over-intellectualise it or under-intellectualise it,” says Browne. “Everyone should have their own opinion to what they see in fashion shows. A good fashion show provokes some type of emotion, some type of feeling. A good fashion show, you should either love or hate.”

The mushy middle is forgettable. Dispassion is failure.

Designers have been staging runway shows in New York since the 1940s when a rudimentary version of fashion week was established by the publicist Eleanor Lambert (who died in 2003 aged 100). A new book from the Council of Fashion Designers of America, American Runway: 75 Years of Fashion and the Front Row, celebrates this tradition, noting the cultural shifts that have transformed the runway, and the simple mechanics of how a show works, from set construction to the models’ facial expressions.

It’s written by Booth Moore, who has covered the fashion industry for the Los Angeles Times and the Hollywood Reporter, reviewing countless runway shows over a decade. Still, her research left her surprised by both the amount of planning and the inevitable chaos that epitomise these productions.

“As slick as it looks online, there’s this High School Musical element to it,” Moore says.

Even the most mainstream shows – Tory Burch or Michael Kors, for example – will exaggerate the hair and make-up on the models to create a heightened reality. “And every photo is photoshopped,” Moore notes, if only to correct for colour or lighting.

For designers determined to tell a whimsical story or challenge the prevailing wisdom, an audience must suspend disbelief, as with a novel that indulges in magical realism.

“Why a unicorn on the runway in Paris – at this moment in history?” she asks rhetorically. “You’re not meant to take everything at face value.”

Browne, she notes, “takes a certain delight in making you feel uncomfortable”. And Marc Jacobs tries “to take you out of your comfort zone, make you scratch your head and say, ‘Whaaaat?’” That’s why those designers don’t offer show notes to explain their source of inspiration.

For many avant-garde designers, such as Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, the runway isn’t even about showing off clothes. It’s devoted to an intellectual exercise, “an exaggerated metaphor for what the collection is about”, says Valerie Steele, director of the Museum at Fashion Institute of Technology. A model dressed as a witch, for example, may be intended to explore “the transgressive aspects of women”, she says.

“The point of a more extreme show is to give you an idea, a feeling,” Steele says. “Clothes are not really a language, but more like music.”

Photographer Maria Valentino, whose company has shot runway shows for The Washington Post and other publications, warns baffled observers: “Don’t necessarily take it personally! A show is like an essay, a designer’s opinion written in fabric on the body, in a given time period.”

“It’s natural to see a fashion show and try to place it in the context of one’s own wardrobe or tastes,” she says. “But it’s amazing how delightful a show can be when you keep an open mind.”

Kors once noted that during his design process, he’d always ask his team: where is a woman going in that? The answer, he said, does not have to be the office, a restaurant or a soccer match. That woman could be Rihanna and she could be heading to centre stage. Fashion needs to be wearable, but it doesn’t have to be practical.

For anyone lucky enough to sit in the audience of a fashion show, the spectacle can be intoxicating. “There is really something special about being part of the live experience,” Moore says. “It’s the arriving, the build-up, the lights-down ... There’s a community aspect to it. It’s like if you’re at a Broadway play: it’s different from being at home watching on TV.”

Filmmaker Reiner Holzemer, who recently released an intimate documentary about Belgian designer Dries Van Noten, was something of a fashion show novice when he began work on the project. “In order to get a real impression of a runway show and the work of a designer,” Holzemer says, “look through your eyes and not through your mobile phone, trying to get a good shot for your Instagram.” Otherwise, you’ll miss the visceral pleasure of it.

Most people, however, will consume runway visuals as video or still photography. Liz Cabral, a New York-based stylist, recommends viewing a collection in a video, if possible. “Find the most immersive, 360-degree outlet or experience available,” Cabral says. “A lot of brilliant clothes fall flat when looking at them strictly from a front-only, two-dimensional view.”

She adds that “hearing the soundtrack, watching the clothes move and being entirely in that moment is the only way to be truly captivated by these awesome 15 minutes of showmanship. Otherwise, they’re just clothes versus moments in time.”

Runway images are part of a continuum, representing shifts in the culture, changes in the way we think about gender and beauty. A single runway image situates a viewer in a particular era; a series of them serve as a timeline.

Consider that in the 1980s models were like Amazons – tall and toned, with hourglass figures. The 1990s ushered in the era of waifs, brutally thin but refreshingly quirky, jolie laide. And by the turn of the century, the old obsession with symmetrical bone structure had given way to a desire to showcase racial diversity and gender ambiguity.

Hyperbole and shock on the runway evolve into subtle changes and shifts in your closet. Frayed edges and unfinished hems were once head-spinningly strange. No more. Big shoulder pads come and go, and each time they return they jar the eye – until, suddenly, they don’t.

Steele says it helps to view runway images with a sense of context and history. “Do the research to know who (the designers) are and what they do. Otherwise, in a way, it’s kind of meaningless.”

Not that you need a degree in fashion history to make sense of, say, Raf Simons. But it helps to know that he’s Belgian and has a long-standing fascination with visual arts and street culture – hence the Blade Runner-inspired menswear show last summer that sent models in big raincoats down a damp, dimly lit lane.

“Without the research, you’re not in a position to know what the show is about,” Steele says. “Is it telling a story? Is it the same old story?”

For many consumers, the story won’t matter. And that’s fine. That’s fine with designers, too. Put simply, designers want to move viewers, stir an emotion. They want to get consumers to look their way. And ultimately, buy their clothes.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks