The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Is pie and mash too ugly for the social media age?

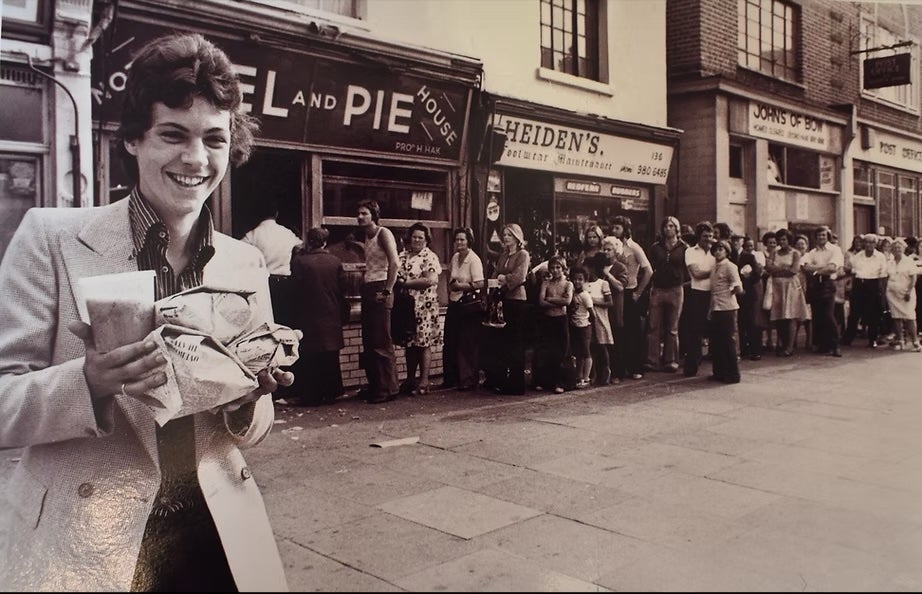

London’s most traditional dish has long resisted reinvention, yet its survival may depend on the very platforms accused of eroding culinary authenticity. Hannah Twiggs explores how an unapologetically beige institution is navigating visibility, nostalgia and a new generation of diners

There are foods that seem engineered for the internet. Burgers stacked to architectural excess. Desserts erupting with molten centres. Pasta that stretches, folds, glistens. These dishes do not simply feed – they perform.

Pie and mash, by comparison, appears almost wilfully indifferent to visual seduction. A pale dome of mashed potato (boiled, no butter or seasoning allowed), often unceremoniously slapped onto the plate, with connoisseurs still debating whether it should be “scraped” or “scooped”. A suet-bottomed, shortcrust-topped pie. A sluice of vivid green parsley liquor. Beige, beige and then – wham – council green.

It is not hard to see why the dish rarely features in the pantheon of algorithm-friendly meals. Nobody has ever accused pie and mash of being too glamorous. Which, depending on who you ask, may be entirely the point. It may also explain why recent headlines warn that barely 30 pie and mash shops now remain in London, a striking contraction for a dish that once sustained hundreds across the capital.

Few foods are as tightly bound to London’s identity as pie and mash. Like Cornish pasties in Cornwall, it is less a recipe that a cultural artefact – a dish that carries geography, class and memory in equal measure. And like many culinary traditions associated with the working poor, its reputation now oscillates between nostalgia and obituary.

Yet among those who spend the most time inside these tiled holdouts, the mood is notably less funereal.

“I’m half Greek and from West London. I didn’t grow up eating pie and mash,” says James Dimitri, an influencer who has made something of a personal project out of visiting every pie and mash shop in London. “The more shops I visited, the more it grew on me as a dish, to the point where I’ve even started craving it when I haven’t had it in a while.”

This is not the language of a dying cuisine. Nor is Dimitri persuaded by the more dramatic extinction narratives. “Most of the shops that were going to die out have already died out. Most of the ones that are left are packed. There are even some newer shops that have opened in the past few years.”

Part of the confusion lies in what pie and mash was ever meant to be. This was not celebratory food, nor aspirational dining. It was fuel. In Georgian and early Victorian London, long before restaurants became democratic spaces, pies were street food, sold by roaming “piemen” who wandered markets and dockside neighbourhoods hawking hot, portable meals to labourers with neither time nor money to spare. London’s fast food, if you like.

The dish itself evolved with London’s economy. Early pies were commonly filled with eels, once abundant in the Thames and imported in vast quantities from Dutch vessels. What we now recognise as pie and mashed arrived with Robert Cooke, who opened his first shop on Brick Lane in 1862 and helped codify the now-familiar combination of minced meat pies, mash and liquor. By the late 19th century, pie and mash shops had become fixtures of East and South London, many established by immigrant families whose surnames still echo across surviving shopfronts – Manze, Cooke, Kelly – dynasties that would come to define the trade.

If the plate itself resists visual seduction, the shops tell a different story. Traditional pie and mash interiors – tiled walls, marble tables, gilt lettering, counters worn smooth by decades of elbows – possess the kind of aesthetic coherence modern restaurants spend fortunes attempting to replicate. They are, accidentally, perfect vessels for the modern nostalgia economy.

They also come with their own set of quiet rules. Regulars will tell you pie and mash is eaten with a fork and spoon, never a knife. Salt, white pepper and chilli vinegar are not optional embellishments. The correct way to eat it is to flip it upside down, break open the bottom and dash the chilli vinegar inside. Even the accompaniments carry tradition: a carton of juice or, more canonically, a cup of tea. A side of stewed or jellied eels is suggested but not obligatory. For a dish frequently dismissed as visually unremarkable, pie and mash has an unexpectedly performative quality, which, in the social media age, may prove less a liability than an unlikely source of allure.

In Leytonstone, at Noted Eel & Pie House, a century-old family business, Alfie Hak, 28, represents something increasingly fragile in the pie and mash world: succession. He is the fourth generation of his family to work in the shop, though, like many heirs, he didn’t plan to. “College was more of a backup plan, in case it didn’t work out,” he says. “I’ve always wanted to be my own boss.” The shop, once a childhood obligation of weekends and school holidays, gradually became the most obvious route to independence.

Social media, he understood early, was not an optional extra but basic infrastructure. “Everyone says you’ve got to be on TikTok nowadays,” he explains. “So I started posting short clips.” Then the views began to climb. More importantly, customers began to appear. “People would come into the shop and say, ‘I saw you on TikTok, I wanted to come down’, or you’d get people saying, ‘I’ve never had this before but I saw you on TikTok’,” he says. “It’s working, basically.”

The numbers tell their own story. Hak’s account, That Pie Guy, now has more than 126,000 followers. Videos of pie assembly, shop lore and everyday counter theatre routinely attract vast audiences, with some reaching millions of views. “Thankfully, it’s always been a pretty busy shop. We’re quite close to West Ham and Leighton Orient, so you get a lot of football fans, and we’ve always had tourists coming in,” he says. “But social media has taken it to the next level. We’re getting all these different tourists in … people from Italy or France or America. We get a lot of Americans and Chinese.” They still get the regulars, too, but alongside them come what he calls, with gentle precision, “the new Londoners”: younger customers who seek out pie and mash rather than stumble upon it.

Social media did not rescue the business, so much as amplify it. More strikingly, he frames digital invisibility as a decisive factor in which pie shops disappear. “If you were to look at the last 10 or 15 pie shops that have closed in London, nine out of 10 of them would be ones with zero social media, zero online presence.”

Which points to a quieter generational problem. Many pie and mash shops remain family-run, but not all families produce willing successors. Older owners are often left operating in a marketplace they barely recognise. “They haven’t got a clue about social media or anything like that … Eventually, they end up closing down.” Had his own father been running the shop alone, the trajectory would have been different. “He might have retired by now … it would have just been a means to an end, because he wouldn’t have a clue about Just Eat, Deliveroo or Uber Eats.”

For Hak, social media’s role is therefore less cultural embellishment than commercial necessity. Yet the same platforms that deliver new customers can also distort expectations. Pie and mash, he reminds visitors, was never built for spectacle. “It was a food for the poor and the working class of London. It’s not supposed to be anything special … I don’t want people to expect to come in and have their minds blown by how flavoursome it is because it’s just comfort food.”

Its defenders would argue that this understatement is frequently misread. “It’s not supposed to be elevated,” says Dimitri. “Even when it’s bad, it’s not awful, and when it’s good, it’s not going to blow you away. Every cuisine around the world has dishes like this.

“A lot of people are put off by the liquor, but it’s just parsley, veg stock, butter and salt. Only two pie shops still use eel stock, as far as I know,” he adds. “Americans don’t understand that not everything has to be loaded with garlic and chilli powder,” adds Dimitri.

What emerges from these conversations is not a story of simple decline or improbable revival but something more recognisably London: a tradition negotiating relevance in a city that constantly rewrites itself.

Pie and mash has always been aesthetically unbothered. What threatens it is not ugliness, but obscurity. And thanks to the very platforms accused of eroding culinary authenticity, obscurity is, at least for some shops, no longer inevitable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks