Gadgets: Rage against the machine

Our computers are faster than ever, our phones are sophisticated and broadband speeds are dizzying. So why are we becoming more frustrated by our gadgets?

How many times have you pulled out your mobile phone, hit the Facebook icon and then gnashed your teeth in sheer frustration as the loading logo whirs around for what seems like forever? In the majority of cases, it's only been a few seconds delay and yet you're pulling anguished faces, angry because you just want to see those vital status updates of your friends now... right now... this very millisecond, Goddamit, and waiting for this to happen is just not how things are supposed to be in this day and age.

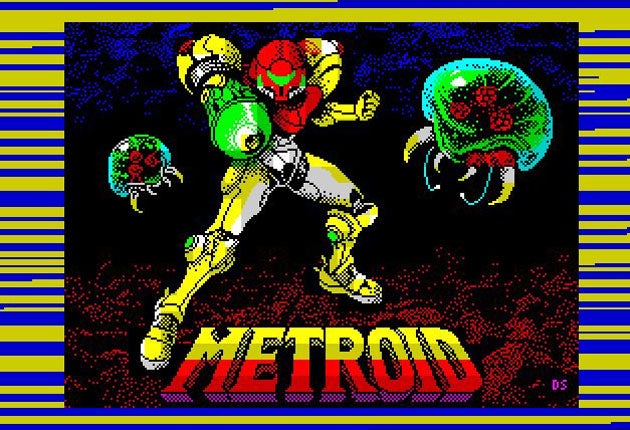

Even though we have never had it so good when it comes to technology, our expectations have been raised to such a point that we would never again put up with the indignities of yesteryear. Many will recall fiddling around with volume controls on their computer cassette decks in the hope that Manic Miner would actually load and not crash after 30 minutes of listening to beeps and crackles.

Today, if we were subjected to such an assault on the ears accompanied by a host of flashing coloured stripes and then ultimate failure, we would throw the computer back in the box and purposefully stride back to the shop, all guns blazing for an immediate refund. Then we would go on Facebook to tell everyone how utterly distraught it has left us feeling.

"I remember listening to Elite load on the BBC Micro for half an hour, only for it to continually fail at 98 per cent complete," recalls Luke Peters, editor of T3 magazine. "But it's how things were back then. I spent years teaching my grandparents to use a VCR and they still don't get it."

When you go back 20 years or so, technology fulfilled basic functions and enabled us to get things done whether it was making toast or ensuring you didn't miss a vital episode of EastEnders. As time has gone on, experts have built on those base needs and refined technology to make it more friendly for users. So you can buy a toaster which propels your warm bread through the air and on to your plate, negating the need to actually handle this time-zapping process yourself, and you can set Sky+ to ensure you never again lose tracks of the comings and goings in Albert Square ever again.

Failure is not an option. Even if things do go wrong, we want the comfort of a safety net, either that all-important undo function or some kind of recovery option. We are at a stage where we can indulge and enjoy the luxury of our gadgets and not worry about having to tinker under the hood with menu after menu of settings just to get things moving.

"Today's technology is easier to use today than it ever has been," says Peters. "But I also believe it's a generational shift. Many people under 30 have been surrounded by some form of technology all their lives. Whether that was a VCR, digital vending machine, microwave or school computer, this continual relationship has meant that interfaces are naturally more instinctive. This has reduced the fear of buying technology and using new gadgetry."

One of the major pioneers has been Apple. It dropped the 3.5-inch disk drive in 1998 and believed the internet would be better placed for file saving and sharing. Its iPod and iTunes have revolutionised music, making the process of downloading tunes and selecting them on a portable device far easier than anything that had been tried before. The iPhone killed all previous attempts at creating internet experiences on mobiles by offering something that worked incredibly well and intuitively. And as for the App Store, well that was the icing on the cake.

All of this has helped changed our attitudes towards technology – now we expect gadgets to be picked up and used by anyone regardless of age or technological preconception. Manufacturers realise we want technology to work for us so they have also altered how they design their own products. Software developers put the user at the forefront of their minds.

"Mobile devices are used by people who are at different levels of technical experience and many of them will have zero technical experience," says Matt Legend Gemmell, who produces software for the iPad, iPhone and iPod Touch. "They're also used on-the-go and for when time is precious like finding out when the next bus is due. So the maximum tolerable frustration level is very low indeed, and users will just delete your app away rather than persevere if it isn't designed correctly. User friendliness when designing software isn't an optional extra."

Gemmell says developers have to think like a regular person rather than an engineer and he believes it's less about computer science and more about empathy and social psychology. "The key point is to break down your assumptions about how the user will see the software, and then identify which of those assumptions apply to people in general, and which actually only applied to skilled and technical people," he adds.

The drive to ensure technology makes our lives easier without any of the frustrating fiddling of the past can be seen starkly with peripherals. It used to be easier to get warring nations to talk to each other than it was hooking a printer or scanner to a computer and actually getting it to work first time. Grinding noises, tractor feed paper jams and incorrect drivers made it easier to grab a sheet of A4 and write things out by hand. It was a surprise for many, therefore, when the iPhone's 4.2 update introduced AirPrint and, when hooked to the right printer, it worked within minutes.

"People expect technology to just work, and that applies to printers as well," says Sarah Fortuna, of Hewlett Packard. "Reliability and easy printing are still very important, as is making printing relevant to our new on-the-go lifestyle. But I don't necessarily think people were tolerant of poor technology in the past; it is only in hindsight that what were considered to be groundbreaking solutions and technical wizardry back then now look arcane and clumsy versus what is offered on the market today."

And yet for all of this hand-holding, there is a sense that we may be losing something rather vital. The hours and days spent with our noses in the troubleshooting sections of manuals, the pounds forked out speaking to "experts" on technical helplines and the hair lost from getting close to resolving an issue on a forum only to find the thread tapers away have actually made us rather knowledgeable since we've often had to seek our own cure.

But in producing computers as usable as a hammer, there is less chance of people chipping away and exploring their machines in hope of a solution.

"There will always be the niche 'open-source' ambassadors of technology vying for as much user freedom as possible," counters Peters. "But if simple, straightforward technology means that it can enrich our lives and increase efficiency in everything we do, then I think that's a good thing. It is, and still will be, possible to break free from the constraints of certain technologies for many years to come."

But does it increase efficiency? By becoming easier to use, the instant nature of technology can put a different kind of strain on our minds. Robert J Edelmann, Professor of Forensic and Clinical Psychology at Roehampton University, says we don't only expect immediate communication but instant results, instant replies and instantly delivered paperwork. And whereas we would expect a video game cassette to take half an hour to load in the 1980s, we don't always know how long something will take today – a webpage could come up instantly on a broadband connection or take seconds on a mobile. People are unsure as to how patient they should be.

"There is a growing awareness in the psychological world of the stress imposed by new technologies," Prof Edelmann explains. "The inability of users to switch off can cause an inability to separate work and home and there is a constant need to check and re-check Twitter, Facebook and so on. While in some ways instant communication makes life easier it is clearly important to be aware of the potential downsides. And when gadgets crash, there's no signal or a virus strikes, it becomes a highly stressful situation."

One that looks set to get worse, by all accounts, given that technology is likely to get even easier to use in the future. The emphasis on making ever-faster devices – which has been the hallmark of computing from the earliest of years – has caused us to overshoot our basic needs in this respect so more attention will be paid to user experience as time rolls on.

"The first thing you do when you identify a need for a computer is to get it to do your basic job according to how difficult it is to use the damn thing," says futurologist Ian Pearson.

"The luxury of making the process easier to use comes second. But we're at the stage where the hardware is fast enough and of sufficient quality to be able to produce great user-friendly software. It requires a huge amount of number-crunching and lots of very clever software to do it which is quite paradoxical but we can be sure technology will continue to get easier and easier and better and better."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks