Laser eye surgery: What it's like to see in focus for the very first time

There's a moment of intense pressure, rather than pain. The most disconcerting thing was the slight smell of singed flesh - but it was over in seconds, when I could finally say goodbye to glasses and contacts

A couple of weeks ago, I sat down on my sofa and watched the season five finale of Game of Thrones. Nothing heroic or unusual to brag about there – after all, tens of thousands of people did the same, to varying degrees of pleasure, shock and disbelief. Nevertheless, that hour-long episode was ground-breaking and unique for me alone, for I watched the bloodthirsty series climax for the first time in 26 years… with my very own eyes.

A week before, in a move not dissimilar to the brutal torture of a member of the noble Westerosi, I lay down on a bed while a surgeon taped my eyelashes to my eyelids, clamped my eyes open with a speculum so I couldn’t blink and then used a laser (the Ziemer LDV) to burn a thin flap in each of my corneas – the clear part at the front of the eye. He then lifted those flaps aside and used another laser (the WaveLight Allegretto Eye-Q 400Hz) to remove and shape the corneal tissue to correct my vision. Phew. I may just as well have chosen a crossbow.

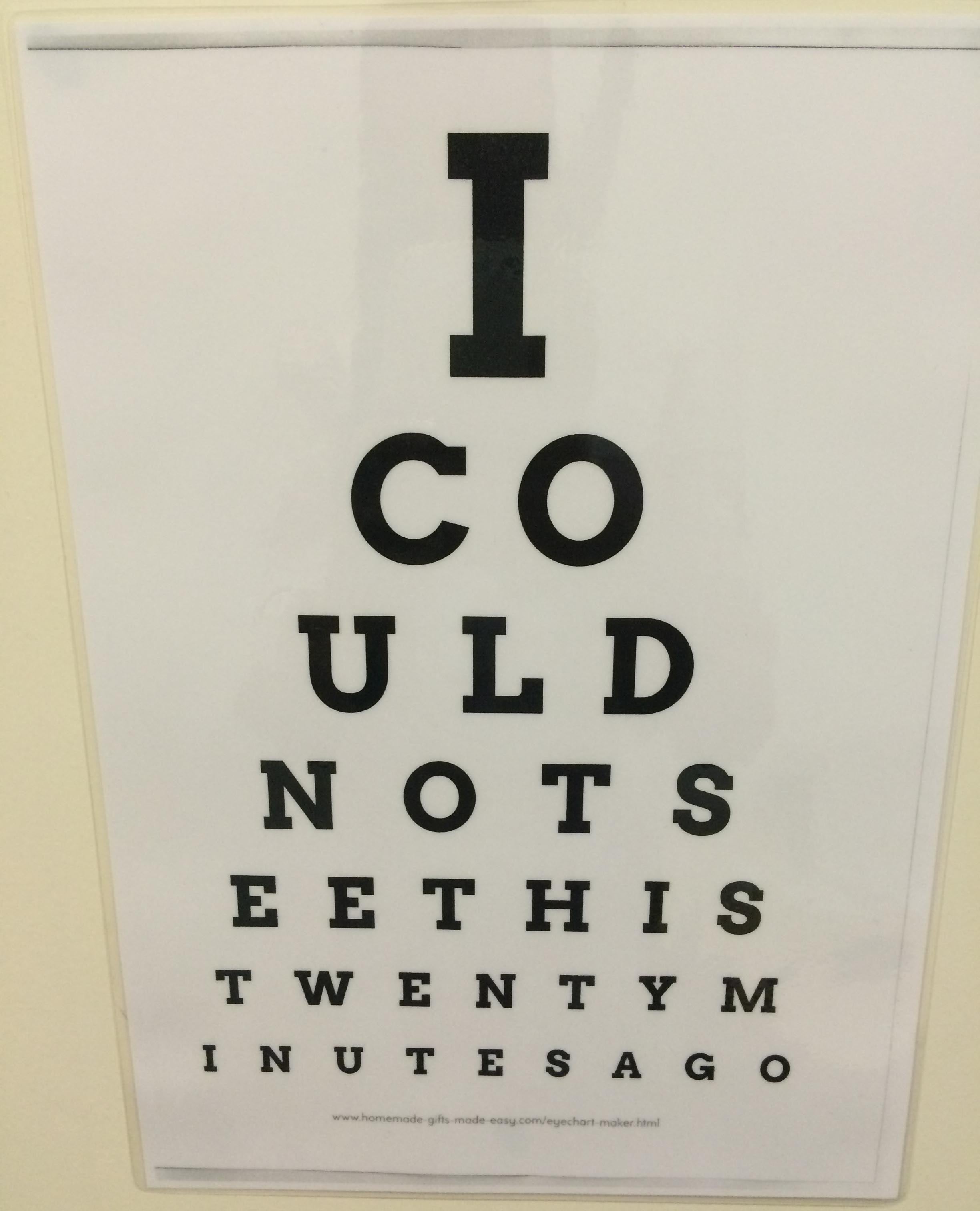

Horror aside, the promise of 20/20 vision in just 20 minutes (10 minutes per eye, more or less) with a reassuring 100 per cent success rate had me boldly tucking my hair away into an unflattering surgical cap, donning shoe covers, sheepishly grabbing two ‘stress balls’ to squeeze if it became too much to handle.

I was nervous, of course. Even the reminder that I have ‘given birth without any pain relief’ on my scoreboard of personal achievements didn’t help much, for there’s just something about the eyes, isn’t there? I spent years happily shoving in contact lenses with my fingers, with no qualms whatsoever. Yet I was more than a little squeamish at the prospect of having them permanently altered in the time it would take to cook a bowl of rice.

I was on the brink of turning around and saying I would stick to spectacles, thank you very much, before running away – were it not for the fact that in the last year or two, as I’ve spent longer staring at screens, my eyes have grown more sensitive, my tolerance to wearing contacts shorter, my reliance on glasses paramount. My eyes, compared to friends and family, weren’t even that bad: short-sighted with a reading of -3.75 in one, -3.50 the other, yet I longed to be able to swim without worrying about losing lenses in the water, and to not have to juggle two pairs of prescription sunglasses and normal frames on a bright sunny day. I wanted to be able to wake up without blindly scrabbling for my specs – and to stop worrying how I would ever cope in a middle-of-the-night fire.

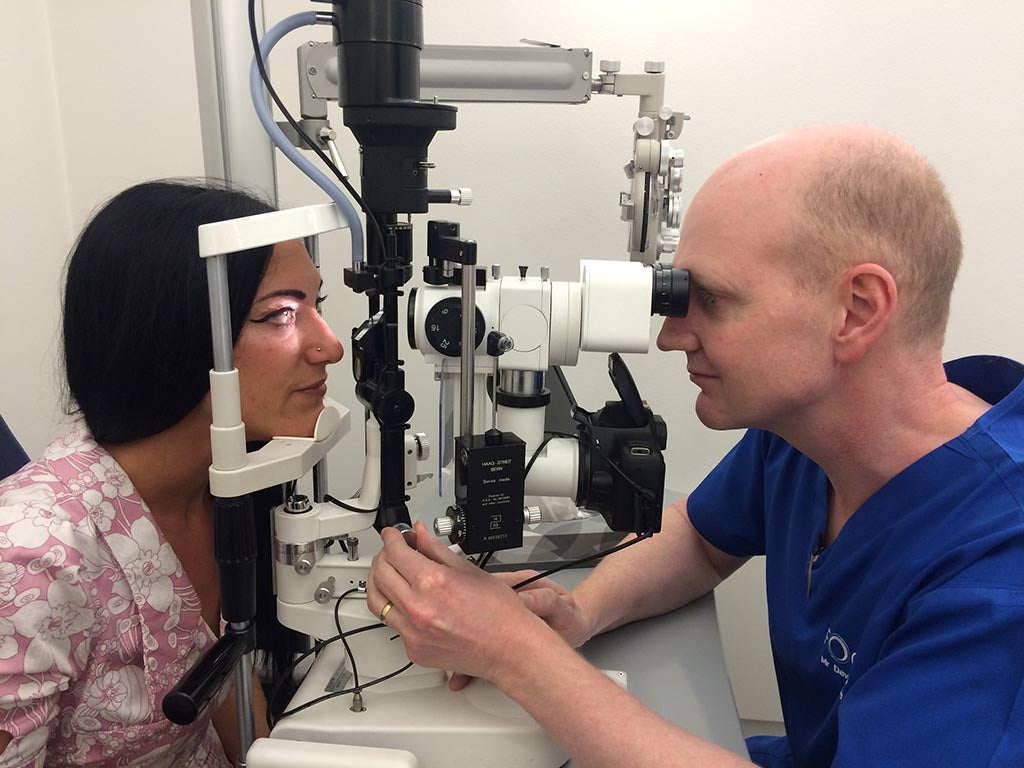

So, nothing ventured, nothing gained: I took a deep breath and looked up without blinking (I had no real choice) as Mr David Allamby at Focus Clinics (my decision on where to go came down to location, reputation and personal recommendation; though there are alternatives) put drops of anaesthetic in to numb the eye, before creating the flap. This was the most painful part, but only lasted as long as a 20-second countdown.

It felt like a moment of intense pressure, rather than pain; similar to the way it feels if you press your thumbs into your eyeballs until your vision goes blurry and you see stars. The reshaping of the cornea I couldn’t feel at all – the most disconcerting thing about it was the slight smell of singed flesh. But hey, everyone likes a BBQ, right?

Everything went black while the serious stuff was going on (thankfully only for a few seconds) and then the lights above me swum back into vision… in focus, for the very first time. Afterwards, Mr Allamby told me that he had in fact performed a total of 140 individual actions in just 10 minutes to help me to see properly. Afterwards, I was left only with a feeling of awe – and absolutely no pain. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t more nervous for the other eye, which he did straight after the first, because the 20 seconds of discomfort were real and unpleasant. But 20 seconds – what else can you do in 20 seconds, that wouldn’t make it worth it? You can’t even eat a chocolate bar in that tiny sliver of time, or make a cup of tea. 20 years of bad sight, wiped out in under a minute.

And so, unlike Jon Snow, I lived to tell the tale and now I (almost) can’t remember what it was like not being able to see properly first thing in the morning. The hardest part about it? Not being able to wear make-up for a week after having it done, and remembering to use my eye drops. Mr Allamby tells me that with age, long-sight is inevitable, as the lens of the eye hardens every year. It means that in ten years or so, I may well find myself wearing glasses again; but at least I’ll have the same amount of time to build up the nerve – and funds – to have that corrected, too.

Laser eye surgery Q&A

What is it?

Laser surgery, or laser refractive surgery, usually involves reshaping the cornea – the transparent layer covering the front of the eye. This is done using a type of laser known as an excimer laser.

What different types of laser eye surgery are there?

LASIK (laser in situ keratomileusis): the most common procedure in the UK. Long-sightedness and short-sightedness can both be corrected with LASIK, but it may not be suitable for correcting high prescriptions. Surgeons cut across the cornea and raise a flap of tissue. The exposed surface is then reshaped using the excimer laser, and the flap is replaced.

PRK (photorefractive keratectomy): mainly used for correcting low prescriptions. The cornea is reshaped by the excimer laser without a flap of tissue being cut.

LASEK (laser epithelial keratomileusis): similar to PRK but the surface layer (epithelium) of the cornea is retained as a flap. Retaining the epithelium is thought to prevent complications and speed up healing.

Wavefront-guided LASIK: tailor-made form of LASIK that reduces the natural irregularities of the eye as well as correcting eyesight.

What conditions can it treat?

Different techniques are used to correct short sight (myopia), long sight (hypermetropia) and astigmatism.

What do you need to be aware of before having it done?

You usually have to be aged 21 or over and your prescription should not have changed for at least two years.

Can I get it done on the NHS?

Laser refractive surgery is generally considered non-essential, so it's not usually available on the NHS.

Who should I get to do it?

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCO) recommends that doctors doing the surgery should be registered ophthalmologists and have additional specialist training in laser refractive surgery. For more information visit www.rcophth.ac.uk or read NICE information for the public.

Where should I go?

Research, research, research. Read testimonials, and talk to people who have had it done to see if there’s a clinic – or particular surgeon – they would recommend. Book in for a consultation to discuss treatment options and compare prices. Here are some of the most popular:

https://www.opticalexpress.co.uk

https://advancedvisioncare.co.uk

https://www.londonvisionclinic.com/

How much does it cost?

Prices vary according to your prescription, and the clinic you choose. Treatment can cost anywhere from £395 per eye for standard surgery to £4,600 for Z-Lasik specialist complete treatment for both eyes. Many clinics offer monthly payment plans. You’ll need to book a consultation to find what’s best for you.

What are the risks?

Complications occur in less than 5% of cases. Some people have a problem with dry eyes – artificial tears can help. Other patients experience glare or halo effects when driving at night in the weeks or months after treatment. In rare cases, too much thinning of the eye wall can make the shape of the eye unstable after treatment. Severe loss of vision is very rare.

How long will it take to recover?

Most people are back at work within a few days to a week.

For more information visit http://www.nhs.uk/Livewell/Eyehealth/Pages/Lasers.aspx

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks