Apple shows off robot for tearing down iPhones as it reveals new recycling programmes

Daisy, one of Apple's most valued resources, eats iPhones. She's very, very good at it, and getting better: trained with a precision that would have been unimaginable just a few years ago.

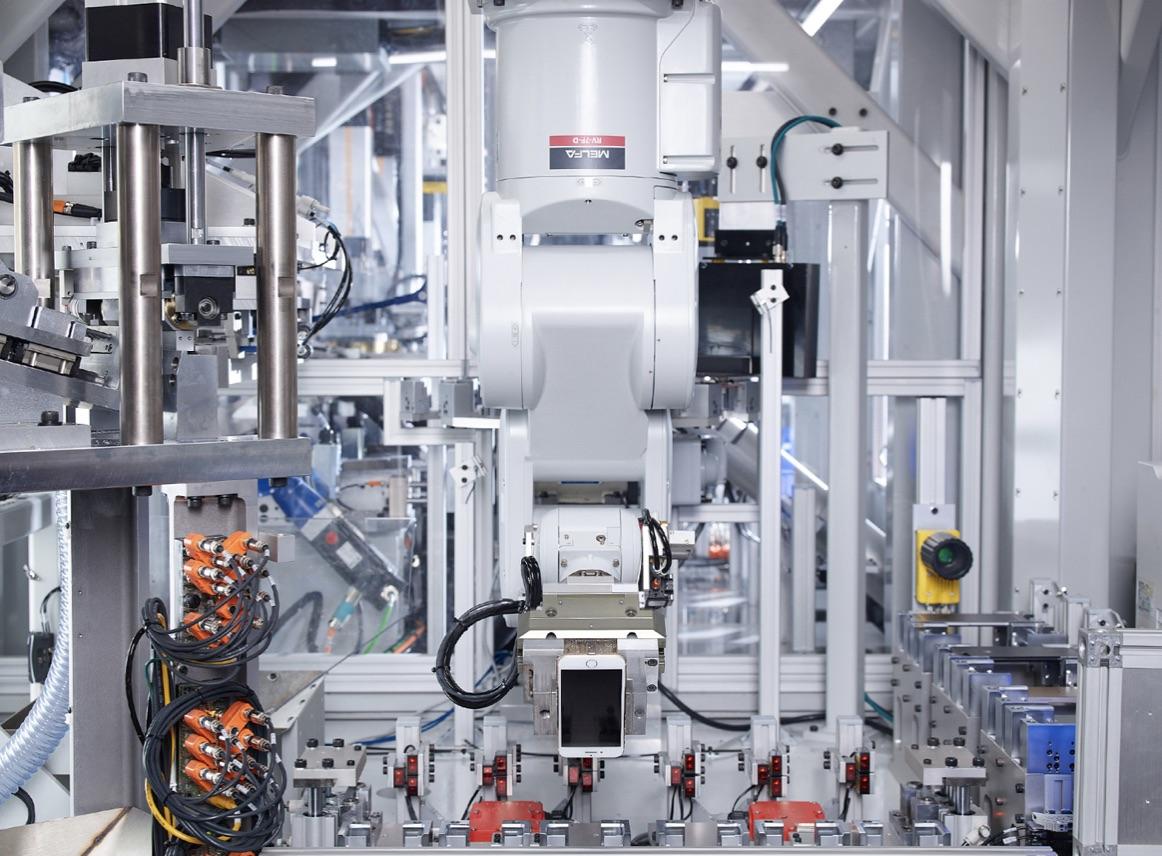

She is a robot, with a variety of tools built to rip the phones apart. That includes, for instance, a tool that can chill phones down so that the battery holding the glue inside becomes brittle, and it can be knocked out with two aggressive bangs; precise pins that can pick the display off the housing that surrounds it; drills that can punch into the phone and drive out the things that might make it difficult to recycle.

It won't surprise anyone to hear that Apple is pretty good at making iPhones. But what's less well known is just how good it is at breaking them apart, too, with all of the same precision and thoughtfulness.

Daisy, the robot built to do that, is an efficient and developed iPhone destroying machine, and she is being revealed in detail by Apple for the first ever time. It is doing so as part of a broad effort to expand its recycling programmes, and to make its iPhones and other products even more sustainable.

Because Daisy doesn't chew up iPhones for the sake of it. In fact, it's more accurate to say she regurgitates them: by taking them apart, Apple can pick out the particular materials that are used to create the phone, and then use them again.

Daisy has been developed by engineers that form Apple's newly announced Materials Recovery Lab, a 9,000 square foot facility in Austin that looks to create new and more innovative ways of recycling, and she follows a predecessor called Liam. (Apple refers to Daisy as she, and the company hasn't revealed the origin of the name.)

That Materials Recovery Lab is aimed at creating the same kind of innovation that has characterised everything from the smallest wireless earphone to the grand new Apple Park building that serves as its headquarters. But it also represents a marked change in philosophy: the company plans to be open about what goes on there, with the aim of encouraging partners and other companies in its sector to advance the efficiency of recycling processes.

Apple has built the lab and does such work to help achieve its aim of a "closed loop" manufacturing process, where all the materials used in its devices will have come from recycled products, rather than from the ground. And it is getting closer and closer to that goal all the time.

Daisy has already eaten up about a million devices, and is getting through them quickly. Each of the two robots the company runs – one located in Austin, Texas alongside the Materials Recovery Lab that works on such innovations, and another in the Netherlands – can now take apart iPhones at a rate of 1.2 million per year.

Still, most phones that are traded in don't go to Daisy, and that's the way Apple likes it. If you trade in a phone now then it will probably be refurbished and pushed back out into circulation, ready for someone else to use it. That happens to eight out of nine of the iPhones that arrive at Apple.

And many phones still don't get traded in, despite Apple's best efforts.

The company offers financial incentives to encourage people to do so – with a Trade In programme that lets people send in their old iPhones or even other devices, and get up to $500 off a new one, that has now been expanded to Best Buy in the US and KPN in the Netherlands. But it also wants to encourage a deeper shift in the way people want to think about their devices, too.

"What you can do is get in the habit," Lisa Jackson, Apple's vice president of environment, policy and social initiatives tells The Independent. "Your old technology should come back at the time when you're looking for new technology.

"If we all just got in that habit, I think over time we would start to see much higher recycling rates for products."

Jackson and Apple know that a lot of people are holding onto their phones for a long time – passing them up generations to parents or grandparents, or down to kids.

The company doesn't want to stop that. "But at the very end, if you can get it to Apple, we will then use it to make new products. That's the journey here."

Some have argued that fewer phones should get to this point – that Apple's phones should be easier for their owners to repair themselves, as part of a right to repair philosophy that has grown into a movement. Apple says that it is doing what it can to make those repairs easier, with a network of 5,000 Apple Stores and official service providers, as well as a new iPhone screen repair method that allows many more shops to offer it.

But some of these devices are simply beyond repair: those that do reach the very end of their life, the unlucky one in nine that arrives to be torn apart, is definitively finished. They tend to have undergone some significant damage, the kind of drastic event that makes them no good to anyone as phones – but still very useful as a collection of rare materials.

Demonstrating just how useful it is to have those materials back, Apple already uses entirely recycled tin in a key component in the main logic board of 11 different products.

And last year Apple last year introduced a new MacBook Air – and in the same spirit of innovation said it was entirely made of recycled aluminium, giving it nearly half the carbon footprint of its predecessors. Now aluminium come through Apple's Trade In programme is being remelted into the enclosures for the laptop: your new laptop could be made of your old iPhone, after a little input from Daisy.

Apple is part of this process right from the beginning to the end – from the beginning moment, when it is just an idea in a designers' head, to its eventual demise, at the hands of Daisy – it can ensure that this kind of end-to-end reuse is possible.

"The work we do on recycling informs the work that happen throughout Apple," says Jackson. Designers and engineers will visit the materials laboratory to talk through products they're thinking of working on to make sure they adhere to a principle that has become as core to Apple's design process as innovation and delight: that they, as Jackson puts it, "use what we need to use and not one atom more".

In doing so, Apple has shown that what works is pursuing a "full organisational effort", says Jackson, so that everyone working in the company is committed to recycling. If everyone is working towards that goal – everyone designers of the products, the people who sell them in retail stores, and those in marketing who tell the world about them – it helps ensure that everyone sees the value in the circular economy, she says.

Recycling consumer electronics efficiently has proven to be difficult. They are full of a variety of materials: not just the rare earth metals that allow for the hi-tech features seen in iPhones and other advanced products, but also a host of more prosaic materials like plastic.

That variety has made them difficult to sort out and separate, which is necessary because each of them has to be recycled individually. The recycling industry uses a host of different tools to do so, from shredding them up into small piece of aluminium to vibrating them over a huge industrial sieve to separate larger parts from small.

That is, however, as inexact as it sounds. And imprecision is a significant problem when recycling, since any material is only as good as its worst constituent. You might have a whole phone's worth of aerospace-grade aluminium, for instance, but if that is contaminated with a much less pure alloy, it drags everything down to that level.

It was that problem that led Apple to put together the MRL, and to develop the technology that sits inside of it. The work started with the creation of Liam, the first of Apple's iPhone-destroying robots.

Liam was impressive at the time. Despite not having any kind of sight, he used impressive automation to be able to take the phone apart. He would unscrew an iPhone's screws, for instance, dropping them out so that the aluminium they had been attached to was ready to go off for recycling.

Daisy builds on that work, though she is much more impressive. She's also more aggressive.

While Liam's precision unscrewing was smart, for instance, it meant that he had to be ready to find the exact place to drill, and that he had to hope the screw he was taking out was not corroded or otherwise difficult to grab. Daisy, on the other hand, has no such qualms: she works on the principle of destructive disassembly, truly tearing apart the phone with a precise force.

Rather than picking out screws, she blasts through them. Instead of grabbing off a screen with suction, she reaches in and pries it off. It is like swapping out your housecat for a tiger.

Liam's problem was also that variation proved a major limitation; things had to be in the right place for him to rip them apart. Daisy's approach makes her much less choosy – and she can now rip apart 15 different models of iPhone, going all the way back to the iPhone 5, long before Apple had begun this kind of recycling process.

Each of the different parts plops out of Daisy at different stages of the process. People are ready to grab them and put them in their right place, ready for recycling – the facility is full of boxes known as gaylords, with one crate full of iPhones drilled with holes, another the camera module, and so on.

They're then passed back up the manufacturing process. The batteries are grabbed, combined with scrap from manufacturing sites, and the cobalt is used to make new Apple batteries.

It means your old iPhone could also be your new one. And that's the loop Apple aims to close up: materials going round and round, used by you and then bashed out by Daisy, creation and destruction all at once.

"There are labs for all kinds of things at Apple – really amazing, impressive labs where you walk in and feel like you're in the future," says Jackson. "We expected the materials recovery lab to be the same way: the future of recycling will at least in part be out there as well."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks