Measles makes its mark all over again: One of humanity's oldest foes is back on the increase

As an outbreak in the US renews debate about this silent killer, Leigh Cowart puts the virus under the microscope

Abu Bakr Mohammad Ibn Zakariya al-Razi – the great Persian physician often described as the grandfather of pediatric medicine – was a meticulous man. Before the age of 30, he discovered ethanol, thanks to the careful application of the then new art of distillation.

It's not like that today, but the disease is no slouch either. In 2013, according to the World Health Organisation, there were 16 deaths from the virus each hour, around the world, for the entire year. It is one of the leading causes of death among young children, despite our ability to safely vaccinate against it. It is estimated that between the years of 2000 and 2013, vaccination has prevented 15.6 million deaths. Do you recognise it yet?

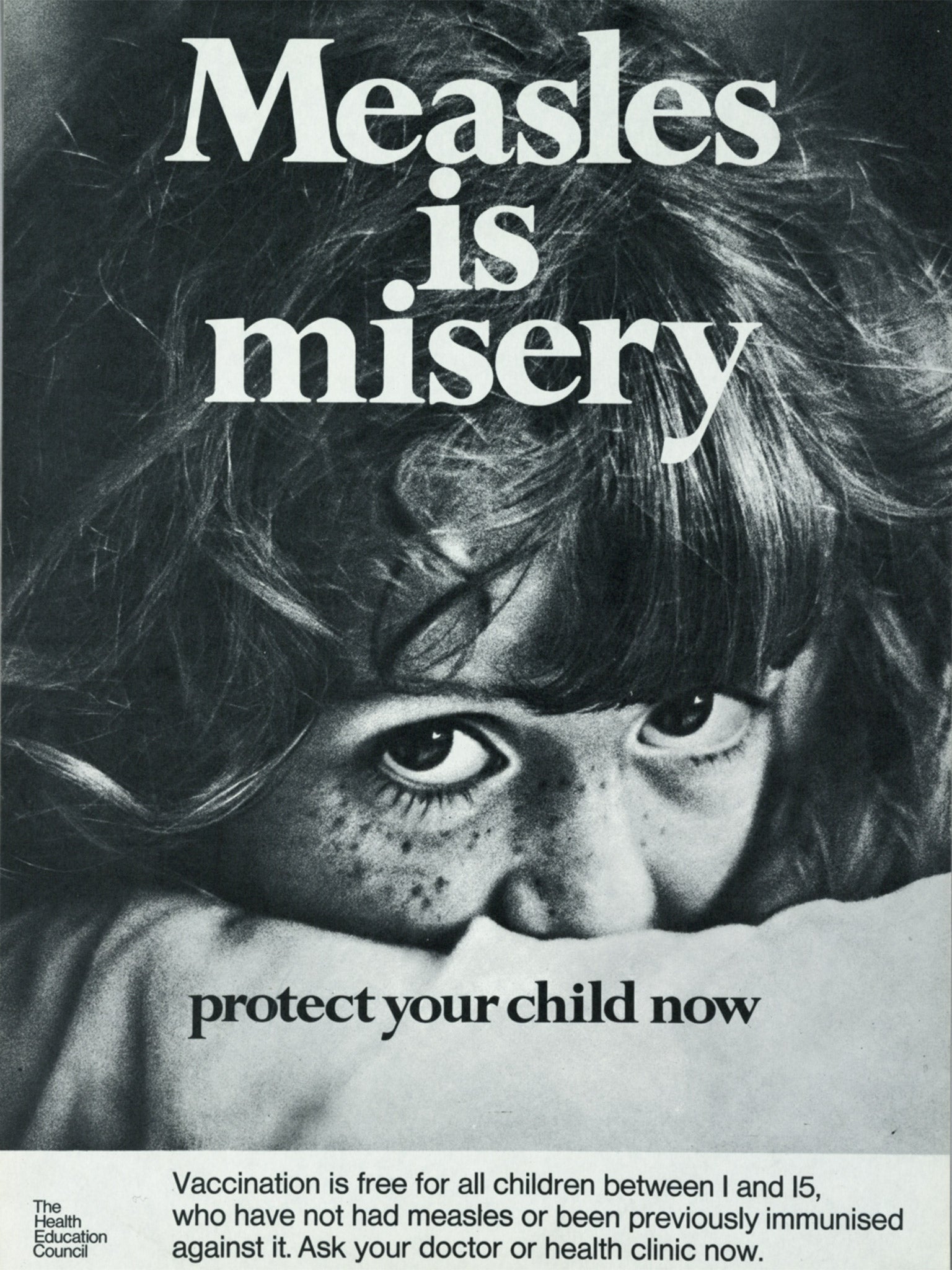

Everyone has, at some point, seen the picture of the measles child – that straw-haired toddler covered in head-to-toe tomato-red splotches. It's a photographic representation of abject misery: the poor child, betrayed by his immune system, with features blurred by a four-day rash. But while a picture of hundreds of unsightly lesions might be shocking, it's still not sufficient evidence for parents more afraid of the false spectre of Andrew Wakefield – author of the 1998 fraudulent research paper linking the MMR vaccine and autism – than the real-world danger of death by measles.

Despite the United States having declared measles eliminated in 2000, the virus has awoken anew, and with all the grace and predictability of a large bear coming out of sedation. Clusters of low vaccination rates are reviving this Lazarus virus of the West, with outbreaks springing up at a disconcerting clip. So, for anyone new to the disease, it's time to meet your measles.

After all, the measles already knows you.

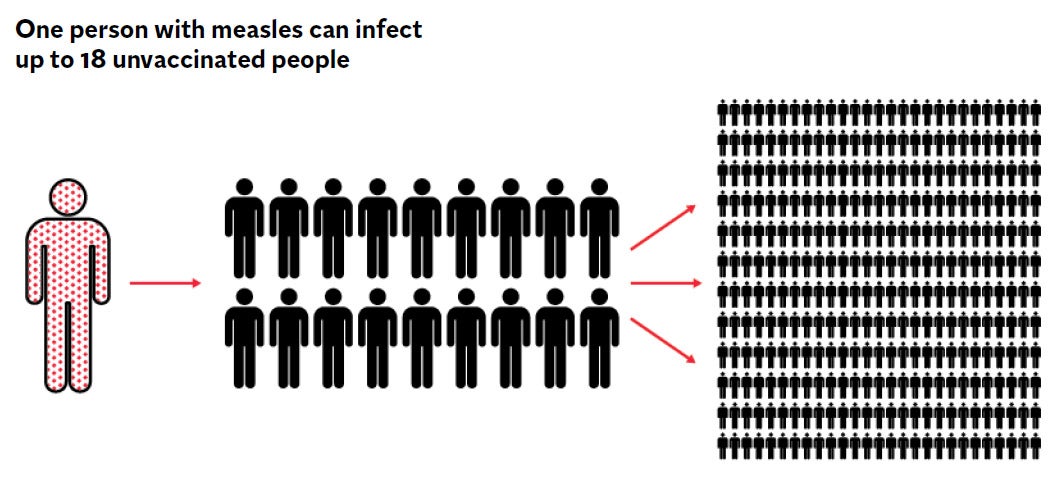

Though best known for its telltale dappled rash, measles is a wildly infectious upper respiratory disease. Like the flu, it's airborne – and successful. It has a near-perfect infection rate: Put your baby in a room with a measles patient, and nine times out of 10, measles is coming home with you. In the space shared between you and a coughing, sneezing measles-ridden sap, the sweet oxygenated room air and unavoidable door handles are thought to remain infectious for up to two hours. And measles delivers a double whammy because a person becomes infectious before they even know they have it. Four days prior to the rash is when most people become able to spread the love. Here's how the virus pulls it off.

So how do you know if you have measles? Symptoms start out like standard-issue wintertime gunk: fever, cough, runny nose, red eyes. A few days of that misery and the decorative stage of the illness starts with a carpet of red lesions. Koplik's spots may appear before the rash – that's when the bright, beefy red of the inner cheeks become studded with lots of tiny, blue-white dots. Complications from measles arise in almost one in three reported cases, and range from diarrhoea (8 per cent) and pneumonia (6 per cent) to encephalitis (0.1 per cent) and death (0.2 per cent). It gets worse.

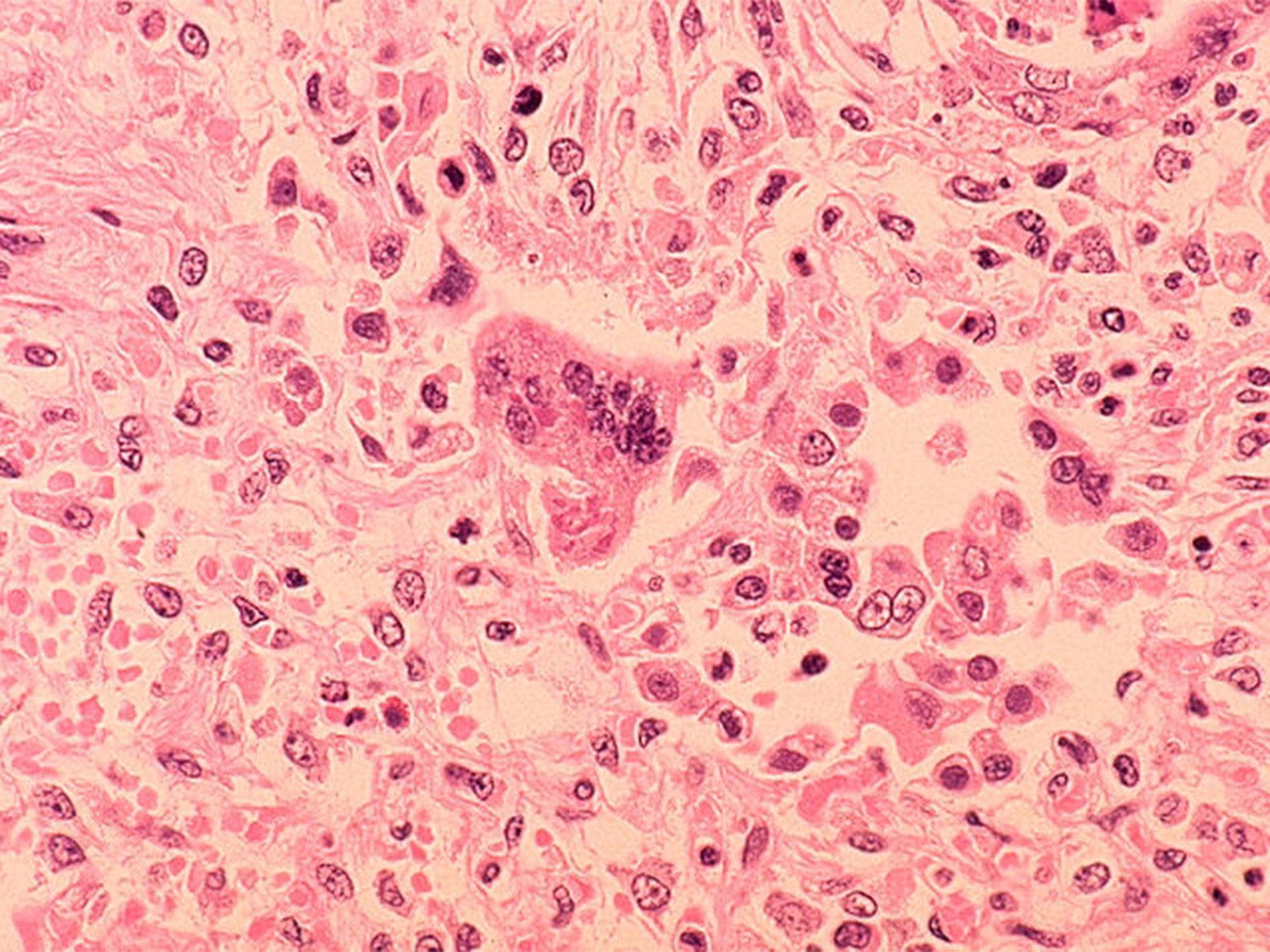

After coming in on the air like an old-school miasma, the measles virus jumps in through the upper respiratory tract or the eyes. However, before it can make a beeline for the closest lymph nodes, measles has to get inside the cell. To let you in on a secret, the entire field of molecular biology is basically just the study of the secret handshakes between tiny bits of stuff, and that's exactly what is happening here. The measles virus is encased in a membrane that has two different surface proteins: hemagglutinin (H), which is like a magic wizard lock picker, and fusion (F), which clearly has the better name.

The virus rolls on up to an epithelial cell and mashes its magical lock picker into a receptor site; slip it in the right place and it kicks off a molecular chain of events that wakes up the fusion protein. The fusion protein then blorps the virus into the cell. It's all very technical.

Once things get started, measles really gets around the body. Travelling from the lymph tissue near the site of infection, it hitchhikes over to some nearby lymph nodes and sets up shop for replication and destruction: part of this process involves a steep reduction in the body's available cache of certain types of infection-fighting white blood cells. Copies of the virus then hop into the bloodstream (viremia), and from there it's a one-way ticket to measles town. Measles in the skin, measles in the other lymph nodes, measles in the kidneys, measles in the gastrointestinal tract, even measles in the liver; that's in part because the virus can hijack the cellular replication machinery in lining of blood vessels and epithelial cells, as well as several types of infection-fighting cells. That's right: measles replicates inside the very cells tasked with its destruction.

It's macabre. That the virus is already jumping off to other people before the infected feels sick or notices a rash is one thing. That you can seem to have recovered from measles, only to die from it later, is quite another.

There are several ways measles can affect the brain and immune system on a longer timescale beyond a few sick days. For one, patients who clear the infection are left temporarily immunocompromised and open to new infections. "The link [between measles and post-infection immune suppression] is clear," Dr Diane Griffin explains. She's the chair of the department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health.

However, it's in the brain that measles really gets on the long game. In individuals who are immunocompromised before their altercation with measles, the virus can infect the brain, causing a fatal disease that progresses over the course of one to 12 months. This disease is called measles inclusion body encephalitis. Rarely, in some children and young adults, measles can cause a slowly progressive disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis. It's the result of a persistent infection that often ends fatally seven to 10 years later. "In addition, it can trigger an autoimmune demyelinating disease, post-infectious encephalomyelitis, soon after infection, that is frequently associated with neurologic deficits in those that survive," Griffin says. In plain English? This means that the measles can turn your body's militia against itself in such a way that it literally messes with your brain.

Until the mid-20th century, humans were at the mercy of measles. Pretty much every child got it, making it a childhood rite of passage, albeit a lingering and occasionally deadly one. If you were young prior to John Enders and Thomas Peebles discovering the vaccine in the 1950s, chances are you spent some of childhood covered in red splotches. But with the advent of vaccination programmes, humanity has been cracking down on measles – with some exceptions.

Ah, yes. The anti-vaccination movement. As public health agencies around the world are learning, perception is everything, and people have a hard time remembering dangers they cannot see. By successfully eradicating measles from society, organisations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and WHO created another problem: compliance. Big Pharma makes a much better villain than the invisible monsters your grandma yabbers about, and really, who dies from a rash? I mean, 145,700 people a year – and that's after the 75 per cent drop that happened between 2000 and 2013 – but who's counting?

But now, with parents opting out of childhood vaccinations – especially rich parents who can circumvent the public health system – measles is regaining its status. In California, where the latest outbreak started, there is a clear gap between the choices of the poorest and the most well-off.

What that means for the younger generations remains to be seen, but the future looks grim. We know that immunity gained from exposure to wild measles lasts at least 65 years, but what about the vaccine? "We do not know how long protective immunity lasts after the vaccine," says Dr Griffin. We know that 99 per cent of recipients of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine can be protected for more than 20 years after two doses of the jab, but beyond that? I suppose we're about to find out.

You can't really blame us for forgetting, though: it's an all too human reaction. After all, the saying "time heals all wounds" is just a nicer version of "don't worry, you'll forget how much this sucked". The troubles ahead are what happens when we forget the real danger and focus only on what we perceive to be the biggest threat. Disengaging from the vaccine system becomes a nice, passive way to feel like you're protecting yourself from "maybe" dangers. Suddenly, not vaccinating starts to look like caution. We've spent the past 100 years or so running around like public health mercenaries, isolating, defeating, and chaining up the monsters of old, but it seems that perhaps we've done the job too well. Would you wear a seat belt if car accidents stopped happening in the 1950s?

We are scared of the wrong bogeymen and have forgotten the monsters that lurk in the shadows of pre-schools. We've learnt to view these seasoned killers as easily defeated foes, not titans of mortality and morbidity. We treat them as pests. But these are not pests. These invisible monsters are coming back – measles, whooping cough, polio, scurvy. And they know us better than we know them.

So, if you find yourself with strange spots in your mouth, the glossy, wet pinks of your cheeks spotted with a field of white-blue dots, think "measles," not "X-Files STI". Stock up on supplies and batten down the hatches for a fun-filled romp through full-body viral rash and a head full of snot. And as you're blooming into a veritable rose garden of red rashes, be a dear and phone everyone you hung out with in the days before you realised you were a disgusting sick person. Because not only have you just met one of humanity's oldest foes; so, too, are your unvaccinated acquaintances about to meet their measles. Welcome to the revival of the sickest.

This article first appeared on Medium.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments