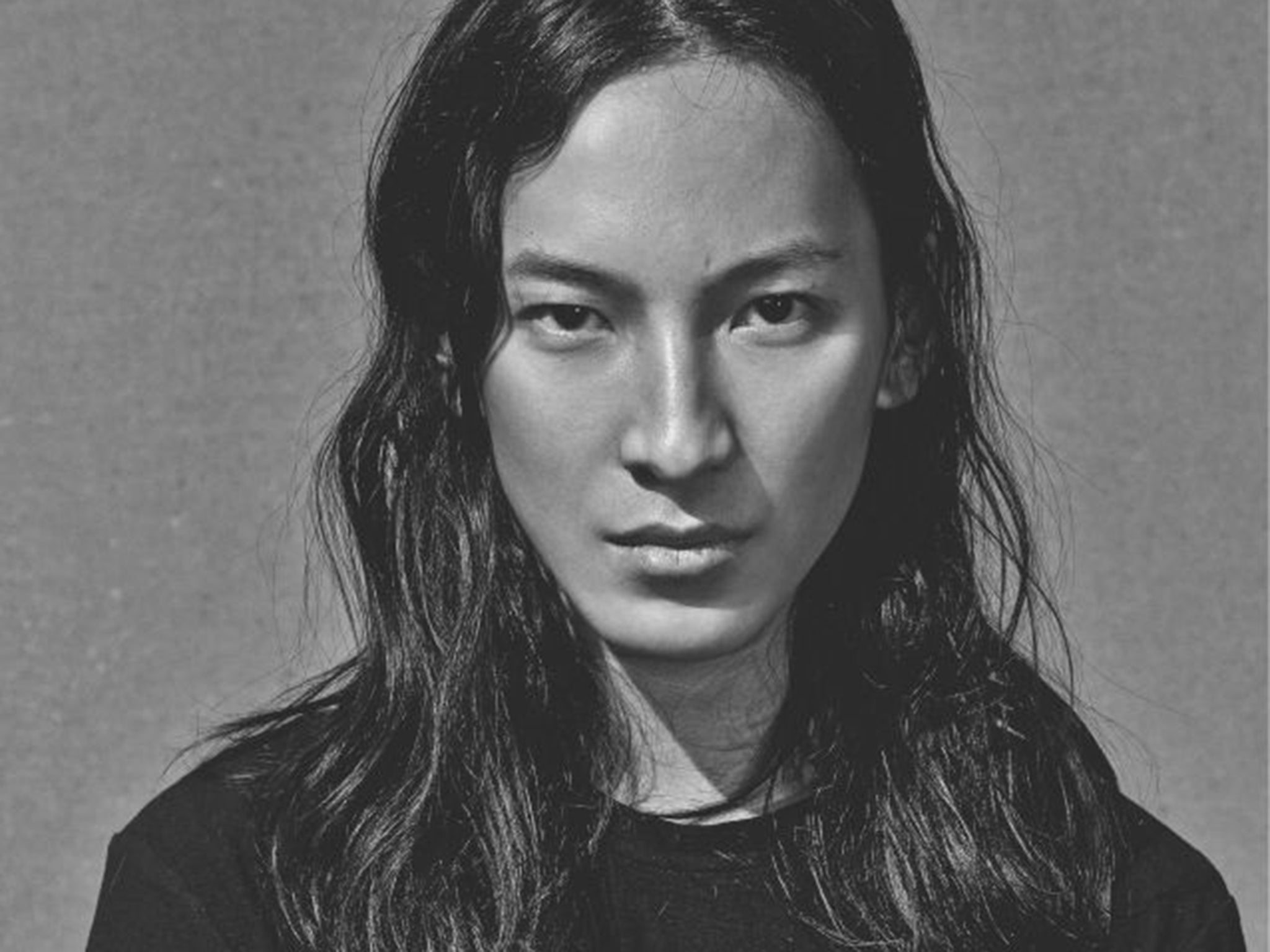

Alexander Wang bows out of Balenciaga after only three years

But then he was more a curator – as it is with many big fashion houses

Late on 2 October, the American designer Alexander Wang careened around a former church on the Left Bank of Paris. The site will soon be the headquarters of the Parisian house of Balenciaga. But Wang won’t be there to see it. After barely three years in his post, Wang is out.

Does it really matter, though? The important thing is not the designer, but the griffe – the label, in French. Balenciaga’s name has a permanence that outlasted its founder – and will do the same with the individual designers who devise the clothes in his wake. They’re a case neither isolated nor unique.

Fashion houses today no longer rise and fall with the strength of the talent installed in them. Or at least, that’s their odd new aspiration. They seek to exist in a separate bubble, protected by their own repute and the existing ubiquity of their names. Achieving immortality. Could you imagine Dior or Chanel ever escaping from the public consciousness, branded as those names are across many products well disconnected from the identity of their designers? Not really. Raf Simons once commented to me that he was attracted to Dior as a curator. “I don’t experience it as something that I have to make mine,” he commented. “It’s not mine.”

That is the point, with the vast majority of fashion designers and the labels that, these days, tend not to bear their names. These houses are not – and never will be – theirs. A number are eradicating extraneous associations with designers’ personalities from stuff like retail spaces: Balenciaga ironed out the idiosyncrasies of store design installed by its previous creative Nicolas Ghesquière, such as the artificial borders, blinking fluorescent tubes and rough-hewn walls. Plenty of people thought it was still unfinished when it first opened its doors. Today’s Balenciaga spaces are polished and slick, albeit somewhat anonymous.

Arguably like the clothes themselves. Wang presented his final collection on a clutch of models, and model-cum-actress friends. The clothes, though – slipper satin bias-cut dresses and slouched cargo trousers, spa-looking stuff when combined with the flat, floppy-floppy fabric sandals like hotel slippers – had nothing to mark them out, especially, as coming from Wang’s hand. They weren’t particularly Balenciaga either, although they bear the name, and will hence probably bear up sales-wise. A successor is yet to be announced, although rumours swirl.

Nevertheless, I’d argue that rumours swirl somewhat less ferociously than when Wang was appointed to Balenciaga in 2012, or when Raf Simons’s Dior appointment was announced the same year.

What has shifted in the interim? Perhaps we simply care less about what happens to Balenciaga. It was previously a cultish fashion fetish looked on, each season, to innovate and lead the way in ideas, if not in sales. Conversely, under Wang, Balenciaga’s turnover rose sharply, from £155m annually to almost £260m. At what cost, though? It feels as if the previously sacred walls of Balenciaga have been deconsecrated, like the church set to house it.

This malaise may be indicative of something wider than that. Fashion is built around a built-in obsolescence – the idea that clothes reach a sell-by date before they fall apart. Are the designers of those garments suffering the same fate? Appointing a fresh designer is an easy new story: magazines run profiles; people get interested. There’s a sense of something fresh and new afoot, while also the security of an established name you can trust, house codes you can rely on, an identity.

Rei Kawakubo’s clothes throb with her identity. She is, perhaps, the last great fashion maverick left. Or at least one of a rare and endangered breed. What Kawakubo labels as Comme des Garçons and presents in various inconvenient locations about the city on a biannual basis barely constitutes clothing, let alone fashion. They’re abstract concepts made manifest. If Miuccia Prada’s clothes are ideologically akin to the Rorschach blot, Kawakubo’s physically resemble them: amorphous, only vaguely anthropomorphic and open to endless interpretation.

“What do you think that was all about?” someone murmured to me, while I left the polished glass enclaves of the former Crédit Lyonnais headquarters. Kawakubo showed in its scummy basement, in a room I was reliably told was the smallest in the entire place. Her 2m-wide catwalk was frequently so filled with the blobby bumps of her clothes that two models couldn’t pass at the same time. Their lumps and clumps and feathery trims brushed the knees of the audience.

What did I think it was about? That sort of stuff. Touching. Sensuality. When Kawakubo not only shows blue velvet but plays a crooning soundtrack devoted to the stuff, you pay attention. There was something seductive above the sole package – and the models frequently resembled just that, trussed up in tactile layers of faux astrakhan, cockerel and ostrich feathers, their heads topped with coiffed crimson wigs, their mouths a geisha knot of lipstick.

Whatever it was about, it wasn’t anonymous. The important thing there is the designer. The label – even the label of “clothing” – is irrelevant. That’s what’s makes exciting fashion: ideas, not names.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks