How Britain scaled Peak Booze: 2004 marked the high-water mark in our relationship with alcohol

By 2004, the average Briton was drinking nearly three times as much as they had in the Fifties - and Chrissie Giles was above average. True, she lacked self-control. But, as she explains, our growing thirst has been manipulated by canny brands and a changing society

I first met alcohol in the late 1980s. It was the morning after one of my parents' parties. My sister and I, aged nine or 10, trawled the lounge for abandoned cans. I can still taste the stale, warm metallic tang of Heineken (lager; 5 per cent alcohol by volume) on my tongue.

Other times we'd sneak a sip of Dad's Rémy Martin VSOP (cognac; 40 per cent), even though we didn't like the taste. On special occasions we even got to drink legitimately: usually half a glass of Asti Spumanti (sparkling wine; around 7.5 per cent), served in the best glasses.

In my mid-teens I started to drink drink. It was easy enough to get our hands on booze, even though it's illegal in the UK to sell alcohol to anyone younger than 18. The bigger chain pubs checked IDs, so we stuck to the ones we knew to be less stringent.

Yet it wasn't until university that booze and I became properly acquainted. On Friday and Saturday nights, the air in Flat G4, Devonshire Hall, University of Leeds would be heavy with perfume and hair products. The five of us girls who lived there would sit on the floor of our kitchen, backs against cupboard doors, drinking from mismatched glasses and mugs. We were pre-loading: priming ourselves for the cheap spirits and pints that lay ahead with even cheaper vodka and red wine.

I found that drinking made being a human easier. It wasn't that alcohol made social anxiety disappear; that feeling would show up again the next morning. But drinking meant I could talk to people more easily, sometimes even dance. Still, there was always that one last drink that tipped me over the edge.

After I graduated, I found myself in a new city but with the same habits. I ended one night by grating my face along a north London pavement. The next morning I had a black eye and a need for a tetanus injection. Getting into a serious relationship didn't change things, either. I started seeing my now-husband in 2003 – a courtship unofficially sponsored by Stella Artois (lager; 4.8 per cent) and Smirnoff (vodka; 37.5 per cent). We were just doing what young people did. But recently, with getting on for 20 years of drinking under my belt, I started to wonder if my generation's relationship with alcohol was abnormal. I discovered that 2004 was Peak Booze: the year when Brits drank more than they had done for a century. Leading the way to this alcoholic apogee were those of us born around 1980. No other generation drank so much in their early twenties. Why us?

Everyone in alcohol research knows the graph. It plots the change in annual consumption of alcohol in the UK, calculated in litres of pure alcohol per person. (None of us drinks pure alcohol, thankfully; one litre of pure alcohol is equivalent to 35 pints of strong beer.) In 1950, Brits drank an average of 3.9 litres per person. The figure creeps up slowly in the Sixties, and more steadily in the Seventies. From the late 1990s consumption rises rapidly to reach Peak Booze in 2004, when we were drinking 9.5 litres of alcohol each – the equivalent of more than 100 bottles of wine.

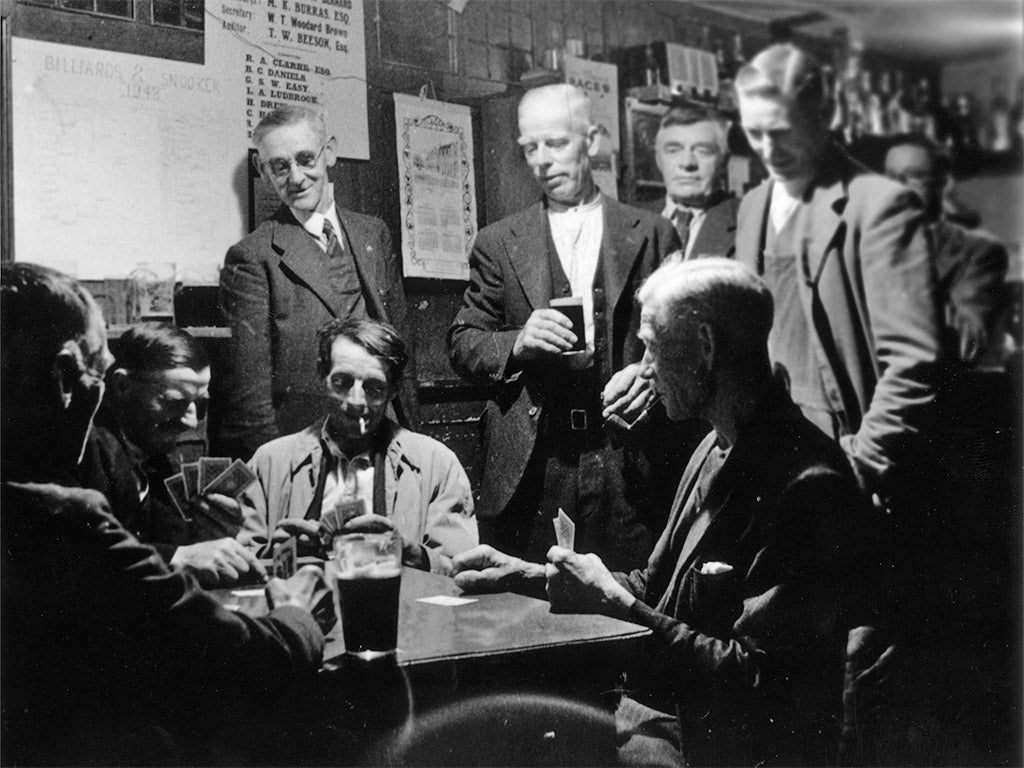

The story begins during the late 1930s, when a group of observers set out to record what went on in British pubs. The result was a book called The Pub and the People. The authors list the activities that took place in the pub: talking, thinking, smoking, spitting, playing games, betting, singing, playing the piano, the buying and selling of goods, including hot pies and bootlaces. And drinking, of course. In postwar Britain, much of the drinking took place in pubs. It was mainly men that drank there, and they generally drank beer. It wasn't until the 1960s that British drinking culture began to shift in fundamental ways, and the beginnings of the era of Peak Booze can be seen.

Part of this change was about Brits learning – or being persuaded – to enjoy a drink they had long shunned. Josef Groll made the first batch of Pilsner, the beer we now know as lager, in the Czech town of Pilsen in 1842. Word spread and, thanks to Europe's developing train network, so did the drink. Soon brewers from Germany started to make their own versions, and lager spread around the world.

But British drinkers stuck to their home-brewed ales. These drinks were weaker than the 5 per cent alcohol content of many lagers, and suited British drinking habits. "Mild [a type of beer] was about 3 per cent," says beer writer Pete Brown.

"Men who worked in factories and mines would drink pints and pints of it after work, partially to rehydrate without getting hammered." It also suited the UK tax system, under which beer is taxed in proportion to its strength.

But you can't keep the drinks industry down. The brewers promoted lager intensively after the Second World War. In the generation that came of age in the late 1960s – one thirsty for change – they finally found an audience. "Lager suddenly exploded, very quickly, after years of unsuccessful marketing," says Brown. What changed? "We were still doing most of our drinking in pubs, they were still male-dominated environments, the beers were still the same strength. But [Dutch brewer] Heineken in its advertising used 'refreshment' as a key benefit for the very first time in British beer advertising." When the ads first aired in 1974, the campaign was doing "OK", says Brown. But when Britain experienced unusually hot summers in 1975 and 1976, the refreshment angle gelled with consumers.

Suddenly lager started selling.

Between 1971 and 1985, annual sales of ale and stout fell by 10 million barrels, while sales of lager grew by nearly 12 million barrels. Lager now accounts for some three-quarters of total UK beer sales.

Around the same time that pub-goers were sipping their first pints of lager, many British drinkers were also developing a taste for another foreign import: wine. In 1960, wine accounted for less than a tenth of British alcohol consumption. But a few years later the government made it easier for British supermarkets to sell wine. The amount drunk nearly quadrupled by 1980, and then nearly doubled again between 1980 and 2000. In a survey published early this year, 60 per cent of 4,000 UK adults said they chose wine over other alcoholic drinks.

Wine is also important because it's mostly drunk at home. It's one reason why the pub is no longer the sole focus of British drinking. "The popularisation of wine represents one of the most significant developments in British drinking cultures over the last half-century – and it has been driven primarily by sales in off-licenses and supermarkets," writes James Nicholls, Director of Research and Policy Development at Alcohol Research UK.

The story of wine in Britain is also the story of women drinkers. Pubs were traditionally not particularly welcoming to women.

Today, the fact that a woman can walk into a pub in the UK and order whatever she wants is something we take for granted. It's largely the result of the profound change in women's financial and social status over the past half century. It's also a big part of why my generation drank so much. Alcohol consumption by women almost doubled in the three decades leading up to Peak Booze. Researchers who looked at the data a few years ago identified that change as one of the "key drivers" of the increased consumption seen in the UK.

The 1980s were an unusual time for the drinks industry. After 30 years of near-continuous increases, British drinking pretty much levelled out between 1980 and 1995 – the nation's thirst reined in, perhaps, by the high unemployment that gripped the country. But the alcohol industry had not pressed the pause button.

One of the industry's initiatives was the introduction of a new category of drink – a drink that had origins in a culture that originally posed a threat to alcohol companies.

Rave culture was part of my generation's adolescence, even if the closest we got was buying glow-in-the-dark bracelets and smiley-face T-shirts. I read the newspaper stories about illegal parties in warehouses and watched the news footage of people gurning on ecstasy.

There wouldn't have been many smileys in the boardrooms of the drinks companies, because ravers didn't want beer when they had ecstasy. That's probably part of the reason pub attendance fell 11 per cent between 1987 and 1992. The industry's solution wasn't long in coming, however. It began when the government used new legislation to force rave entrepreneurs into what Phil Hadfield, an alcohol policy consultant, calls a stark choice: "Work within the system… or be closed down." Some chose the latter option, but the more successful started licensed indoor dance venues.

The drinks industry wasn't going to miss an opportunity like that. It saw a chance "to reposition alcohol as a consumer product which could compete in the psychoactive night time drugs economies", according to alcohol researchers Fiona Measham and Kevin Brain. The industry launched new and stronger drinks, which it targeted at a young and culturally diverse crowd. First were strong bottled lagers, beers and ciders. Then came alcopops, including Hooch, in the mid-1990s. A few years later, drinks containing stimulants such as caffeine and guarana arrived. It was all part of the industry's desire to recast alcohol from a bloating depressant into a pleasant-tasting, stimulating drink that fitted the youth culture.

The industry was also hard at work transforming British pubs. One of the most dramatic stages in this evolution took place soon after alcopops were introduced, when pub chains such as the Firkin Brewery decided to convert old buildings – banks, theatres, even factories – into new drinking warehouses, often in city centres. This overhaul, argue Measham and Brain, was designed to attract "a new customer base… whose leisure sites were to be found in dance clubs, gyms, shopping centres". Not just old men, in other words.Shots were popular in these new pubs. Whisky chasers had accompanied beer in Scotland for years, but shots for shots' sake were new to the rest of the UK. Also new were members of bar staff coming to tables to sell the shots, which they sometimes dispensed from guns or holsters.

What the industry calls "vertical drinking" was the norm in these new venues. Smaller, higher tables replaced lower ones surrounded by seats, because drinkers are thought to consume more when they stand rather than sit. The loss of surfaces forced punters to hold onto drinks, which made them drink faster. Noisy surroundings made chatting harder, so people drank instead.

Marketing practices in pubs, bars and clubs, including happy hours and other drinks deals, encouraged us to drink more. In 2005, when changes in the law allowed pubs to stay open for longer, managers at some large vertical-drinking pubs were reportedly offered bonuses of up to £20,000 if they used sales techniques – upselling singles to doubles, for instance – to exceed revenue targets. All this was happening as the real cost of purchasing alcohol, allowing for inflation and changes in disposable income, fell every year from 1984 to 2007.

These changes, from the falling price of alcohol to the marketing of stronger, more easily consumed drinks, are thought to be behind the rise of what researchers call "determined drunkenness". Fortysomethings might get drunk on a night out, but it wouldn't be their explicit aim. It increasingly was for those in their twenties.

By 2004, Brits were drinking well over twice as much as they had been half a century earlier. The nation stood atop Peak Booze, and my generation was drinking the most. Most of us were too busy having a good time to notice.

But drinkers do all sorts of damage. Alcohol makes many of us unpleasant: verbally abusive, angry, destructive. Minor disagreements can become violent – part of the reason why around half of violent offenders are thought by their victims to be under the influence of alcohol. It's tempting to link the amount we drink with the frequency of alcohol-related harm, but it's hard to do so definitively because many factors are involved. Drink-driving casualties have been falling since the 1970s, for example, probably due to better education for offenders and media campaigns. British roads might also be safer because more of our drinking now takes place at home. Still, the steady decline in drink-driving fatalities of the last 40 years was temporarily reversed between 1999 and 2004 – a period that closely matches the rapid rise in alcohol consumption that led to Peak Booze.

The members of generation Peak Booze may well have harmed themselves, too. Our bodies don't help us much on this front: there are no pain fibres in the liver, so we can't feel the harm that we may be doing there. But the statistics roughly track consumption: annual alcohol-related liver deaths in England and Wales climbed steadily until around 2008, when the numbers levelled off.

Several experts told me that changes – since reversed – in alcohol policy that made booze less affordable were having a positive effect on liver deaths. The incidence of alcohol-related deaths, which includes nervous system degeneration and poisoning as well as liver disease, also began falling a few years after Peak Booze. Again, we don't know if these are linked or not.

Things seem to be different in the generation that followed mine. Young people are drinking less frequently, and more of them are teetotal. We don't know why: it could be financial hardship, an increase in the proportion that don't drink for religious reasons, or increased time spent online. Nor do we know whether the decline will continue. Still, this generation's relative reluctance to drink is part of the reason UK alcohol consumption in 2013 was only 7.7 litres per person, the lowest since 1996 and nearly 2 litres lower than Peak Booze.

For many of us in that generation, it's still normal to go to the bar after work on Friday. The weekend starting on Thursday is normal. Drinking because you're happy, because you're sad, because there's a random beer in the fridge – all normal. In fact, drinking isn't just normal to our generation. In some ways, it defines us.

I wouldn't say any of my close friends are alcoholic, but a fair few of us are more dependent than we'd like on that cold glass of white wine or cheeky gin and tonic at the end of the day. It's important to me to know that drinking is a choice, not a need. I want to be in control of what I do. Yet if I choose not to drink for one night out, I find myself rambling an explanation. The fact that staying sober for a month is seen as a feat of willpower, and the subject of charity campaigns such as Dry January, shows just how embedded alcohol is in our lives.

It's the grease that keeps many of our days moving. This would be fine if we chose to be part of the drinking culture. Sometimes it feels like it chose us.

This is an edited version of an article first published on mosaicscience.com. It is republished here under a Creative Commons licence

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks