Tattoos: Marked for life?

Around 20 million people in Britain have tattoos – and many of them suffer agonising regret. Nick Duerden visits a charity that can erase the pain

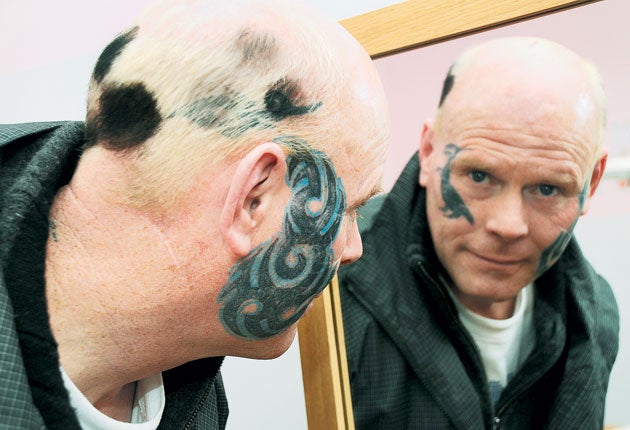

Six years ago, George Hallway, an out-of-work man from Sunderland, was out on the town. A long-term sufferer of anxiety and depression, he had been drinking heavily when he decided, on a whim, to get a tattoo, possibly two."I wasn't thinking straight," he notes now. This is an understatement.

He emerged from the tattoo parlour several hours later, his entire face transformed. A dolphin was now suspended in mid-swim high on his left cheek, a swirl of exotic tribal markings covering most of his right. He staggered home, numb, and woke the morning after with the realisation that he had ruined his life.

"I was devastated," he says, adding that he could no longer contemplate looking for employment, and found it difficult even leaving the house. "People would stop and stare at me in the street; small kids would be scared. I couldn't walk out with my head held high. It was the most stupid thing I've ever done."

Hallway, now 41, went to his GP to see about having the tattoos removed, but this service – which costs about £80 per inch – was no longer performed on the NHS and Hallway was in no position to go private. For five years, his problems spiralled – compounded, he believed, by his facial art – until he heard about the Human Life Trust, a charity that works to help people in his situation.

"There are approximately 20 million people with tattoos in this country," says Barry Crake, a micro- pigmentation technician who set up the charity last year. "And I'd suggest at least 15 million regret having them."

Tattoos, he argues, are not always merely fashion accessories, but what many people turn to when they don't have the courage to self- harm: "It's just another way of marking yourself," he says, revealing an arm and much of his chest covered in ornate green ink. "I should know; I've been there."

Crake, 39, and also from Sunderland, is a former self-harmer, dealing with what he describes as a "tough childhood" by burning himself with cigarettes. He was bullied at school, then later at work, but managed to turn his life around and felt compelled to help people in similar situations. Four years ago, after ditching his job as a mobile-phone salesman, he learnt the art of tattoo removal and worked privately until the NHS made its cutbacks, which he believes had a profound effect for those doomed to suffer for ever, "after one reckless moment of madness".

He now divides his time between private and charity work, and is so busy with the latter in his Sunderland office – people come to him from all over the country – that he has recently opened a branch in Chiswick, west London, to help cope with the demand.

"When people come to the charity wanting a tattoo removed we refer them first to their GP for a professional opinion," he explains. "If it is decided that removal will aid psychological improvement, will help their chances of rehabilitation [he works with many former offenders], and even finding work, then we go ahead and remove it."

The psychological ramifications of having a tattoo should not be overlooked, he says, for the simple reason that so many people now have them. Where once they were mainly the preserve of sailors and prisoners, they have become part of mainstream culture, a trend perhaps prompted, and certainly perpetuated, by popstars and premiership football players. But while camouflaged arms and lattice-work necks may go down well at Stamford Bridge, they translate less well in the real world. When Cheryl Cole had her hand tattooed a few years back, it prompted thousands of copycats.

"Your boss may have turned a blind eye to it at first," Crake suggests, "but he or she doesn't anymore." Many employers, including big banks, building societies and energy companies, operate a strict "no tattoo" rule. "And if you can't cover them up, you lose your job."

He spends much of his working day helping people who perhaps failed to understand just how permanent permanent ink can be, but he also helps those in far more distressing situations. "There is a certain kind of man," he says, "that likes to brand, or tag, his girlfriends. They either hold them down or, worse, knock them unconscious, and mark them with Indian ink – between their legs, their breasts, their buttocks. It's horrific, but it's a lot more common than you would think. These are the really upsetting cases, but they are also why we set up the charity in the first place – to help people who, through no fault of their own, would otherwise have to go through life marked forever."

Because of the high cost of the work, which he currently shoulders through his private work, Crake is looking for funding from either the Government or private investors. "It is expensive, but so worthwhile," he says. "And the difference it makes to people's lives is just amazing."

George Hallway is now a quarter of the way through his two-year treatment. Once a month he visits the Sunderland branch for another course of cream, called E-Raze, which is implanted under the skin and reacts with the ink, causing the area to scab over. With the scab's removal comes the first layer of the offending ink. More lies beneath. It is a slow, deliberate process.

Does it hurt? Hallway says: "A little, yes, but it's worth it. My tattoos are definitely beginning to fade, and I get a buzz from that. With them gone, I might just be able to get my life back. That's all I really want."

www.humanlifetrust.org.uk

How tattoos are removed

Laser

Laser treatment is the most common removal method. Ink particles are broken up by the laser and eventually cleared away by the immune system. Extended treatment can cause painful blisters and scabs (though this varies from case to case) and will cost around £50 to £300 per session. Large and multicoloured tattoos can cost thousands of pounds to remove.

Intense Pulsed Light Therapy

Similar to laser removal, IPL uses pulses of light rather than concentrated light to treat tattooed areas. It is less painful than laser removal and arguably more effective, but can cost a good deal more, averaging £50 to £200 per session (more sessions are required).

Surgical Methods

Cheap but brutal (from £100), these include dermabrasion, where the skin is eroded using sand (this is becoming less common) and excision,with the tattoo being cut away and the skin sewn back together. Used when laser removal is not an option.

Creams

Creams such as E-Raze and Lazer Cream are claimed to remove most tattoos within 3 to12 months. Effects will vary according to the size of the tattoo. It takes time, but is relatively inexpensive (£50-£180).

Fading with Saline

A less reliable method is saline fading, where an artist reapplies a saline solution to a tattoo to fade it, perhaps to reapply another tattoo. This is a controversial subject among tattoo artists, and is thus far unproven as an effective method.

Tom Duthie

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks