How the Government's plan for autonomous vehicles could be driving us towards a dystopian future

The government is spending hundreds of millions of putting self-driving cars on the streets. But it isn't spending enough time or money on getting those streets ready

The British Government is spending unprecedented amounts of money on encouraging the development of cars that drive themselves. But the UK is little prepared for the disruptive and potentially devastating changes that such cars could bring to our streets, experts have warned.

While huge amounts of work is being done in the UK and elsewhere on such technology, towns and cities are continuing to work largely as they have with private, driven vehicles – by both governments and private car and tech companies – little is being done to change the cities they will drive around. That could become a problem if autonomous vehicles truly take over, as the government has both predicted and supported.

That’s because little is being done by either the Government or other bodies to ensure that the country is ready to embrace the challenges brought by such technology. Such challenges range from the everyday but significant problems of road space to the more unusual but no less damaging problems of terror and hacking attacks, experts warned.

The Budget laid out in November includes a full £1bn for high tech projects. That includes £75m to be spent on artificial intelligence, £400m for electric car chargers and £100m on clean car sales. All of that will pay for the future where autonomous vehicles are on the streets by 2021, the Government claims. Chancellor Philip Hammond backed that up with a series of public appearances during which he backed driverless cars.

The money is praised by the many experts who fear that the UK, and the rest of the world, needs to prepare for major changes coming to our streets. But it isn’t enough, many experts also say, and the Government needs to reconsider the streets themselves, and how they are able to deal with self-driving cars.

Hammond and his ministerial colleagues haven’t discussed how they see the future of the roads themselves, but have made much of the money they intend to spend and the future they intend that investment to bring about. However, some have claimed that the government’s hope of autonomous vehicles on the road by 2021 isn’t possible – potentially meaning it is failing on both counts.

“Hammond is attempting to position the UK as a hub for automotive innovation, which we definitely can and should be,” said Chris Green, chief risk officer at consumer car management company Regit. “Unfortunately, his completely unrealistic timescale renders the statement relatively useless. While there has been testing by the likes of Jaguar Land Rover and Oxbotica, the UK is very much lagging behind the world’s major players such as Google’s sister company, Waymo, who are currently undergoing level 5 testing.

“When it comes to autonomous technology there is a great deal that needs to be done in terms of regulation, insurance, infrastructure and education before driverless cars can be a legitimate and feasible option for the UK’s roads – and £540m for research and infrastructure will barely scratch the surface.”

Philip Hammond, for his part, is clear that self-driving cars are coming and that people need to prepare for them. He has given repeated warnings to workers that they need to retrain, though said less to town planners and other important people involved in getting cities rather than their workers ready.

“It will happen, I can promise you,” he told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme soon after the Budget. “It is happening already ... It is going to revolutionise our lives, it is going to revolutionise the way we work. And for some people this will be very challenging.”

The Government seems to embracing that challenge, encouraging people to get ready for the new world. But that instruction to change mostly seems to be issued to other people – the Government is still being urged to think about the various problems that will arise from the technologies they are investing in.

“It is crucial that we begin to address these issues today,” said Russell Goodenough, client managing director for the transport sector at Fujitsu. “Driverless cars could boost UK productivity by enabling employees to work while commuting, as well as reducing accidents on the road and reducing the amount of land needed for parking.

“The Government’s investment in the technology is to be welcomed, and it’s up to everyone in the transport sector to come together to agree exactly how this technology will work in the UK.”

“My concern is that, as with when private automobiles came on the scene back in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, there wasn’t really any regulations that came out alongside that, and we just kind of adopted this new way of getting around wholesale, without thinking of the spatial implications,” says James Harris, policy and networks manager at the Royal Town Planning Institute. “How did this change where we live and how we work? We aligned that completely around the car and down the line that led to a million different problems.”

Some of those same problems might already be forming. If we don’t think radically about how to make the most of autonomous vehicles, we might simply use them as a way of continuing the dominance of the individual, personal car – something that is likely to further increase the current problems of public transport and of inequality.

“The dystopian future you could head towards is everyone can afford it substitutes their vehicle for an autonomous vehicle at great expense,” says Harris. “You have the same amount of people in the same number of cars – and with the exception of moving slightly quicker, you have the same problems of car dependent sedentary lifestyles.

“It might even encourage people to live further from work because it’s more pleasurable to commute. But then you’re more likely to have people on the road in their private cars.”

Most public bodies agree that work needs to be done to avoid that nightmare future. But the actual work to get cities ready for that will be expensive and detailed – far more costly both in time and money than the £1bn and four-year budget given to the UK’s autonomous vehicle industry by the Government.

Perhaps the most deep and detailed work going on at TfL is a long way from completion. The organisation has ongoing research being conducted by two students at MIT, due to be completed in summer 2018, it revealed in response to a recent freedom of information request.

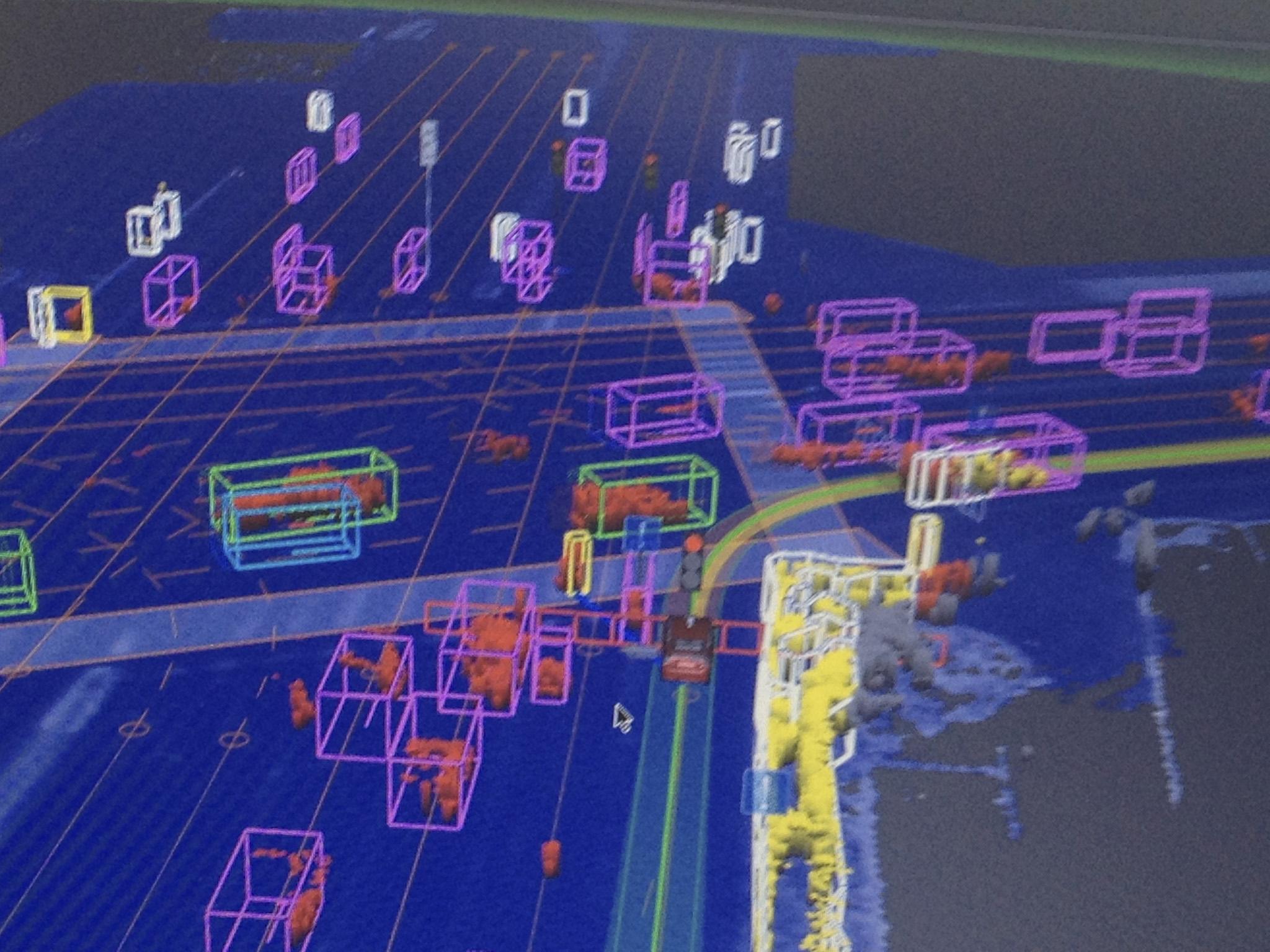

For now, the most recent consideration of autonomous vehicles by Transport for London – and apparently the only time TfL has deeply considered such issues, according to an FoI request – was set down in a discussion by its performance panel in July. It noted that the “rapid and accelerating pace of change in technology (from vehicle sensors and connectivity, to analytics and artificial intelligence) and the emergence of the ‘sharing economy’ means that new mobility business models are coming to the transport sector”, and said that its Transport Innovation Directorate was charged with identifying both the positive and negative outcomes of such changes.

It noted that connected and autonomous vehicles could change cities for the better or the worse, and went on to lay out both situations. It didn’t comment on or commit to either.

Potential problems include the potential for easy car travel for people without a car or a license that would then stop them from using public transport; an increased use of them for the last mile of the journey that would discourage people from more active forms of transport; more congestion being caused by more road traffic; and cyber-security, which could bring a whole new dimension to the risks of car travel and security, particularly if vehicles have progressed to full automation where no driver input is required”, including to buses and freight vehicles. But benefits might include easier travel for the elderly and movement impaired; improved road safety; better use of the limited road space in London; and improved transport for everyone, since they could provide a form of transport that is ruled out for most people.

Despite giving a concise summary of the potential problems and benefits – and a less concise round-up of the various ways that London has been internationally leading in the testing of new forms of transport – TfL doesn’t yet seem to have come to any clear conclusion on autonomous vehicles. It will “continue to stay abreast” of new developments, it said.

The Mayor of London’s transport strategy, which was also published over the summer, came to much the same conclusion though offered far greater detail on the principles that will guide that work. It noted in detail the kinds of changes that had happened over recent years and will happen in those to come, and concluded that it “is essential that London is prepared”.

But, like TfL, its proposals mostly focused on ensuring that the right principles were in place before the technological change comes. It set out a series of principles including moving people away from car travel, complementing the public transport system, opening travel to everyone, cleaning the air and ensuring that space was used well. It promised to take “a safety-first approach”, and committed to “adopt an appropriate mix of policy and regulation to ensure connected and autonomous vehicles develop and are used in a way consistent with the policies and proposals of this strategy.

All of this work on both principles and practical application will be important because autonomous vehicles will bring with them a regulatory challenge unprecedented in public transport. If used well that might be a similarly grand opportunity, but it could represent a major challenge too.

“My thoughts on autonomous vehicles in a big city is that you would probably want them managed by a city wide transit authority, like TfL,” says Harris. “But you would want them only to be implemented in the city where they have value.

“So you’d still have bike networks, paths, tubes, but also fleets of autonomous vehicles that could help people get from where a tube line ends, to provide that last mile and get you from Tube stop to your front door.”

That sounds a little like the publicly-owned bikes, emblazoned with the names of banks, that now line London’s streets. And those bikes mostly how such a plan would be a success: with ambitious marketing and coverage, the bikes quickly became an advert for shared, public, common methods of transportation, and a useful example to other cities planning to do the same.

A similar, private plan is more warning than caution. This year, a Singaporean company known as oBike attempted to launch a private plan for something rivalling TfL’s bikes, and looked to stand out with a dockless system that let anyone drop them anywhere, ready for the next person to pick them up.

But the launch was a disaster: the bikes were being thrown down in large numbers outside of Tube stations, in a phenomenon that came to be christened the “yellow bike plague”. Soon after they launched, London boroughs had to seize the bikes and take them off the streets.

Some blamed people, others blamed the company. But what was clear is that large rollouts of new methods of public transportation requires regulation and the clout to back it up – the kind of clout TfL is now flexing in its dispute with Uber. Autonomous vehicles are going to be more disruptive than apps that let you call taxis and pick up bikes; that might excite the tech execs and government ministers leading the charge, but there’s a reason the phrase “travel disruption” tends to be associated with leaves on the line and planned engineering works.

TfL’s dispute with Uber has also shown the enduring power of its brand. A YouGov poll taken soon after the ban was announced found that 43 per cent of Londoners surveyed agreed with the decision to revoke its license, with only 31 per cent disagreeing with it. Positivity towards Uber also dropped from mostly neutral to actively negative in the wake of the ban, according to different data from YouGov.

London might be well placed because it has TfL – it is unusual in having a transportation agency that people like. But it has other problems, including a road system that in many parts is pre-car, not to mention pre-self-driving car; the roads are so thin and the pavements so unclear that it’s likely to make it very difficult for autonomous vehicles to understand where they are.

That, of course, is not the layout of Silicon Valley, where the cars were born and continue to mostly be developed. There, as with much of the US, people drive more and along big, clearly marked highways – the cities are more ready for autonomous vehicles, which might account for why their inhabitants are so set on bringing them to their streets.

“American cities mostly being on a wide grid structure definitely makes autonomous vehicles more suitable there,” says Harris. “And they have a lot more existing segregation between roads and other things. In big cities in the UK, there’s a huge amount more mess and clutter.”

Part of the issue, for instance, is that in the UK cars and pedestrians come up against each other, walking just inches apart. It’s one that autonomous vehicles could solve; allowing them to drive around highways around the city, and giving over streets to pedestrians, would be a way of freeing up large swathes of public space. (Something like that is already happening in areas like Oxford Circus, which is set to become pedestrianised by the end of 2018, even without the influence of autonomous vehicles.)

“If you think about it from the perspective of what’s most efficient, having individual vehicles is not the best use of road space,” says Harris. “It’s walking, cycling, high capacity buses. Autonomous vehicles could change that equation, and I would be a shame if they swooped in as a way of replacing those high capacity ways of getting around, and of walking and cycling, which both have lots of extra benefits.”

But equally the problem of roads and their safety is one that autonomous vehicles could exacerbate, if not used properly. More cars means more of them on those already packed streets, which in turn could bring with it a whole host for people in both cars and outside of them. That is one of the major problems facing cities as autonomous vehicles arrive, and it’s one that could require radical redesign and replanning to actually address.

“This technology could be a way of solving lots of planning-related, town and city-related problems that we have,” says Harris. “You need to think of autonomous vehicles as one part of a much wider transport system rather than in isolation.”

It’s not just simply a question of redesigning the roads, but the entire map that fills in the spaces between. There’d be no need for city centre parking, for instance, since cars could just drive off somewhere else to wait – and so we could redevelop the space currently used for that, either into new housing or into something more ambitious like green space. Our cities could be entirely remapped to make way for new and revolutionary forms of travel, though as ever the simple question of where and how big roads are is likely to dominate the discussion.

As well as the design of cities, the threat of terrorism could undermine the introduction of autonomous vehicles, too. Self-driving cars are vulnerable to hacking, and if they are used to further the kind of attacks that human-operated vehicles have enabled, then the work to get them into cities is likely to be set back immediately.

“With millions of lines of software code, today’s connected cars offer malicious hackers numerous attack vectors,” said Alexa Manea, chief security officer at BlackBerry. “The impact of such a cyberattack could range from traffic congestion and inconvenience to life-threatening danger to drivers, passengers, pedestrians, and innocent bystanders. Developing an effective security framework to combat these threats is a challenging but necessary step towards making autonomous vehicles a reality.”

But as with much of the work on autonomous vehicles, responding to that threat is a benefit whether or not they actually turn up and take over our roads. Dividing pedestrian paths from streets of vehicles keeps people safe and makes cities happier – whether or not those vehicles are being driven by people or by computer chips.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks