iPad Pro: How Apple made its new tablet – and what exactly it is

In an exclusive interview, the company’s marketing and hardware chiefs explain the creation of the tablet – and why they don’t want you to call it that

Halfway through the most recent Apple event, a man appeared to tear off his face. Underneath was Tim Cook. He turned on an iPad, into which he had just dropped a computer chip he had stolen from a Mac.

Cook’s special effects were impressive, and so was his unexpected embrace of his role as an action star. But when it comes to hidden depths and mistaken identities, he had nothing on the processor and tablet he had just been seen sneaking in to play around with.

That chip was the M1: a processor made for a Mac now stolen and dropped into an iPad. And it means the iPad Pro is now a tablet that some have argued is now seemingly too powerful – so fast it leads to questions about what it is really trying to do.

When the Apple engineers did the work that allowed Cook to rappel down and change up the iPad Pro once again, they were kicking off yet another instalment in an ongoing identity crisis that people have been having on behalf of the iPad since before it was first released in 2010.

But Apple’s executives – its marketing head Greg ‘Joz’ Joswiak, and its hardware chief John Ternus, who speak toThe Independent soon after the iPad’s unveiling – say they know exactly what the iPad is. It’s just that it might not be what you think.

Joz and Ternus talk toThe Independent in the wake of a busy event that saw the release of a whole host of new Apple products: an iMac with a redesign and the introduction of the M1 chip that first arrived late last year to zealous praise, AirTags for tracking lost devices, a new colour for the iPhone and more.

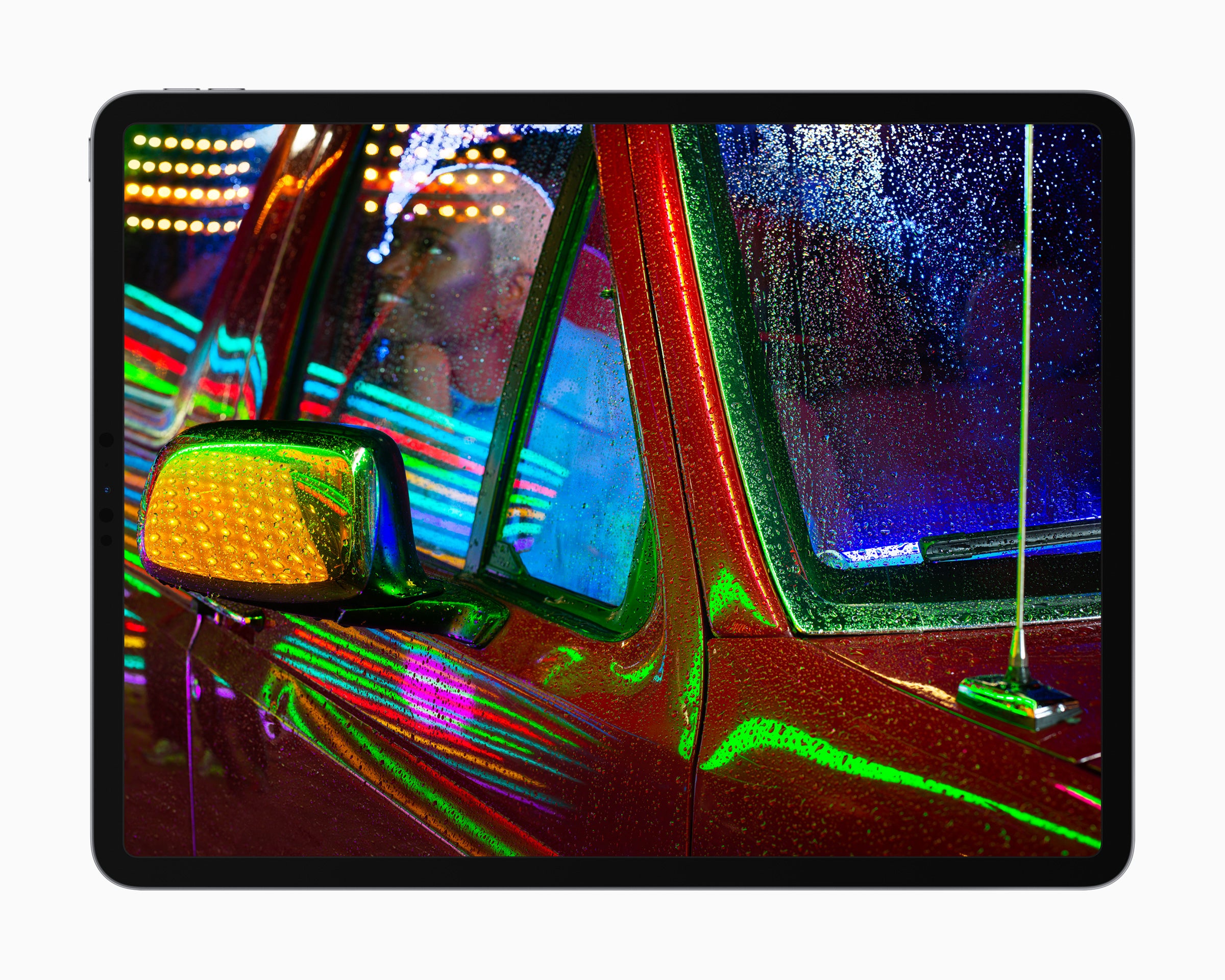

But the headliner was the iPad Pro, which as well as the M1 chip also includes a new miniLED display that it calls Liquid Retina XDR, 5G, vast new storage options that go all the way up to 2TB and new connectivity options including an improved Thunderbolt port. The additions address many of the complaints about the existing iPad Pro, and also make it look a lot more like a Mac computer, or at least a rival to one.

The iPad’s history has seen it accused of a lot of being a lot of things in disguise. At launch it was just a big iPhone, simply a content consumption device that had grown too big; nowadays, it is more often accused of being just a flash Mac, part of Apple’s plan to supplant its more traditional computers when the iPad grows big and capable enough.

Many of those who follow the latter story argue that Apple’s real plan is not to keep the two devices around but instead to mash them together into one device: a touchscreen Mac, or an iPad that can run macOS, or perhaps both. Apple has repeatedly denied either, with software boss Craig Federighi tellingThe Independent late last year that he was surprised by stories that suggested a new design of the desktop operating system was really getting it ready for touch.

But the new iPad Pro is a merger of a kind, even it is the exact opposite of the one that usually grabs the headlines: the new tablet is running the same chip as Apple’s newest computers, and borrows from other Mac technologies like the Pro Display XDR, and so it is not the software that has merged but the hardware. It would seem to be enough reason to start another identity crisis – but Apple is firm that it knows exactly what the iPad is, and what it is not.

“There’s two conflicting stories people like to tell about the iPad and Mac,” says Joz, as he starts on a clarification that will lead him at one point to apologise for his passion. “On the one hand, people say that they are in conflict with each other. That somebody has to decide whether they want a Mac, or they want an iPad.

“Or people say that we’re merging them into one: that there’s really this grand conspiracy we have, to eliminate the two categories and make them one.

“And the reality is neither is true. We’re quite proud of the fact that we work really, really hard to create the best products in their respective category.”

(Joz, however, is reluctant to name the category he’s talking about: he jokes that he “can’t even stand using” the word, because the “iPad is better than tablets”. “I hate to diminish it by calling it the category name,” he says.)

“Customers agree with us, right?” he says. “We have the highest customer satisfaction, again for each of those products in their category.

“And they’re voting with their pocketbook, right? Both these categories have grown, but iPad and Mac have greatly outgrown their category. And so that’s what our strategy is: create the best product of both.”

On that point, John Ternus jumps in to correct “another part of the narrative that is very untrue”.

“We don’t think about well, we’re going to limit what this device can do because we don’t want to step on the toes of this [other] one or anything like that,” he says. “We’re pushing to make the best Mac we can make; we’re pushing to make the best iPad we can make. And people choose.

“A lot of people have run both. And they have workflows that span both – some people, for a particular task, prefer one versus the other.

“But we’re just going to keep making them better. And we’re not going to get all caught up in, you know, theories around merging or anything like that.”

While many of the workflows are the same, it’s largely touch that continues to distinguish the two devices. Ternus also points to the Apple Pencil – which does not have any kind of analogue on the Mac – as well as the fact that the iPad includes better cameras and augmented reality tools that don’t or can’t feature in its bigger siblings.

But there are notable things that the iPad can’t do, however, and they are not to do with hardware capabilities. If there has been a concern raised about the new iPad Pro, it is certainly not that it is not fast enough. Indeed, it’s the opposite: that the computer has such outrageous amounts of speed but with nothing to actually use it on.

When Apple demonstrated the M1 in the Mac, for instance, it did so in part by using its Pro apps: showing the vast number of tracks that could be used in Logic, or video streams in Final Cut Pro, or the speed with which it would compile an app in Xcode. That is not possible with this iPad, not because it lacks the speed – it is, theoretically, identical in that respect – but because those apps don’t exist for the iPad at all.

Likewise, the display takes the best of the Pro Display XDR that came with the Mac Pro – and cost as much as £5,499, plus a stand that costs £949 – and makes it available in a tablet that sells for less than a fifth of that. But the stunning brightness and colour accuracy of the original display was marketed largely as a way for video creators to get the best view of their work; on the iPad, again, there is no Final Cut Pro, and other big video editing apps are yet to make the leap too.

The iPad is almost too fast for its own good, though when this is put to Joz he quips back that nobody has complained about a device being too good. But it’s at least another potential question about the iPad’s identity: what’s an “outrageously capable” iPad Pro, as Joz describes it, without a full suite of professional apps to use it with?

It would make a lot of sense to presume that we’re seeing hardware that is anticipating updates to Apple’s software, and it would certainly be conceivable that at least some of those apps are coming later, perhaps at its WWDC conference in June. But that’s remains no more than a presumption, for now; Apple is not announcing anything about the future of its own apps on the iPad platform, even when asked.

Instead, Joz refers to the extra headroom that the power gives developers; this is a computer aimed at pushing the envelope and the boundaries, making extra space that developers can find new ways to occupy with their own apps.

“We provided that performance even before the need was there, if you will,” he says. “When you create that capability, that kind of ceiling, developers will use it. Customers will use it.

“It needs to exist first, right? You can’t have an app that requires more performance than the system’s capable of – then it doesn’t work. So you need to have the system be ahead of the apps.

“And our developers are pretty quick about taking advantage. It isn’t like, it languishes for years. Trust mem the Adobes and the Affinities and all the people creating pro stuff – this is like music to their ears, they need this kind of power to have more capability to do more features.

“And what a great thing for our customers, by the way, to know that they can buy a system today that still has headroom. It isn’t going to be immediately obsolete, which is often the case if they buy an inferior product – it’s obsolete from the day they bought it. Whereas, you know, iPad Pros continue to have headroom.”

(When asked again, the morning after the reveal, whether Apple is one of those developers that is planning to take advantage of the extra headroom with its professional app, Joz jokes that he’s not going to let something like that slip out.)

Until now, Apple’s iPad chips have followed a fairly reliable pattern. Each year, a new version of Apple A-series processors is released with the iPhone, and when an iPad Pro comes out it gets that same version with an “X” in its name, to indicate that it is a much faster variant built for the larger device.

Apple has spent the last year breaking with a lot of reliable patterns, and the iPad Pro is the latest. Instead of the tablet getting its own chip – which would have been expected to be the A14X, after the A14 that arrived with the iPhone 12 – there was the M1, dropped in by Tim Cook during that action sequence.

The M1 is itself similar to the A14, and they are all part of the same family; the great departure of last year’s Macs was to bring the Apple chips that began life in its mobile devices in its larger computers, too. But, as the “M” in its name suggests, it was made for its Macs, and to see it dropped into an iPad was unexpected.

“Part of the beauty is just: could you imagine a chip before M1 that you could take out of a desktop and put into an iPad form factor?” says Joz. “This is the same chip, just like you saw in the video, that we could pull out of a Mac and put into an iPad. That just, to me – I’ve been around in this industry for so long – is not somehting you could have contemplated before.”

While it might appear surprising, the decision to put it into that tablet was part of the principle that has always applied to the line-up, says Ternus.

“The best Apple Silicon that we make goes into has always gone into iPad Pro. And M1 one is the best Apple Silicon that we make.

“It’s an incredible collection of technologies. You know, it’s not just the CPU and GPU performance. It’s the ISP, it’s the neural engine, it’s the Thunderbolt capability. It’s all of these things. So it was just natural that we would want to be able to bring all of that capability to iPad Pro.”

In the most superficial way, this is the most Mac-like iPad there has ever been. You could already slot it into a keyboard to turn it into something like a laptop; now it has not only the Mac’s M1 chip, but display technology taken from the Pro Display XDR and the speedy connections, chunky memory and vast storage that have long been the preserve of its older siblings.

But the big challenge will, inevitably, be shrinking those down; one of the notable things about the iPad Pro is that it includes features that initially were the preserve of the biggest Apple devices, but squished down into a device that is little bigger than its relatively small screen. It doesn’t only have to be small but mobile, too, built for a device that has to run on its own battery and be carried around in a bag.

And there is no way that is more true than that display itself, which took technology that until now was available only in the much bigger Pro Display XDR – and made it even better.

“Shrinking it was a huge undertaking,” says Ternus. “If you just look at the two products, obviously the iPad is a lot thinner than a Pro Display XDR, and the way the architecture works – you have the LED backlight behind the display.

“As you shrink it down, you necessarily need to add more LEDs; you need to kind of increase the density, because you don’t have as much room for mixing the light and creating zones.

“From the very beginning it was: how do we create a backlight with sufficient density? So we had to design a new LED. We had to to design the process for putting down 10,000 LEDs on this backlight in this incredibly precise manner.”

(At this point, Joz cuts in to stress how big that number is: the previous iPad Pro had only 72 LEDs, he notes. “It’s pretty mind-blowing,” agrees Ternus.)

“You have all these LEDs but then you’ve got to shape the light, you’ve got to mix the light, and you’ve got to create this incredible uniformity we always have in our pro displays and our iPad displays.”

When pressed on how it is possible for a device to be shrunken and squashed to such a degree, both Ternus and Joz point to Apple’s investment and belief in its platforms and its engineers, as you might expect. But they are keen to stress also that they have the benefit of working on these problems as a whole organisation, and that the technologies are developed in-house – which is to say, specifically for a given device, whatever that device is.

“We’ve seen a lot of other people try to build products by just pulling stuff off the rack,” says Ternus. “Even from an [operating system] standpoint, just kind of pulling pieces together to create something that is not super compelling, where we built – I mean, we have an iPad OS, right, it’s focused on iPad, we put that effort in.”

In early April, as the full reality of the pandemic began, so did a realisation that the front-facing cameras inside of our devices weren’t really up to the job of becoming our portal into the world outside. In stark contrast

Apple started to address that problem in November, when it released its new M1 Macs. The camera itself was unchanged, but the additional image signal processing power in the chip meant that the computer did what it could to improve the look of that picture – reviewers agreed, though only somewhat, and the cameras continued to have room for improvement.

The new iMac, introduced just before the iPad Pro, also does what it can, with the addition of a new, larger sensor aimed at giving better performance, particularly in low light, and the addition of the M1 for that extra power too.

But it’s the new iPad Pro that appears to be the first Apple device truly built for an era of working and socialising remotely. It finally receives a true upgrade to the front-facing camera, with a much wider lens – and the ability to track people around, keeping them centred in the frame.

“One of the things that I found really cool about it is – spending all this time in these meetings, you sit a lot,” says Ternus. “And it’s so liberating to be able to just stand up and stay framed in the image, and stretch and move around and sit down,” he says, noting that it is a neat way to still be able to close rings on the Apple Watch.

“And one of the things I found sometimes is in group scenarios – you may be FaceTiming with your family and be able to get the family in the frame, or those kind of things, I think are going to be really, really big and powerful. It’s certainly an amazing technology for the times we’re in.”

A similar feature is available in other devices like Amazon’s new Echo Show, which literally follows you around with a swivelling motor in its base, or the Facebook Portal. (The Portal has also struggled with the fact that it is a face-tracking, always-there camera made by Facebook; the initial version was launched in the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, and concerns about how the data is used have haunted it ever since.)

But Joz says that the company went to an effort to ensure that the feature was done in an “Apple way”. He describes the panning and zooming as “cinematic”.

“Instead of seeing these harsh movements or cuts, you almost don’t notice it happening, just like you wouldn’t on television. It’s so pleasing to your brain that it works quite nicely.”

The idea, it seems, is that the object fades away – that you don’t see the swivelling camera or the swift zooming, but the person it is focused on. The iPad disappears, in what is perhaps the ultimate disguise.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks