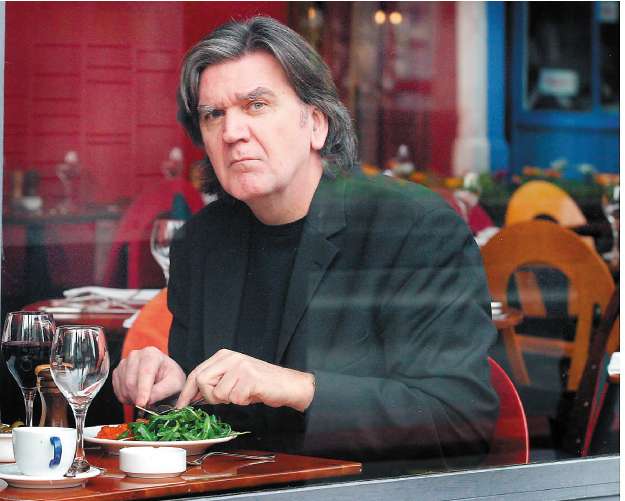

Terry Durack: Confessions of a food critic

A few flattering words, and the tables will be booked for months. Dish out the abuse, and all hell breaks loose. As a long-running battle over a scathing restaurant review is settled in the Court of Appeal, Terry Durack spills the beans on life as a food critic, while we ask his peers to reheat their worst kitchen nightmares

I've been accosted in the street, stalked by telephone, spat on, threatened with expensive litigation and labelled a fraud. I've been abused, schmoozed, patronised and poisoned – and all in the course of my professional duties.

I love to eat and I love to write, and I can't imagine a better job in the world than one that allows me to do both. I am a restaurant critic – and it's the job I was born to do. As a six-year-old, I had enormous cravings for smoked oysters, Polish sausage and dill pickles, but by 16, I was living in cheap lodging-houses and eating out of cans. Somewhere along the way my psyche confused hunger with flavour, love and security, and the die was cast.

I began my working life as an advertising copywriter in Melbourne, Australia, and moved to London in the 1970s, where I wrote Guinness, Special K and Rice Krispies ads for J Walter Thompson. This was back in the Mad Men glory days of expense accounts and long lunches, for which I found I had a natural talent. Returning to Australia, I started to write about my experiences in the Michelin-starred restaurants of Europe on the side, taking on a review column in the Melbourne Herald in 1988. Oh my God, that's 20 years ago.

So I have now been a regular restaurant reviewer for a generation, joining The Independent on Sunday when I returned to England in 2001.

Time to review the reviewer, then, and answer a few of the questions put to me by curious readers, irate chefs, and the 768,000 people out there who apparently want my job.

****

But what is my job? Telling people where to eat, and why. Occasionally, telling them where not to eat and why. I genuinely believe the world would be a better place if we thought more about what we ate and why. I see my role as helping people to find a good place to eat, helping also to build a healthy, inquisitive, demanding and sustainable food culture in Britain.

I want people to share my enthusiasm for good food and my horror in bad food. I have a few hidden agendas, too. I want to rid the world of inter-course sorbets, reheated bread rolls, horrible coffee, pre-grated parmesan cheese, and filled-to-the-brim wine-glasses.

My modus operandi is pretty simple. On average, I eat out seven or eight times a week, sometimes more. I write notes throughout the meal, and sketch the food.

Sometimes I take photos of it with a tiny digital camera, mainly because my drawings are so bad. In the early days, I used to hide a micro-cassette recorder under a napkin and talk into it, as if to my wife. That was silly, I do admit. It led only to hours and hours of transcribing, and is called "taking yourself far too seriously".

My reviewing style is somewhat different to the traditional British model. I'm Australian, and therefore classless, so I don't think it is at all vulgar to see food as something important in life. Therefore I tend to write about the food, and assume that my readers are sufficiently interested.

In each review, I try to be helpful by describing how the restaurant looks, feels and acts, giving examples of the menu, and putting the place in context, so the reader knows what to expect. Libel laws notwithstanding, I describe things as I see them. I try to have as "normal" an experience as possible, which means that I eat out with my wife or with friends.

I try to be fair by not reviewing on bank holidays or at times when the chef is likely to be off, by ordering food I think is representative, and by trying to find a wine that goes with the food (not easy given that my wife will only drink pinot noir). I look at things like location, space, noise, fellow diners, quality and appropriateness of cutlery, napery, lighting, the pacing of the meal, the value, and the perceived commitment by owners and staff.

The two questions I always ask myself are: "What is it they are trying to achieve here?" and: "How well are they doing it?" That helps me settle on a score out of 20.

Yes, I do get recognised. I am aware that the restaurant's public relations people send them photos of the major reviewers to post on the kitchen notice-board – that's just good business practice. But I have yet to find a restaurant that can go from being bad to good in the time it takes me to walk from the front door to my table. I don't resort to the tricks of some of my American colleagues, who have been known to don full disguises, wear floppy hats and refuse ever to be photographed in an effort to retain their anonymity.

I do, however, always book under an assumed name. I used always to use the same alias, until the restaurateurs twigged and spread the word. Now, I tend to use the names of the streets in my neighbourhood, although I do usually forget which street or lane I am masquerading as on any given night.

Often, I can tell when I have been spotted by the restaurateur because he/she comes to my table and starts telling me all about his/her business. I learn yet again that Monday was slow, and Tuesday was so-so, but Friday nights are very busy and Saturday nights make it all worthwhile. My wife gnaws her fingers off in boredom, and the score automatically slides down a point.

Smart restaurateurs note that I am there, and move on. They do not fall to their knees or cross themselves, they do not treat me as special, and they do not make my food any larger or more special than anyone else's. I once ordered a prawn starter that came as 12 perfect specimens arranged in concentric circles on a bed of perfect leaves. When I went to the loo, I checked out my neighbour's dish of five prawns thrown as if from a great height on to a smeared plate. Naturally, I reviewed that dish.

Likewise, good restaurateurs do not send out unsolicited dishes. They may do two of each and send out the best one, but I can't stop them being smart and opportunistic.

Nor do they offer the critic a free meal; I will always pay the bill in full, and I am insulted by the suggestion that I would accept a freebie.

Really, all they have to do is to make sure that the kitchen and floor staff are ready for any critic who might walk in, at any time. And the best way they can do that is to practise on their customers.

****

Don't get me wrong; restaurant reviewing is a wonderful job, but it's not all pork belly and pannacotta. I have been served fish that smelt like sewerage, and peas as hard as marbles. I've been given "home-made fruit salad" from a can and pure dairy cream from a pump pack. I've had crunchy pasta, demi-glace that tasted as if it were made of boiled-down horses, and bread so bad you couldn't serve it on an airline tray. I've had flies in my knickerbocker glory, hairs in my mash and cockroaches at my feet.

For every great dining experience, there are probably 100 that are rubbish, just waiting for me to come along. And while I don't actively look for restaurants to destroy, being tough is an integral part of being critical. If I wouldn't go back, how could I suggest anyone else does?

If you love good food, you are automatically drawn to those who grow, cook and serve it. Making friends with chefs and restaurateurs is tricky, because you cannot let the relationship affect your judgement. Almost inevitably, there will be tears before bedtime. In Australia, I was great mates with Neil Perry, chef and owner of the famous Rockpool restaurant. Yet the time came when I had no alternative but to drop his chef's-hat rating in the Sydney Morning Herald Good Food Guide from the long-held three to two. I hated doing it, but it had to be done.

Perry responded in the only way he knew how – by fixing the problems and winning the hat back the following year.

In Britain, restaurants suing critics is not a common occurrence, thank God. But in Australia, where I learnt my trade, the libel laws are tougher than old stewing steak. In three high-profile cases, Australian restaurant critics were successfully sued by restaurants, costing the Sydney Morning Herald fines in the vicinity of A$100,000 a pop. As a result, every review I wrote had to be scrutinised by the paper's lawyers.

So I wasn't able to write such things as: "To avoid the risk of food poisoning, I wrapped my entire grilled fish in tissues and hid it in my wife's handbag", although that is what actually happened. It goes a long way towards explaining why Australian restaurant reviews tend to be helpful, pleasant and, well, nice. The worst thing was that I realised I was censoring myself; aware that the lawyers were going to pick over each word like hungry vultures, I ended up avoiding saying what I really thought.

I still managed to be threatened with lawsuits on three different occasions (none ever came to court), and I have been spat upon by one infuriated chef's wife. At one point, I was phone-stalked by another disgruntled chef. He took exception to the fact that I wrote about a salmon dish he served on a plate so hot that the fish actually joined to the plate, and could not be prised off with a knife and fork. The chef began calling at all hours, leaving eerie singsong messages in his recognisable French accent about how he was going to get to me. The police tapped his phone for a while. Eventually he stopped calling.

Later, in Sydney, a small group of chefs who claimed I was too tough (miffed that I hadn't scored their restaurants higher) wrote an open letter to my editor in an attempt to get me fired. The editor simply published it; I didn't get fired and they didn't get any higher, or lower, scores from me than they deserved.

In Britain, it's different. A reviewer is free to describe food as "pretentious twaddle", "pit-dog ugly", "a cross between a dog's breakfast and baby sick" and "like chewing a trampoline" and not get sued – at least I haven't been... so far.

The most interesting responses have not been from lawyers, but from the restaurateurs themselves. After I had written an unflattering review of a new Carluccio's Caffe, I was approached by Priscilla Carluccio in the street. I braced myself for the worst, but instead, she made a point of thanking me, explaining how the team had acted on my comments, and that I should return to experience the difference. I was taken aback, not used to such intelligence and maturity in my restaurateurs.

The same cannot be said for my colleagues. My worst savaging came not from a restaurateur but from a fellow critic, upset at my favourable review of a Thai restaurant he had personally hated. He accused me, in print, of either being the chef's best mate, or his public relations man, and that I wrote the thing with "fists dipped in lard". I simply note that the restaurant subsequently received a Michelin star and that the reviewer is no longer a reviewer.

There is a culture here in which people read restaurant reviews in the same way that the Parisians used to sit close to the guillotine. They want the blood, the gore, the guts, the humiliation. A poor review can be a public assassination, a flogging, and for many readers, it is far more fun. It's a sad state of affairs.

So, is there a downside to a job like mine? Yes, a particularly weighty one. I am 6ft 3in, and got away with being rather large for a while. But one day, about four years ago, I stood on the scales and was horrified to see that I was 18st 4lb (116kg).

I made a few life changes, like cutting out seconds and thirds, not drinking during the day, eating porridge for breakfast, walking an hour a day, and eating more fish and vegetables and less pork belly and pannacotta. Within three years, I was down to 12st, and have pretty much stayed there since. I may love what I do, but there is no way I want to die on the job. This has in no way diminished my love affair with food and wine. I still eat what I want on a restaurant review, and drink like a fish. And as long as I feel I am contributing to the raising of standards and to the general enjoyment of all – especially myself – I'll keep doing it, thanks.

Terry Durack is restaurant critic of The Independent on Sunday. He is currently Glenfiddich Food & Drink Awards Restaurant Critic of the Year, and was named Best Restaurant Critic at Le Cordon Bleu World Food Media Awards 2007

Tracey Macleod, The independent

'Oh God, it isn't even cooked'

Coq d'Argent, London, 1998

My starter's terse description on the menu – "eggs in truffle jelly" – gave scant warning of the horror to come. I suppose I was imagining some delicate little quails' eggs nestling in a delicious bed of truffley richness.

What arrived was a big Pyrex bowl filled with a shimmering, cold jelly that looked, smelled and tasted like chicken stock straight out of the fridge. In its depths sat a single cold poached egg.

My companions crowded round it like concerned relatives round a hospital stretcher.

"Oh, God – it isn't even cooked!" breathed Helen, transfixed, as the egg broke open to release a stream of runny yolk into the jelly. No truffle flavour was discernible, though it may well have been lurking somewhere behind the all-powerful taste of animal fat.

It was impossible to manage more than a few mouthfuls.

Coq d'Argent was still taking bookings last night.

Matthew Norman, The Sunday Telegraph

'One hell of a restaurant'

Shepherd's, London, 2004

Where do you start with somewhere like Shepherd's? You don't. If you have any sense you finish with it... It would, in a more elegant age, merit a pamphlet rather than a review... Even the decorations are dreary, fake and pompous. It really is the eighth circle of hell, among the very worst restaurants in Christendom... Were the crab and brandy soup found today in a canister buried in the Iraqi desert, it would save Tony Blair's skin.

Shepherd's is still alive. This review caused its owner, Richard Shepherd, to threaten legal action against The Sunday Telegraph.

Jan Moir, The Daily Telegraph

'Nothing short of a disgrace'

The Ritz, London, 2002

Working in this nightmarish hotel de posh seems to have gone to the head of our hopeless sommelier. He keeps topping our wine glasses almost to the brim – even after being asked not to – and when a woman on the terrace nips off for five minutes, he fills her glass to the top and lets her expensive wine boil in the sunlight.

The Ritz is not just a disappointment, it is nothing short of a disgrace. It is haughty, out of touch and oozes disdain for its customers. It cost more than £250 to eat cold fish on a dirty terrace.

The Ritz survives. Following this review, the hotel's deputy chairman had a letter of complaint published in Moir's newspaper.

Michael Winner, The Sunday Times

'The glasses were filthy'

Cliveden, Berkshire, 1999

The service at Cliveden, if you can call it that, is unctuous, overbearing and utterly incompetent. At lunch we sat by the window. All you could see were the bottoms of day-trippers leaning on the balcony looking at the grounds. We ordered two Buck's Fizzes and I opened the wine list. This was beyond human belief. It said: "Half-bottles, page 31." But there was no page 31. Then I looked and realised page 28 is followed by page 31, then you have page 30 and then page 33. Page 32 is after page 33.

The Buck's Fizz arrived. Vanessa looked at the glasses.

"They're filthy," she said.

They were smeared with lipstick and washing-up grime. "Take them away. You wouldn't expect this in a transport caff," I said to John Rogers, the assistant dining-room manager. He left and came back with new glasses. No apology. Just a sneer.

"I think it came from the orange juice, sir," he said, referring to the dirt.

I've been dining in great hotels (which Cliveden certainly isn't) for well over 50 years. I can tell lipstick and smear-dirt from orange juice. If it was orange juice, why didn't Mr Rogers show it to us before taking the glasses away? It was just a typically inept response from a hotel parading as having class when it has none.

Cliveden remains open for business. Michael Winner has been formally banned from the premises.

Jay Rayner, The Observer

'The horror, the horror'

Divo, London, 2001

A little over a century ago my Jewish forebears fled that part of Eastern Europe then known as the Pale of Settlement. Having eaten at Divo, described as London's first luxury Ukrainian restaurant, I now know why. It was to escape the cooking. There are many words I could use to describe the food served here, but this is a family newspaper and none of them should be available before the watershed. I can't deny my disappointment because the remaining candidates – awful, calamitous, the horror, the horror – don't quite do it justice without the visceral attack of the expletive.

Top of the list is the Cossack Pork Sausage. The lengths of gnarled, under-seasoned gristly sausage arrived atop a lattice covering a ceramic bowl, which held a reservoir of burning liquor. Heaped on the sausage were crisp onion rings, which were immediately ignited by the flames from below.

"Now you blow it out," the waitress said, her anxiety rising with the plumes of smoke. "Now, please! Now!" This was the Red Army's scorched-earth policy realised in food.

Divo remains open. It no longer serves Ukrainian cuisine. A spokesman says it's now "more of a European restaurant".

Fay Maschler, The Evening Standard'

Just like debris in a drain'

Six Degrees, London, 2000

The waiting staff who congregated by the bar at the far side of the room... chatted merrily, looking around only very occasionally to see if they were needed.

Chicken laksa, an innately likeable dish and not difficult to assemble, arrived looking like debris caught in a drain and tasting not much more appealing than the image suggests. Crab and corn risotto with watercress and crab-claw buerre (sic) blanc was not technically a risotto and not a success on any other front, including spelling. Even Pacific Rim food has to have some rhyme or reason.

I won't bore you with the main courses, save to say I haven't seen liver cooked so grey since I was at boarding school.

Six Degrees closed in 2006.

Giles Coren, The Times

'Inedible, untouched dishes'

Sake No Hana, London, 2008

The worst thing I ate, for incompetence, clumsiness, vulgarity and plain downright dumb misunderstanding of Japanese cooking, was a braised Wagyu beef dish called "gyuniku miso ni", which I think must translate as "the best beef in the world raped, razed and pillaged by Cossacks". So lovely raw, or just barely seared, this fine beef had had all the complex veining of fat melted out of it and been cooked down to a state of powdery stringiness reminiscent of "curry day" at school. It was £55. We ate a mouthful each. I called the waiter. "Yes, nobody likes it," he said. "Everyone says it's cooked too long." Back it went, barely touched, to the kitchen, but appeared, sure enough, on the bill. By what ancient laws of hospitality does a restaurateur ignore the repeated complaints of his customers and charge for inedible, untouched dishes?

Sake No Hana is still going strong.

****

Biting back: What chefs say about the critics

Pascal Proyart

Head chef, One-O-One, London

I admire honesty: when someone criticises a restaurant it can be very upsetting, but some critics are very honest and very fair and I don't have any problem with that.

Some critics come in and already have an idea of what they want. They come up with a personal opinion rather than a general opinion. They're very opinionated about exactly what they want, and it's very hard to fight against that. Their ideas are already set, and that upsets chefs. They judge your food or you before they've eaten it, or based on a single visit. When it gets personal like that, I don't like it.

Sometimes they lack knowledge. Occasionally, you'll get a young guy coming in – even Michelin judges – and they give you an appraisal on the cooking that doesn't chime at all with what your guests say to you. So who's right? The critic or guests?

I've taken good points from people in the past. I think if someone has the public in mind when they criticise, it keeps a chef on their toes. It makes sure you keep to the standard you promised to deliver.

When a critic comes in, it's business as usual. If you tell the kitchen that Michelin or Terry Durack is coming in, you'll get them all panicked. At the end of the day, my most important critics are my customers. They are the ones who really judge you.

Chris Galvin

Co-owner, Galvin Bistrot de Luxe, chef-patron, Galvin at Windows, London

When you get a good review you're on a high and it's amazing for your business. It's a great buzz: the staff are happy, the staff's parents are all happy, the customers are happy.

We've had a kicking from time to time: that's the other extreme. It's painful and you take it personally. It's bad for the staff, for their parents. They wonder why their children are working here.

Food and drink is so subjective; sometimes you can have an off night and some critics find that the more controversial they are, the more readable they are. There are some who've made a living out of writing nonsense. But it's not worth getting into a fight with them: you'll always come off worse.

Sometimes a critic will give you a stinking review, but they'll be right. Fay Maschler has been brilliant to us over the years. But when I was at the Orrery she pointed out that a lot of the dishes had too much cream in them, and I thought "crikey" and then said to my brother, "We didn't think about that, did we?" And Jay Rayner gave us a bad review once, but he was right.

Criticism is painful, but you've got to swallow it. Restaurants aren't run by robots: we're all people and we're fallible.

Rowley Leigh

Head chef, Le Café Anglais, London

The critic's job isn't to represent other people's views. It's to represent their own – and they should do so in as entertaining a style as possible. The critic is there to express a zeitgeist, to describe the restaurant as a cultural statement, and their reviews are as much about that as about the specifics of wine and food.

Hardly anyone bases their reviews on more than one visit. That's the justice of the restaurant world: you're only as good as your last meal. I think it would give them a better perspective to come more than once, and taste a better sample of the dishes.

That would be my biggest complaint: critics always base their remarks on the first night. A restaurant is a complicated machine and it takes a long time to get one running really smoothly. A restaurant slowly acquires a life of its own, and I think critics should wait to judge a restaurant until it's been up and running for six months.

When a critic is in, you take care not to mess it up, or to make them wait too long. But to do anything extra would be dishonest. Chefs always do the best dishes they possibly can. I hardly ever know when a critic's coming. They've all done my new place now – so they'll leave me alone for another 10 years.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks