What's wrong with hypochondriacs?

We may mock them, but their terror of death and sickness can be a debilitating condition in itself. Brian Dillon unravels the tortuous connections between real and imagined illness through the lives of some of the afflicted

Hypochondria is an ancient name for a malady that is always distressingly novel and varied. In anatomical terms the hypochondrium is the portion of the body just below the ribs; in classical medicine, "hypochondria" was a general term for diseases (mostly of the digestion) that troubled that region. But the illness gradually lost its organic meaning and came to denote a purely psychological state. When we use the term today – generally with pejorative intent – it's to describe a tenacious fear of illness, or the mistaken conviction that one is unwell. Hypochondria, for patient and physician alike, is the shadow – often as troubling or frustrating – of real disease.

Why should some of us so misread the messages we receive from our bodies, or inflate in our minds the real health risks we face, that we become debilitated by fear and delusion? Why, when presented with strong evidence to the contrary, do hypochondriacs persist with their concerns, fretfully returning to the same symptoms or embellishing their bodies with new imaginary horrors?

Historically, the illness – for it was, and still is, a disorder in itself – was obscurely related to other popular diagnoses such as hysteria, melancholia and neurasthenia. In the wake of Freud, however, hypochondria seemed merely to mask more deeply-seated neuroses. But a diagnosis of "hypochondriasis" or (in its more contemporary variant) "health anxiety" is once again a common one, and this venerable distemper is now thought to exist on a continuum with other modes of modern worry such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder.

We can begin to discern the tremulous profile of the modern hypochondriac in medical treatises of the 17th century. For Robert Burton, whose Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) is a colourful compendium of mental and physical ailments, the symptoms of "windy hypochondriacal melancholy" included stomach pain, flatulence, cold sweats, tinnitus and vertigo; accompanied by fear, sorrow and delusions. But the precise cause eluded Burton, and it was not until the early 18th century that writers such as Richard Blackmore began to point to "a tender and delicate constitution of the nervous system" as a likely origin.

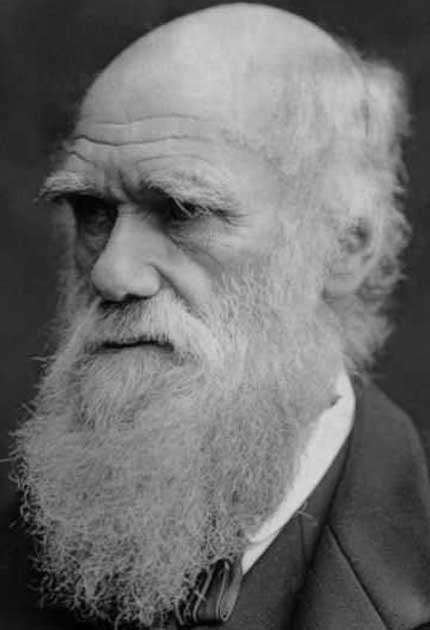

For the Victorians, the disease combined fear, misery and an organic disorder that arose, as it had for the Greeks, from the stomach. Among the more common treatments for hypochondria was hydrotherapy, the water cure that involved drenching the patient daily to bring about a crisis or turning-point. Dr James Manby Gully, prime exponent of the treatment in Malvern, proudly advertised his success in banishing "the fiend of hypochondria". Charles Darwin is Gully's most prominent patient, but many Victorian notables had recourse to the same cure.

Among the oddities of hypochondria's history is the fact that it has been thought primarily to afflict men. So entrenched was this idea in the 18th century that it was possible to call the stomach "the male womb": the origin of the disease, just as the uterus was said to be in cases of hysteria. By the mid-19th century, women such as Charlotte Brontë could also self-diagnose a disease that in its symptoms was perhaps close to what we would today call depression.

It's a phenomenon well known to Florence Nightingale, whose polemical treatise Cassandra is an obvious precursor to Virginia Woolf's better-known essay, A Room of One's Own. Nightingale inveighs against the constraints under which women live; expected always to be engaged in social or domestic activities, their only sanctuary is the sickbed, physical illness the only excuse for not fulfilling wifely or daughterly duty.

Nightingale did not think of herself as a hypochondriac, but in her bedridden industry she resembles a writer well informed about current medical theories regarding hypochondria at the end of the 19th century. Marcel Proust's father was a leading figure in medical hygiene and lectured on epidemiology, neurology and neurasthenia. His son was aware of the psychological origins conjectured for those disorders, and probably knew the theory of the "common sense" – the sense that sensed the other senses at work – supposed to have gone awry in hypochondria.

This latter theory – that hypochondriacs are too well attuned to bodily sensation and mistake normal feelings for morbid ones – was overtaken by Freud's conviction that hypochondria masked another neurosis: melancholia, narcissism, even homosexuality. Hypochondria ceased to be an attractive diagnosis and pointed instead to culpable repression. In famous cases such as the pianist Glenn Gould or Andy Warhol, the problem seems to be a reluctance to engage with the real world.

In recent decades, that fear has been characterised as an anxiety disorder: a pattern of would-be controlling responses (just like OCD) that can be broken with cognitive-behavioural therapy. But whether or not we have found the definitive cure for hypochondria, the history of the disease suggests that the fundamental doubts it raises – about what it means to be ill, or well, or just to be human – will not easily be assuaged.

'Tormented Hope: Nine Hypochondriac Lives' by Brian Dillon (Penguin, £18.99). To order this book for the special price of £17.09, with free P&P, go to Independentbooksdirect.co.uk or phone 0870 0798897. The author will chair a discussion of the medical and cultural history of health anxiety at Tate Britain on 18 September. Tickets: tate.org.uk, 020 7887 8888

Andy Warhol: Artist

Warhol had been a sickly child: he contracted rheumatic fever at the age of eight, and developed St Vitus's Dance, a disease of the nervous system that required weeks of bed rest. In adolescence, he was tormented by acne, and as a young man, he despaired when he began to lose his hair. Warhol divided the world into bad bodies and good, and spent much of his adult life trying to acquire a better body. After his shooting in 1968, he became morbidly afraid of hospitals: a fear that ultimately contributed to his death at the age of 58 in 1987.

Charlotte Bronte: Author

Brontë claimed to have suffered a fit of hypochondria while teaching at Roe Head, Mirfield, West Yorkshire, aged 19. She fell into "a most dreadful doom", which she believed had little to do with the sickly and doomed family milieu in which she lived. Rather, Brontë meant by "hypochondria" a dismal combination of sorrow, worry and resignation that arose, so she thought, from the fact that she now had no time to write or to think. Later, in 'Jane Eyre', she had Rochester accuse Jane of hypochondria when she expressed her fears about their planned wedding. In real life Brontë outlived her five siblings.

James Boswell: Writer

In 1763, at the age of 23, James Boswell suffered his first bout of hypochondria while studying in Holland. Arriving in Utrecht, he suddenly found himself plunged into worry, lassitude and depression. Boswell followed medical convention in attributing his anxious torpor to a rich diet and lack of exercise; among the remedies he tried were early rising, vigorous exercise, regular dining hours and moderate but healthy sexual activity. Decades later, in 'The London Magazine', he wrote more than 70 articles in the persona of "The Hypochondriack"; writing, he claimed, was the only cure he had found for his hypochondria.

Marcel Proust: Author and critic

The eccentric details of Proust's domestic life are well known: in particular, his oversensitivity to noise, which led him to line his bedroom at 102 Boulevard Haussmann with cork. But Proust then developed, or so he thought, an allergic reaction to the cork itself: his sensitivities were many and the precautions he took in their name almost as ruinous to his well-being as the asthma that wracked him from childhood. Damp towels, recently dry-cleaned gloves, new handkerchiefs and central heating; all of these and more he thought injurious to his person – while at the same time brilliantly satirising the hypochondria of others in his novel.

Florence Nightingale: Nurse and writer

On her return from the Crimean war, Florence Nightingale fell seriously ill with a vague set of symptoms that would plague her for decades. She suffered from insomnia, headaches, palpitations, breathing difficulties, back pain and loss of appetite. But through it all she carried on working, and her illness (real or imaginary) seems to have been a useful adjunct to her campaigning persona. As Lytton Strachey surmised in "Eminent Victorians" in 1918, Nightingale "found the machinery of illness scarcely less effective as a barrier against the eyes of men than the ceremonial of a great palace".

Charles Darwin: Naturalist

Darwin claimed that it was illness that had allowed him to work so hard and achieve so much; sickness kept the world at bay and required a rigid routine of rest and recuperation. The precise nature of Darwin's illness is unclear; he suffered from palpitations, gastric upsets, headaches and generalised feelings of being "dull", "old", "spiritless" and "stupid". Darwin may have been suffering from a disease acquired on the expedition of the Beagle (possibly Chagas's disease) but in his enthusiasm for the water cure and the professional uses to which he put his indisposition, Darwin seems his century's most-accomplished hypochondriac.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks