The best steak in the world: What is it about steak that makes people want to eat so much of it?

Beefy, bloody and bizarrely hard to get right, steak has an appeal far beyond the average piece of meat. Here, dedicated carnivore Mark Schatzker explains why he decided to travel the world in search of the primest cut

Of all the meats, only one merits its own class of structure. There is no such place as a lamb house or pork house, but even a small town may have a steakhouse. No one ever celebrated a big sale by saying, “How about chicken?” Stag parties do not feature two-inch slabs of haddock. Certain occasions call for steak – the bigger the better.

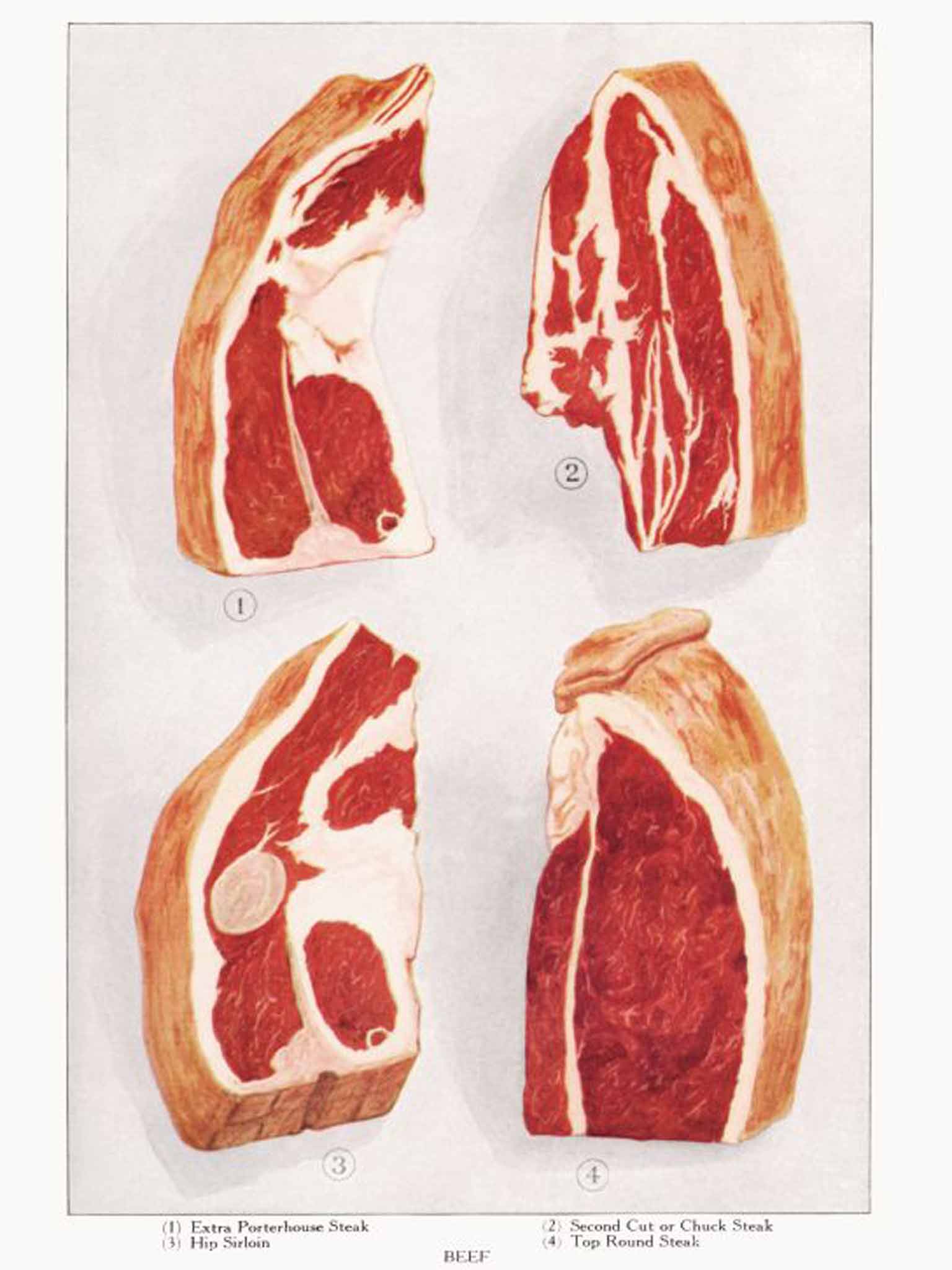

Steak is king. Steak is what other meat wishes it could be. When a person thinks of meat, the picture that forms in his or her mind is a steak. It can be cooked, crosshatched from the grill and lying in its own juice in a pose suggestive of unmatched succulence, or it can be raw, blood-coloured and framed by white fat, the steak that sleeping bulldogs in vintage cartoons dream of.

Steak earns its esteem the old-fashioned way. People don't eat it because it's healthy, cheap or exotic; it isn't considered any of these things. People love steak because of the way it makes them feel when they put it in their mouths. When crushed between an upper and a lower molar, steak delivers flavour, tenderness and juiciness in a combination equalled by no other meat. The note struck is deep and resonant. Steak is powerful. Steak is reassuring. Steak is satisfying in a way that only the pleasures of the flesh can be.

The best steak my father ever ate was one of his first. The year was 1952, and the steak was served at an establishment in Huntsville, Ontario, called MacDonald's Restaurant (not to be confused with McDonald's, the world's largest fast food chain). At $3.95, it was a high-priced item, considering that my father would earn all of $35 that summer as an assistant director of a boys' camp. An immigrant kid bent on medical school, he found himself with money in his pocket for the first time in his life. On his first day off, he hitchhiked into town and bought himself a steak. It arrived sitting next to a pile of fried mushrooms, and it was huge: a sirloin, an inch thick and a foot wide, its edges drooping over the side of the plate. Nearly half a century after eating it, my father is still moved by memories of the experience. He calls it “the fulfilment of my gustatory dreams”.

The best steak my cousin Michel Gelobter ever ate was in the Sierra Nevada during the summer of 1980. He was working at a pack station high up in the mountains, living in a small shack with two other guides. Further down the slopes, horses and cattle were grazing the summer pastures. He saw the cow alive before it became his meal. It was an unusually tall black-and-white castrated male – a steer – standing in a corral, where it was getting fat on hay, sweet sagebrush and grass. A few weeks later, his boss delivered meat up to the cabin, and the men started with the tenderloin, which is known in fancy talk as the filet mignon. They put it in a pan with salt and pepper, then placed the pan inside a propane stove. Michel doesn't remember cutting the steak or chewing it, but he does remember the flavour.

“It tasted buttery,” he says. “It was just slightly tougher than pâté and unbelievably juicy.” The steak brought all three men to the same level of extreme astonishment. “I don't think any of us had ever had anything like it,” Michel recalls. “It felt like a freak of nature. It was the best steak we'd ever had.” When the steak was finished, Michel went over to inspect the remaining raw beef. It was a dark brownish red, with lots of streaks of white in it. Since then, my cousin has been searching. He has eaten “a fair amount of steak”, some of it very good, but none equal to the Sierra Nevada steak of 1980.

The best steak I ever ate gave way between my teeth like wet tissue paper under a heavy knife. There was a pop of bloody, beefy steak juice, and I had to close my lips to keep any of it from escaping. The problem is, this steak lives only in my imagination. I haven't actually tasted it – not yet, anyway. It's a false memory, of the culinary variety.

There have been, certainly, remarkable steaks in my past, most notably one at a Peruvian chain restaurant in a suburban mall in Santiago, Chile. It was served on its own plate, separate from the French fries, allowing the juice to pool in a manner that seemed premeditated. It was not the most tender steak I have ever eaten, but its deliciousness floored me. When I was done eating it, I raised the plate to my mouth, tipped it up, and gulped the juice in one long, excellent sip. I was ready to order another one, but I had a plane to catch.

Steak came to me the same way consciousness did. One day I woke up, and it was there. My father started grilling it when I was around nine, as I recall, which is to say that's when he started sharing steak with his youngest son, because he had been buying and cooking it regularly ever since the trip to MacDonald's Restaurant. By the age of 11, I knew the difference between a New York Strip and a T-bone (the bone). When my parents visited their three boys at summer camp, they would bring cold steak, black cherries and icy cans of Coca-Cola.

My relationship with steak started getting, as they say, complicated in the early 1990s. My eldest brother Erik moved to South America, and began sending regular despatches on all the great steak he was eating. Every time I spoke to him on the phone, he evangelised about his latest filet or rib-eye, and I would hang up, jealous and hungry. One day he told me the secret to a great steak: season it only with salt and pepper. I went out and bought the most expensive steaks I could find and did as he said. The piece of meat on my plate tasted like textured salt water.

I did not give up. Most of the steaks I cooked resulted in textured salt water, but occasionally there was a standout. I bought a strip loin (a sirloin in the UK) at an above-average grocery store one day and pan-fried it according to a Julia Child recipe; it tasted so good I felt like taking to the streets and raving about its deliciousness through a megaphone. The next day, I returned to the same store and bought an identical-looking strip loin. It was terrible.

I began chasing steak in earnest the year I got married. My wife and I went to Tuscany for our honeymoon, and on our second night there we ate at a restaurant in Florence called Del Fagioli, a cosy little spot with chequered tablecloths and big flagons of Chianti. The waiter did not recommend pasta, veal marsala, or anything else that I had, until actually visiting Italy, thought of as Italian food. His advice: “Get the steak.” We did, and when I swallowed the first bite, I let out a string of four-letter words and fell silent for a duration lasting more than a minute. Then I swore some more. The steak was that good.

A few years later, I found myself on what may turn out to be the greatest journalistic assignment of the century. To celebrate its 20th anniversary, a glossy travel magazine called Condé Nast Traveler asked me to travel around the world in 80 days, the sole condition being that I wasn't allowed to fly. I saw it as a well-funded steak excursion, and the first night I found myself driving through Chicago, a city famous for its excellent and huge steaks. I went to one of the pricier steakhouses, one that claims to keep its own perfect bull down in Kentucky who has the enviable job of siring every one of the cows that provide the restaurant's steaks. The rib-eye it served looked perfect: black on the outside and red in the middle. It tasted like grilled tap water. A few days after that, still heading west, I drove over the Sierra Nevada – not too far from my cousin's pack camp – and dropped thrillingly down into California. That night I ate in Napa Valley, and the steak was so good I decided to have a look at the local property prices (which ended up spoiling an otherwise perfect evening).

A cruise across the Pacific Ocean and a train ride north through China brought me to Mongolia, where I ate the worst steak of my life. It was a T-bone, half an inch thick, grilled over a gas flame and so tough that in mid-chew I had to pause to let my jaw muscles rest. But it was only slightly more disappointing than a steak I once ate in Las Vegas, at an old and hallowed steakhouse recommended by a hotel concierge who assured me it was better than all the others. The strip loin I ordered turned out to be more than an inch thick, and looked too big to ever fit inside my body. It was expertly crisscrossed with gridiron marks, and as I cut into it, red liquid poured onto my plate. The level of expectation approached the dramatic, but that's where the story ended: at expectation. The meat had a watery texture and hardly any beef taste. It was one of the most expensive steaks I had ever ordered, and also among the most insipid. I took bite after bite, incredulous that something that looked so beefy could taste so limp. Eventually, I gave up. The waiter removed my plate and said: “It's a big serving.” I nodded sheepishly and paid the bill.

Steak was now a problem. It had become a culinary version of the weather in England: occasionally beautiful, but on the whole depressing.

Unlike the weather, however, steak was something no one paid any attention to. During steakhouse dinners, people would spend a minute, tops, deciding on which cut to order before turning to the wine list, which they studied like it was scripture. The meal would inevitably degenerate into an ad hoc seminar on grape varieties. Should we go with a California cabernet? No, a big zinfandel for sure. But not too oaky – I hate oaky. The steak itself enjoyed the same status as the napkins or the water: people just accepted what was given to them.

Why was it that, in steak houses all over North America, people were talking about grape varieties and not cattle breeds? Why was there an entire aisle at my local newsagent's devoted to wine magazines, but not so much as a newsletter about steak? Everyone loved steak, yet no one seemed to know a thing about it. What was going on?

What is it about steak, for that matter, that makes people want to eat so much of it? Why did my father continue to grill it on a near-weekly basis, even though no steak ever measured up to the one he ate in 1963? I suffered from the same disease. Like some pale-faced slot-machine addict, I kept exchanging money for steak, hoping to strike gold, but steak after steak said: “Better luck next time.”

Why was the meat all so bland? And what could account for those rare standout steaks? What made the Sierra Nevada steak my cousin ate in 1980 so different from those he's eaten since? I couldn't find any answer – not at my local butcher, not in the pages of cookbooks and not, incidentally, among wine connoisseurs, all of whom are undiscerning steak eaters.

The world, it seemed, reserved its gustatory passion for things like single-cru soft-filtered olive oil, 100-year-old balsamic vinegar, rare and exquisite Japanese sake, single-malt whisky, fine port and so forth. I knew of Italians who got into raised-voice arguments over buffalo-milk versus cows-milk mozzarella, Spaniards who feed acorns to pigs to make the ham more delicious and Americans who take barbecuing so seriously it has become a competitive sport.

So what was going on with steak? Had modern agriculture bled the flavour out in the name of efficiency and profit margins? Was steak just one more thing that wasn't as good as it used to be? Or was the reverse true? Had steak been improved and perfected to the point that we were all eating the red-meat equivalent of single-cru soft-filtered olive oil, and I was just some deviant outlier, someone who preferred Italian or Chilean steak the way others prefer French cars or Japanese vacuum cleaners?

The latter seemed more likely, given that at any moment I could step out of my front door and, within minutes, find myself consuming beer from Germany, mushrooms from Croatia, fish sauce from Thailand, cigars from Cuba or rum from Guatemala. If there was great steak out there, surely the forces of globalism would have found a way to put it on my plate. Like every other fine and expensive thing on the planet, it was just a matter of coming up with enough money.

But as I discovered in Mongolia, globalism missed the boat on mutton. This is the meat from a mature sheep, which the Western world gave up on long ago. (The only place it's ever eaten these days is in 19th-century British novels.) The reason is that mutton is tough, with a taste so pungent as to be off-putting. Or so I was told. But two days after gnawing my way through that boot-tough steak in Mongolia, I found myself in a camp deep in the Mongolian hinterland, preparing for a feast of mutton – which I presumed would be much worse than that steak. As the sky darkened, I sat in a tent and watched three Mongolian women prepare it in a traditional manner. They threw mutton chops into a huge wok, added potatoes, carrots and salt and pepper, and then opened the door to a wood-burning stove and retrieved several intensely hot rocks, which were tossed in with the same nonchalance as the carrots and potatoes. The rocks were so hot that where they touched mutton bone, the bone burst into flame. Some water was added. A lid came down, and as the mutton cooked, I braced myself for awful meat. But that's not how the mutton tasted. The chops were as tender as any lamb I'd ever eaten, but the flavour was richer, deeper and better.

Mongolian mutton, I realised, was flying below everyone's radar. Despite a world of meat eaters numbering in the billions and communication and distribution networks wrapping the planet like spider's silk, I had to travel to Outer Mongolia to discover the joys of mutton chops. Could the same be true of steak? Was there a land where all the beef was bursting with deliciousness, and the people ate nothing but good steak? Somewhere, there had to be someone who knew the secret.

That's the day my search for steak became a quest. That's the day I set out on a journey that would cover some 60,000 miles of this planet's geography, taking me to seven countries on four continents and sending more than 100lbs of steak into my grateful mouth. That's the day I booked a flight to Texas.

Mark Schatzker's 'Steak: One Man's Search for the World's Tastiest Piece of Beef' (Periscope, £12.99) is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments