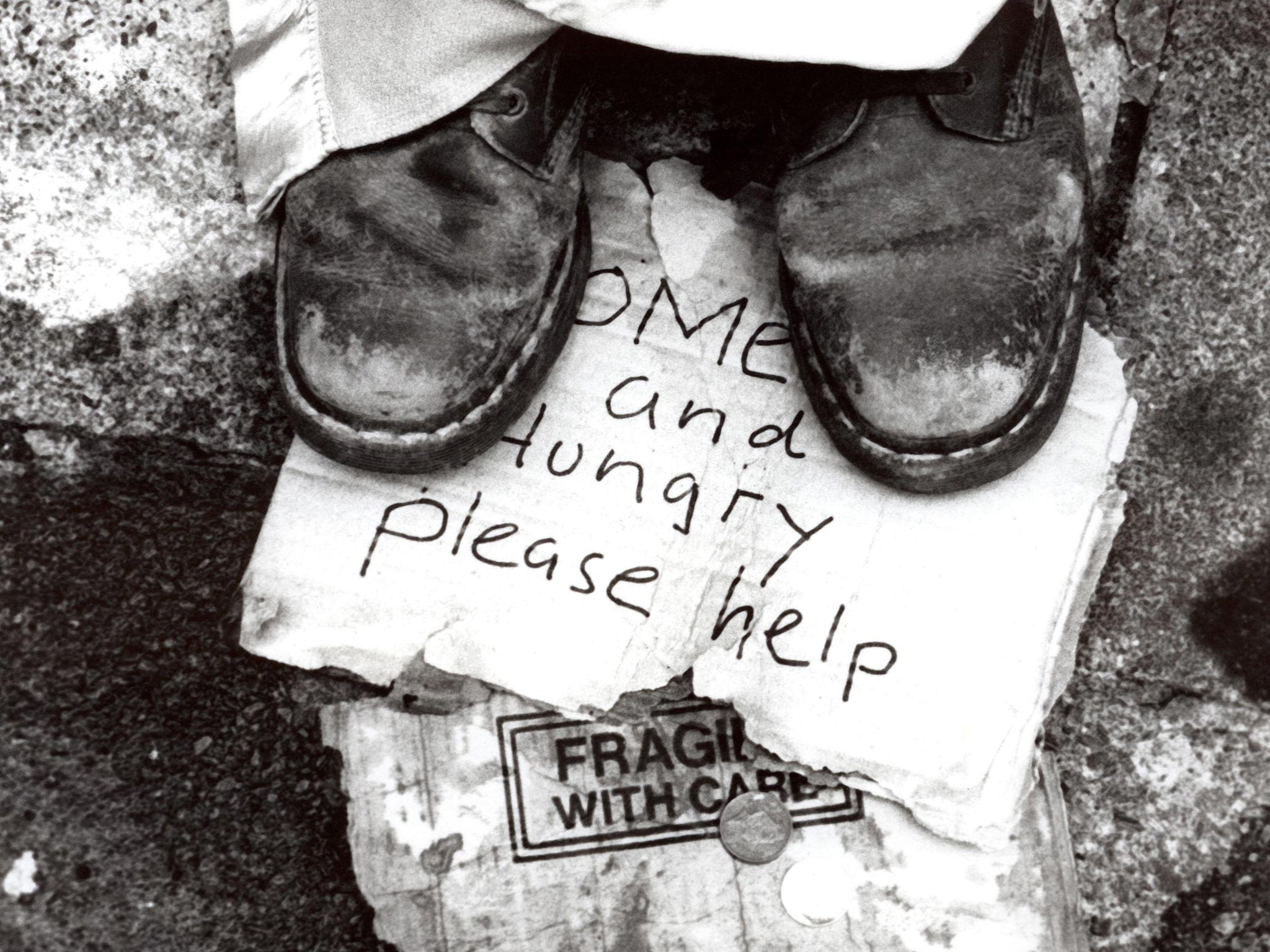

Out in the cold: A writer spends a night on the streets and hears the stories of the homeless

Rough sleepers - the homeless, the destitute and the drunk - exist in every city. Will Nicoll meets those whose luck has run out

Will Nicoll is a British writer and journalist, who has been shortlisted twice for the Shiva Naipaul Memorial Prize. This is an extract from a longer essay, which was published by 'The Los Angeles Review of Books'

Bristo Square is a vast Gothic courtyard outside Edinburgh University, adorned with dark granite gargoyles. It's night-time, and the thoroughfare between the buildings is busy. Three young women in stilettos and white suede cowboy hats, trimmed with pink fur, stumble past; unnoticed, street people criss-cross the revellers. Some are young refugees, care leavers or migrant workers; many are gnarled old rough sleepers, who carry their belongings in plastic bags. A few scream abuse at passing students, but most walk on, fearful and quiet, with their eyes fixed on the buildings ahead. All belong to a silent underclass who exist quietly and painfully in every city.

There are an estimated 1,700 rough sleepers in Scotland. Edinburgh, with more than 360, is their capital.

As the sun falls behind the mosque's turquoise dome, the street people make their way towards Magdalene House – a soup kitchen known by only the destitute. As I push open the heavy wooden door, with its weary hinges and reinforced glass panels, I smell tonic wine, lentil soup, and turpentine. It's being redecorated, and the pine panels on the walls have peeled, revealing craters of pastel-pink paint.

Inside, there are men with thick, dark beards and beetroot-red faces, and men who are jaundiced and yellow, with wide, bloodshot eyes and lank, thinning hair. There are atrophied soldiers – drunk on white spirit – and old sea captains, who wear their war wounds like ghost stories. Some scowl, or shudder, as they pick tobacco flakes from their gold-capped teeth; others flinch like mice caught near the tracks of a runaway freight train, as the night air fills the room.

"We used to get them, back when they were on the methylated spirits," a woman says, as she dispenses soup from behind the serving counter. She glances at me and smiles as she butters bread. "Now it's white cider. It's the same thing if you ask me."

I sit at a table beside John – a musician who has just returned to Scotland from America. He tells me about touring Europe with a band and about his psychiatrist in Massachusetts. Simon sits beside him. He is very young, and wears a torn polyester jacket, which is zipped to his chin. He stares past me, to a frieze of Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane, as he pulls apart Empire biscuits and arranges the glacé cherries in glossy patterns on his tray.

Archie is a recovering alcoholic in his late forties. He wears an immaculate pale blue shirt with a cutaway collar – donated by the Sue Ryder charity, he tells me, "but originally designed by Tom Ford". The table becomes quiet as he begins to talk about his drinking, and the incarceration that always followed.

"I didn't know about work," Archie says, through genuine bewilderment, rather than by way of excuse. "I thought that when you hit a certain age, you went and stood in the pub. You all just stood in the pub with your mates. And the very few times you weren't there, you were talking about what it was like being there. Or you were looking for a reason to go."

For a moment, Archie squares his broad shoulders and feigns aggression. John says nothing; Simon wheezes, as his eyelids close, and he inhales butane gas through the sleeve of his shirt. Slowly, his eyelids flutter, and his fingers begin to wriggle in the pockets of his coat.

"I never had a good start in life, going in and out of kiddies' homes," Archie continues. "In fact, I'll tell you this," he says, "I've seen a hell of a sight more violence in kiddies' homes than I ever have in prisons. And I've been on landings with lifers." Suddenly, he stands up, and his chair falls backward, screeching as it hits the floor. Addiction marks people with all the force of a hatchet, or a sculptor's chisel; it carves contours in haunted faces, and tears seams in weathered skin. The men who come to Magdalene House have little interest in food, or warmth or company. They are weary, tortured, ghosts of people – with bodies contorted by imperceptible pain.

When I walk across Edinburgh to meet Archie's friend Jack, work on the skyline has stalled. At the top of Leith Walk, they've torn down the tenements, and the abandoned diggers and cement mixers look other-worldly. A rusted wrecking ball swings like a bauble above a chasm in the city where a thousand people used to live and breathe.

Greenside Place is a stretch of grubby pavement in front of a quiet cinema complex beside one of central Edinburgh's busiest roundabouts. As I traipse up Leith Walk, my eyes grow used to the darkness – and I can make out the street people, who seem drawn like ragged moths to the light.

Jack is a gentle older man with shorn gray hair and intense blue eyes. He wears a pair of dark jeans and a red sweatshirt that says "Nebraska". He has a very soft Northern accent, an occasional stammer, and a tendency to apologise. His fingernails are broken, and there's a hard, white groove where he once wore a wedding band, pressed like twine into pork fat on his right hand.

At first, we say very little, but eventually Jack mutters, "Suppose you're sitting in a bedsit over there, and you're on your own, and you've only got a little TV. If you've got a hundred pounds in your pocket, and you go out on a Friday night, put a nice shirt on." He pauses. "Maybe put your hair up and put on a nice dress if you're a girl. If you go out clubbing then you're the same as the next man. You're a millionaire for a night."

Jack takes a plastic lighter from his pocket and taps it on the table.

"A lot of it's in the mind. Alcoholism is, because alcohol, if you only do it every now and again, it will lift you. Boom," he says, for emphasis, making the shape of gun in a gesture that feels unfortunate and sudden, and his eyes narrow. "But if you're doing it continuously, what alcohol will do is it will bring you up, and then it'll bring you right back down."

Jack hits his left palm off his right hand, and the resulting crack echoes like a gunshot.

"You won't get the up again because you're just on a continuous roll with it. That's the difference."

About half of the people who are passing through the British criminal justice system were drunk at the time of their offences. A slightly smaller group use alcohol in a way sufficiently chronic to be defined as a problem. Probation officers find that half their clients have a pattern of criminal behaviour associated with their drinking. Like Archie – and many of those who eat at Magdalene House – Jack is one of these men.

"I was in trouble through drink as a young man." He takes an old cigarette tin from his pocket and places it on the table. "I used to do TDAs, you know, taking and driving aways," he mumbles, referring to cars. "Then there was fraud. Cheque cards and cheques. I did a couple of sentences, in the old prison system. Anyway, I was in Strangeways, which is an old Victorian prison. One night, I got out over the hospital roof.

"Then I went abroad, and that was where my drinking began," Jack says, lighting the cigarette again. "My real drinking. I had an accident on a motorbike. I was in a wheelchair. Then I ended up in a hospital, suffering from a nervous breakdown and depression. I lost a house, I lost a job," he says, briskly. "I had a daughter in Holland who I've not seen from that day to this day. She's 22, nearly, now."

I can't help but wonder about the role that alcohol played in the circumstances; but Jack's eyes are clear, loving, and strangely mournful, like those of a man who'd sooner skirt the truth than tell a lie.

Suddenly, without warning, Jack mentions the night of his arrest in Suffolk for the first time, for the armed robbery of a petrol station.

"It was mad. I was pissed," he shrugs. "Every time, every crime, I've been pissed. When they were doing the reports on me, the barrister was saying, 'If that report gets done the wrong way then you'll get 12 years.' But the report was very good. The judge took a bit of lenience on me. He give me nine years." Jack counts aloud. "He give me four, four, and one."

"But that isn't very lenient," I say.

"If you've had the life I've had, then nine years in jail is more than lenient. Jail isn't a nice place. But it's food to eat, when you need it. It's a place to sleep – a place to keep your stuff. The guards treat you fine once they know you're not there to thump anyone, or cause them any hassle, or lie. Liars just don't last long in prison, because no one has any time for that. Jail has a funny way of making liars into honest people."

Jack seems to contemplate this for a moment. "It's only when they leave that they are taught how to lie again."

We begin making our way back toward the Salvation Army, where Jack is staying. We cut down toward Waverley Station and through the dingy, neon-lit arches. By a conservative estimate, half of those who sleep here are prison leavers. As many as 80 per cent will have a problem with alcohol or drugs.

"I'm no longer allowed to carry a nail gun. I can't use anything that fires a projectile," Jack explains. He's grinning. As part of his application to receive welfare payments, the Job Centre has insisted he begin a basic safety qualification to work in the building trade. Building sites are dangerous places, and nobody is going to employ him.

I want to ask Jack about that night in Suffolk, but I don't. I'm not looking properly as we walk along Calton Road, and a car swerves toward us.

"Watch yourself, son," Jack says, firmly and gently, as he takes my arm. "Watch yourself now."

On the loud, dank passageway known as the Pleasance, which marks the periphery of Edinburgh's Old Town, Jack introduces me to two men who stand outside the hostel, smoking. Buddha doesn't speak, but shoots surly, outraged glances at passersby and spits furiously on the street. Michael scowls angrily at the traffic, and brushes the patterns shaved into his eyebrows with thin, white fingers, like a child's.

Slowly, Michael describes leaving Birmingham because both of his parents were addicted to crack cocaine, and I realise that he's only 19. When Buddha eventually speaks, with shyness rather than hostility, it becomes clear that he has a learning disability that is very marked.

"I've got three places I can live," he says, slowly and precisely. "One room at my father's house, and one at my old lady's – but it's less lonely here. And you can smoke in your room, too," he shrugs. "They'd never let me do that at home." Later in our conversation, Buddha mentions that he is 32.

The manager of the Salvation Army explains, over reheated bolognese in a strip-lit, Formica dining hall, that 90 per cent of the current residents will have had contact with Britain's care system.

As he piles spaghetti on to his fork – in words thick with bitterness – he mentions how the majority will have been to prison, too. Many will use drugs, and most will drink excessively; despite constant contact with institutions of state, throughout their lives, charity is now their only support.

As I leave Jack, I find myself wondering about that night in Suffolk, why he had a gun, where he bought it, and what possessed him to rob a petrol station. He wasn't a violent criminal but a petty crook, and he knew enough from prison to realise that he would be caught immediately.

Alcohol gives us the illusion of power, when really we're at our most powerless. I imagine the taste of the whisky in my mouth, and that gun in my hand, no heavier than a bag of sugar.

Evoking the language of the Old Testament, Alcoholics Anonymous describes people such as Jack – and those who eat at Magdalene House – as the subjects of King Alcohol. They are dependent drinkers, beset by terror, frustration, bewilderment and despair, whose lives will end in jails or institutions – the shivering denizens of his mad realm.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments