The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Gill-to-fin eating: Why we need to widen the net and eat more challenging fish cuts

We only eat about 40 per cent of a fish. But there’s much more to it than that, from the head to the bones to the eyes. Sue Quinn finds how to waste less and enjoy more

The winds of sustainable eating have turned seaward. The nose-to-tail philosophy, coined by chef Fergus Henderson to celebrate cooking all parts of land animals, has become widely accepted.

Now, innovative eco-conscious chefs are diving into the next phase, "gills-to-fin" cooking, using every morsel of the sea’s bounty, not just the prime cuts.

They’re turning bones, heads, offal and other fishy bits that many of us don’t realise are edible into dazzling dishes often more delicious than plates using familiar cuts like fillets.

Crucially, gills-to-fin cooking also reduces waste and stretches precious sea life further, an approach that’s now imperative.

The WWF reports a 39 per cent decline in recorded marine species over the past 40 years, and almost 30 per cent of commercial fish stocks are over-fished. To compound this, so much of what is caught is wasted.

For example, Seafish UK says the fillets on cod and haddock make up just 50 per cent of their weight – the rest is often discarded by processors and used for fishmeal (to feed farmed fish).

“If we want to continue to enjoy these amazing gifts from nature, we’re going to have to try a bit harder and use all of it,” says Jan Ostle, chef proprietor of acclaimed Bristol restaurant, Wilsons.

Ostle uses all parts of fish and shellfish on his menu and is especially passionate about flavourful but pricey turbot.

“Only 40 per cent of the whole fish will end up on the plate once you’ve taken the fillet off, skinned it and removed the bones,” he says.

“Purely from a business point of view, that’s bloody disastrous. But you can make a five course meal out of a turbot if you want to.”

Ostle’s menu is swimming with dishes that utilise undervalued seafood parts.

Turbot served with malted sourdough is made from the heads, for example.

He cooks them gently, then picks out the flesh and presses it into a terrine.

“It’s where the real joy is, the head,” he says. “It’s like the pork belly of the fish – the alchemy of fat and flesh blending together is the really delicious part.”

Fish bones are also smoked over hay to make an astonishingly rich broth, he also dehydrates and deep fries fish skin for a piscatory crackling, and much more.

The perception question: red mullet

A good example of skewed customer perception towards a fish is red mullet. Already in a consumer’s eyes without talking to someone, a conclusion is drawn that it’s mullet and must taste like the earthy, muddy and often "fishy" fish that they may have grown up eating.

Contrary to this, knowing that the diet of red mullet is rich in crustaceans will give us the knowledge that the fish also has a flavour profile reminiscent of lobster, crab or prawn (shrimp). A conversation when purchasing fish with the individuals handling or selling it will help guide you in the right direction. (Extracted from 'The Whole Fish Cookbook')

The deliciousness of these cuts usually regarded as scraps underscores just how much good eating and flavour can end up in the bin.

The thing is, the British have a tricky relationship with seafood.

Amazingly, more than 150 species of fish are caught in waters surrounding the UK, according to the Marine Conservation Society (MCS).

And yet we’re wedded to cod, haddock, salmon, prawns and tuna, which make up about 60-75 per cent of the seafood we eat.

If we’re not prepared to widen the net of fish we eat, will we tuck into the challenging cuts?

Certainly, adventurous food lovers are enraptured by the trend: just peer into Instagram.

Diners at Flor, James Lowe’s new Borough Market spin-off of his Shoreditch restaurant, Lyle’s, adore the scarlet prawns. And the heads are the extraordinary part.

Just as they do in Spain, Lowe grills them, leaving just enough meat in the neck to stop the juices escaping. The result? A flood of flavour when you bite in, which Lowe aptly describes as a cross between foie gras and bisque.

He serves the heads separately to the raw tails, on their own little plate. “It’s a way to celebrate them,” he says. “We want customers to know how special they are.” Meanwhile, over at London restaurant Brat, hake throat is now one of chef Tomos Parry’s signature dishes.

Dry handling

If you purchase your fish whole, ask the assistant to scale and gut it without the use of water.

If this is declined then it is best to scale and gut the fish yourself at home.

It is a common assumption that gutting and scaling a fish at home will cause it to stink for weeks, but if handled correctly, the fish will smell less than one that has already been washed with tap water and wrapped in plastic for the car trip home. (Extracted from 'The Whole Fish Cookbook')

Rich Adams, founder of Forgotten Fish, a gills-to-fin fish supplier, says British restaurants can’t get enough of unused, unknown and underrated cuts at the moment.

“It’s gone crazy,” he says. “I can’t keep up with the requests.” The problem is, most fish processors are set up to treat these cuts as waste, not for human consumption, and he hopes this will change.

Prawn on the Lawn, the seafood restaurant and fishmonger with branches in Islington and Padstow, started serving “weird and more adventurous cuts” a couple of years ago.

“I didn’t do it in an obvious way to start with,” says chef and co-founder Rick Toogood. “A ray wing salad, the cheeks and some meat from the tail poached and shredded.”

But the global conversation about sustainable food has since grown louder and more restaurants are serving unusual cuts. “That’s meant we can push people a little but further into things like collars and heads,” Toogood says.

After eating dishes using both these cuts at Prawn on the Lawn recently I would order them over fillets any day.

The collar (described on the menu as wing because some customers are a bit put off by the term), is cooked on the bone and intensely flavourful and meaty – not fishy at all.

The brill head was also a rich, sticky and delicious feast: grilled on the plancha, then roasted and served with a soy and mirin butter it was a bit like eating a fine piece of pork belly.

Customers often need advice on how to tackle the head.

“We tell them, just go for it, use your hands. Any of the soft bits are good for eating,” Toogood says. Others are a bit squeamish

“People have lost touch with where their food comes from.

If you buy your fish at the supermarket wrapped in plastic, it’s not surprising it’s a bit of a leap to eat the head.”

But he urges home cooks to overcome this and try serving unloved cuts at home.

“The amount of meat you get on a whole cod’s head is probably similar to a whole roast chicken,” he says. “You could serve it as a centrepiece where everyone tucks in.”

If that sounds a bit outré, it’s actually quite tame by the standards of Josh Niland, chef proprietor of Saint Peter restaurant and The Fish Butchery in Sydney, who’s credited with starting the gills-to-fin trend, including ageing, curing and smoking fish for seafood charcuterie.

Niland’s won a brace of awards and a crowd of celebrity acolytes including Rick Stein, Heston Blumenthal and Nigella Lawson.

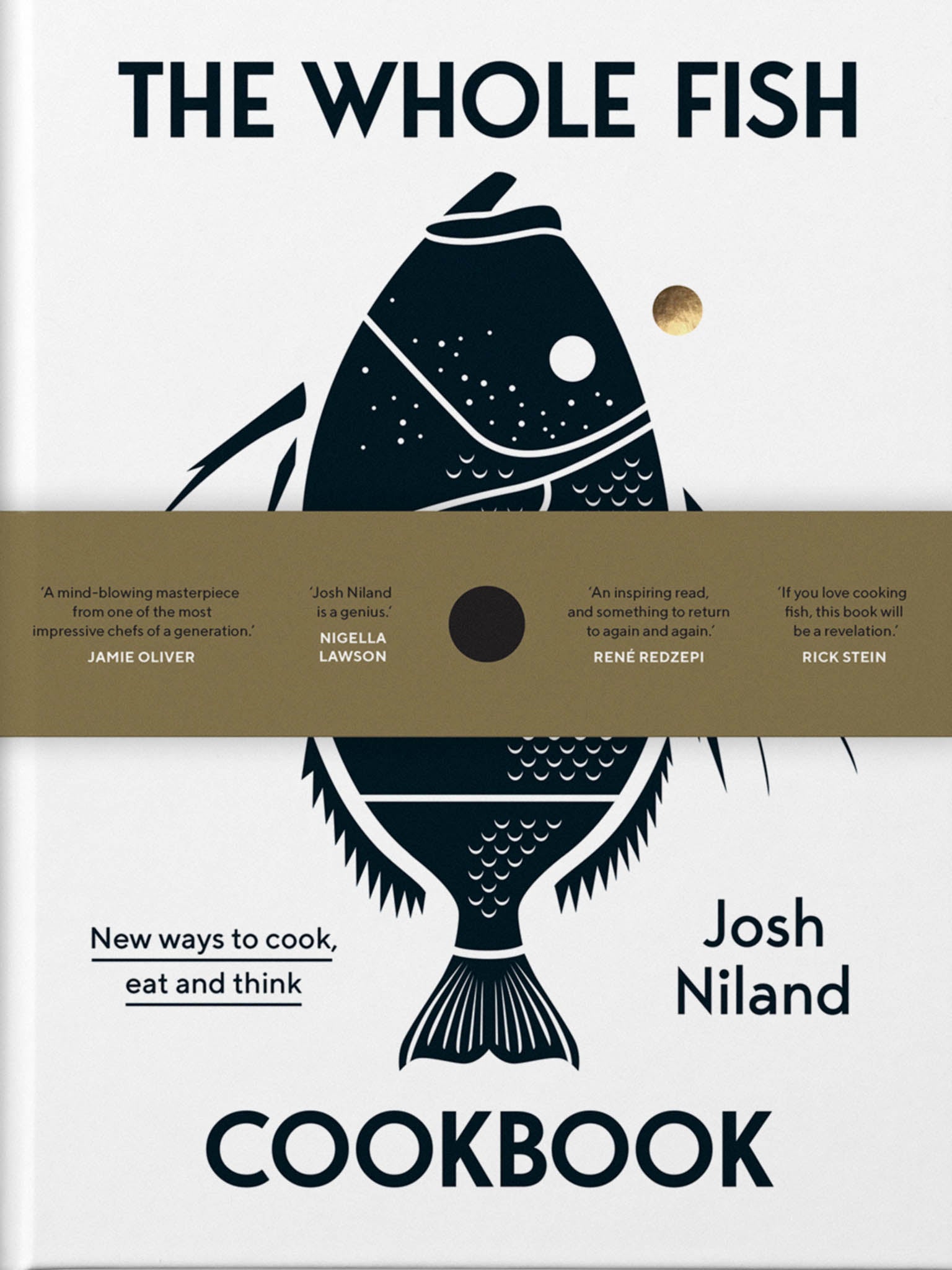

Every chef I spoke to about gills-to-fin cooking can’t wait to get their hands on Niland’s cook book, The Whole Fish (Hardie Grant, 12 September, £25), in which he explores ways to unlock “the untapped potential” of fish.

Think crispy crunchy deep fried fish eyes and scales, sausages made from fish throat and tongue, and black pudding made with fish blood.

Take a deep breath and inhale the sea air, because this is the future.

Sue Quinn is the author of 'Cocoa: An exploration of chocolate'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks