Earth is making the Moon rust, scientists find

Scientists could not understand how oxygen was moving to the moon, but found it travels via magnetic field

Researchers have discovered that the moon is rusting, and Earth is partially responsible for causing it.

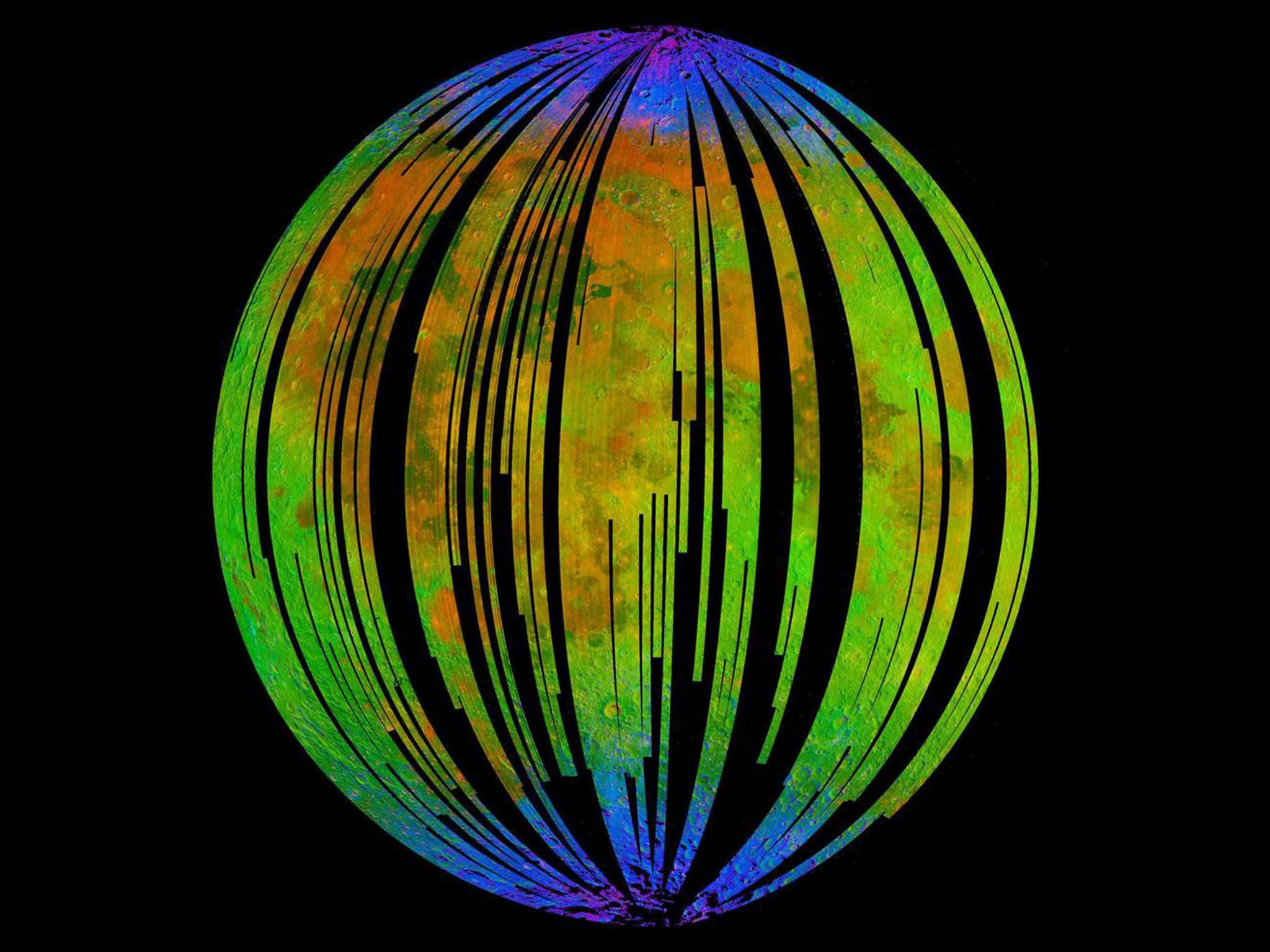

A new paper, studying data from the Indian Space Research Organisation's Chandrayaan-1 orbiter, reveals that the moon’s poles have a significantly different composition than the rest.

Studying the light reflected from the poles, the University of Hawaii’s Shuai Li found the spectral signature for hematite.

Hematite is a form of iron oxide, commonly known as rust; however, in order for iron to become rust oxygen must be present – something the moon is infamously lacking.

“It's very puzzling,” Li said in a statement. “The moon is a terrible environment for hematite to form in.”

To answer this question, Li contacted Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“At first, I totally didn't believe it. It shouldn't exist based on the conditions present on the moon,” Abigail Fraeman, one of the JPL scientists, said.

“But since we discovered water on the moon, people have been speculating that there could be a greater variety of minerals than we realise if that water had reacted with rocks.”

The presence of rust on the moon can be explained in three ways, the scientists discovered. Although the moon does not have an atmosphere, it does have trace amounts of oxygen present because of the Earth’s magnetic field.

Oxygen can travel from the planet to the moon by riding Earth’s magnetic field, making the 385,000 kilometre trip via the magnetotail.

This would explain why there is a greater amount of hematite on the side of the moon facing the Earth than on its far side.

It is also possible that more oxygen was transferred to the moon when it was closer to the Earth, as the two bodies have been moving further away from each other for billions of years.

Another cause is the amount of hydrogen present on the moon. Hydrogen bombards both the moon and the Earth, travelling across space via solar winds from the Sun.

Hydrogen is a reducer, which means it add electrons to the materials it comes in contact with, as opposed to an oxidiser which removes electrons.

The Earth’s magnetic field protects it from this, but the moon has no such protection.

However, the Earth’s magnetotail, as well as passing oxygen to the moon, also blocks nearly all of the solar wind activity whenever the moon is full. This means there is an opportunity for rust to form during the moon’s lunar cycle.

The third factor is the water ice that is present on the moon, found under lunar craters on the moon’s far side. Li has suggested that dust particles that regularly hit the moon could free these water molecules, mixing with iron and then becoming heated to increase the oxidisation rate.

This would explain why hematite was detected far from the moon’s craters, however, more research is needed to be done to fully explain how the water is interacting with rock.

Such research could help explain why hematite found on other airless bodies like asteroids.

“It could be that little bits of water and the impact of dust particles are allowing iron in these bodies to rust,” Fraeman said.

The research will be published in Science Advances.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks