Party politics: How Tom Kerridge’s £195 Beef Wellington became this Christmas’s most debated dish

This year Britain lost its mind over the pastry-wrapped fillet. From Tom Kerridge’s M&S showstopper to Charlie Bigham’s £30 ‘not-a-ready-meal’, Hannah Twiggs carves up the beef wellington debate and looks at what it reveals about class, chaos and desire for luxury without labour

It tells you everything about Britain in 2025 that the most contentious cultural artefact of the festive season isn’t a political budget, a tax rise or even a football result. It’s a beef wellington.

And not just any wellington, but the £195 Marks & Spencer x Tom Kerridge wellington – a truffle-laced, fillet-stuffed monument to extravagance that sold out immediately despite half the country calling it obscene and the other half insisting you could “make it at home for £40 if you weren’t lazy”.

Britain has, against all logic, entered a fully fledged wellington arms race. Which raises a question few expected to ask this year: how did a pastry-wrapped hunk of beef become the most political dish on the Christmas table?

To understand the wellington boom, you have to understand the psyche of a country that hasn’t had a good year since 2019. Since then – even if we ignore the global pandemic that has surely impacted much of the following – we’ve absorbed inflationary shocks, food shortages, supply chain collapses, shaky leadership, bird flu outbreaks, beef price surges and a cost-of-living crisis that no longer feels like a crisis so much as the new normal. National optimism has drained away. Disposable income has shrunk. The future feels smaller.

And yet, here we are, willing to spend anywhere between £30 and £200 on a single, high-stakes centrepiece for the Christmas table that can collapse into a soggy beige tragedy if you so much as breathe near it.

It’s illogical, indulgent and strangely defiant. It’s also very, very British.

The wellington’s extraordinary popularity makes sense when you consider the cultural anxieties it so neatly contains. It is both aristocratic and accessible, a dish that looks as if it belongs on a silver platter carried by footmen, yet is also recognisable as a distant cousin of the sausage roll. It signals wealth, but also practicality by promising to feed six to eight. It straddles aspiration and nostalgia, status and comfort, showmanship and familiarity.

Crucially, it is incredibly difficult to make well. It requires chilling, wrapping, precise timing, meat thermometers, a vigilant eye and nerves of steel. And yet supermarkets have performed a quiet miracle: they have turned this notoriously high-maintenance dish into a “finish-at-home” event requiring nothing more than faith and an oven preheated to 200C.

It is this duality – the promise of luxury without labour – that allows the wellington to slip so neatly into every corner of the class spectrum. The affluent treat it as a festive flourish; the aspirational treat it as a special occasion; the exhausted treat it as a shortcut to competence.

Every tier of British society can project something onto it. The wellington doesn’t smooth Britain’s class contradictions; it embodies them.

The romantic origin story (because there always is one) goes like this: the beef wellington was invented to honour the Duke of Wellington after his victory at Waterloo, a culinary tribute to British heroism and military might by way of a patriotic renaming of the French filet de bœuf en croûte. Because nothing says “British” more than nicking something from the French. It is a lovely story – the kind Britain specialises in – except for the awkward fact that there is no evidence it is true.

The Greeks were the first to wrap a flour and water paste around their meat to seal it before cooking, and the Cornish pasty has been around since the 14th century. Many of the earliest references to “beef wellington” actually come from the US as early as 1903, later appearing in a 1939 guide to where to dine in New York City and in a 1965 Julia Child’s cooking programme. It was also reportedly Richard Nixon’s favourite dish.

It might, in other words, be French by technique, American by popularisation and British only by force of personality, which may be the most accurate metaphor for modern British cuisine I’ve ever heard. And if the wellington is not, strictly speaking, Britain’s national Christmas dish, it is unquestionably Gordon Ramsay’s. If the dish had a modern patron saint, it would be him.

What makes this year’s Wellington Wars so potent isn’t simply the M&S price tag. It’s that Britain is suddenly drowning in beef wellingtons, each one doubling as a kind of edible personality test.

At the top of the food chain, Fortnum & Mason’s £120 wellington presides like an aristocrat at a village fete, designed for households where someone plays the piano after lunch unironically and “hamper season” is marked in the calendar.

At the opposite end of the social spectrum sits Charlie Bigham’s £30 working-class hero-turned-middle-class favourite, packed in its signature little wooden box – the one with staples so no one is allowed to utter the words “ready meal”, even though that is, of course, exactly what it is. That a dish once associated with the Napoleonic wars now lives next to Tuesday-night macaroni cheese is, arguably, the most British development of all.

Somewhere in the suburban middle sits COOK’s £90 “from frozen” wellington, the choice of families who own two cars, three calendars and one tired parent who refuses to compromise on standards. It is the sensible shoe of the wellington world: respectable, reliable and reassuringly devoid of ego.

Waitrose has gone full Noah’s Ark with two of every kind: mushroom wellingtons, salmon wellingtons, nut roast wellingtons and enough pastry-wrapped optimism to cater an entire Lib Dem fundraiser. These are not centrepieces so much as declarations of virtue with an expensive glaze.

Restaurants are conducting their own pastry arms race. At Kerridge’s Bar & Grill, the wellington arrives by the slice at £55; Hawksmoor has engineered a vegetarian version for the same price, proof that even carnivorous temples must occasionally bend the knee to 2025; and celebrated pastry chef Calum Franklin’s Pie Room at the Rosewood has turned the dish into a kind of architectural marvel for “Welly Wednesdays”.

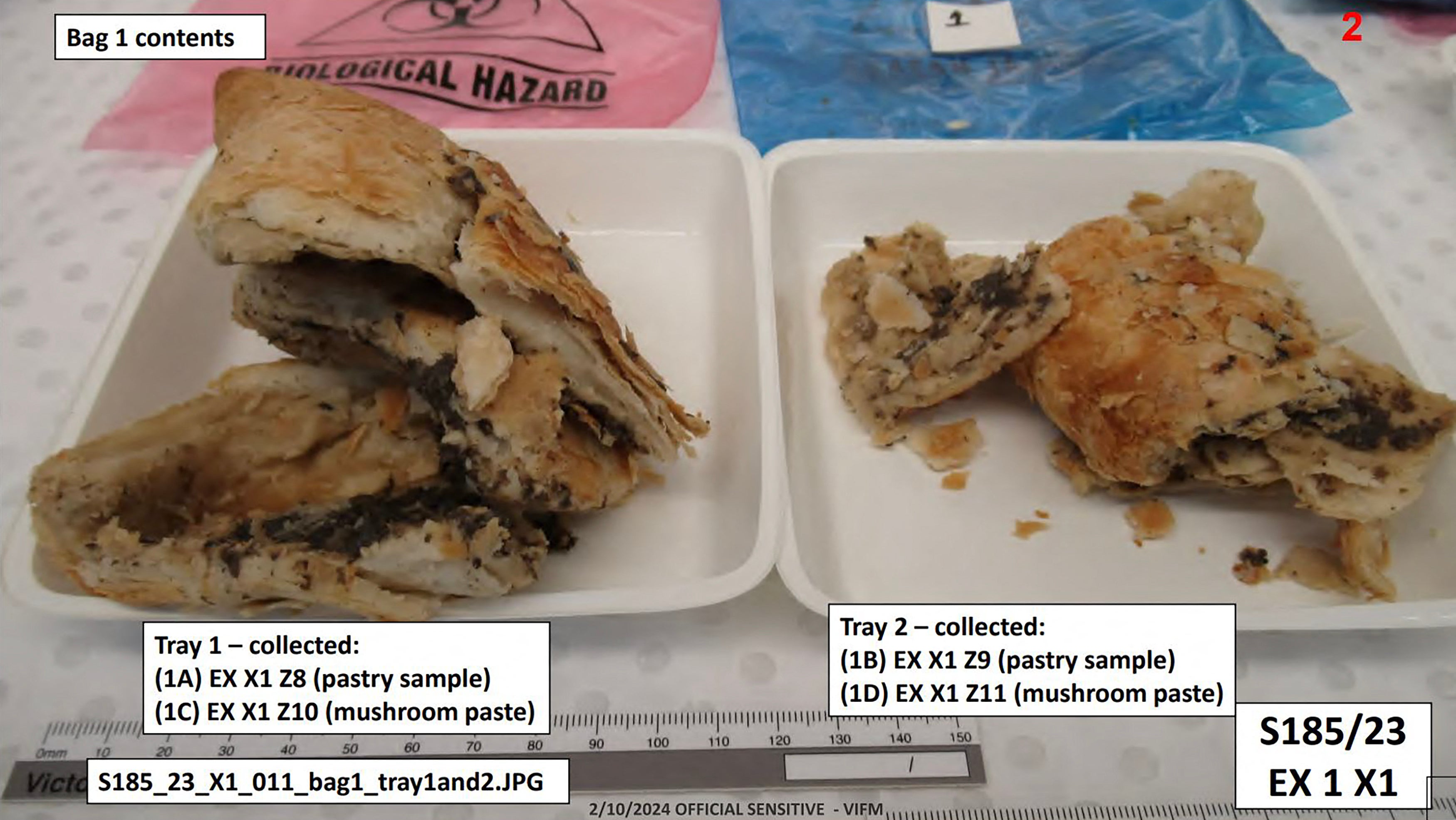

Oh, and there was also the poisonous, death cap mushroom-spiked killer wellington in Australia that briefly made everyone glance suspiciously at their duxelles.

All of which would be amusing enough, were it not happening against the backdrop of one of the most precarious Christmas food landscapes in recent memory.

This year’s market conditions have only intensified the craze. Bird flu outbreaks and constrained supply chains have made turkey unreliable and expensive, which in turn has pushed up the price of chicken – the protein Britons normally flee to when everything else goes wrong. Beef and veal prices have climbed sharply, mushrooms have suffered from rising energy costs in commercial growing, and even butter – essential for pastry – has had an inflationary wobble. By the time you’ve bought beef, mushrooms, decent pastry and a bottle of wine to steady your nerves, it can genuinely be cheaper – or at least less emotionally ruinous – to buy the whole thing engineered by someone else.

And yet, somehow, the very conditions that should have doomed the wellington have only made it more desirable.

Why? Because Christmas remains the last untouchable zone of national indulgence. If the rest of the year has felt compromised, Christmas dinner, simply, must not be. In a landscape of shortages and inflation, the wellington has become the culinary equivalent of dressing up for a Zoom call: an attempt to restore dignity in undignified times. If you’re the type of person who dresses the Christmas tree early, you’ve probably also got a beef wellington in your Ocado basket.

Perhaps the most telling contradiction is that the nation loudly derided the £195 wellington while quietly buying it anyway. If publicly the dish became a symbol of excess, privately, the numbers tell a different story. What people say on social media and what they serve on Christmas Day clearly are two entirely different things.

Ultimately, the battle of the beef wellingtons reveals more about Britain’s emotional landscape than its culinary one. It shows a country wrestling with class uncertainty, desperate for treat culture, nostalgic for glamour, weary of effort, suspicious of tradition yet clinging to it, eager to feel competent and festive in a year that offered very little of either.

It has become the national Christmas dish of 2025 not because it is historically British, but because it is symbolically British: aspirational, contradictory, theatrical, slightly absurd and held together by optimism and pastry.

In a country where everything feels uncertain, the wellington’s message is reassuringly simple: everything might be falling apart, but look! The middle is still pink.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks