When we stop children taking risks, do we stunt their emotional growth?

Playgrounds are closing down. Parents rarely let their kids out of sight. Society is hamstrung by ‘health and safety', says Susie Mesure

A small face looms out of the gloom, bringing his red scooter to a halt just before the road. The boy, five, is on his own. Seconds later, he's off again, calling over his shoulder, 'I'll meet you after the bike tunnel.' I find him, breathing heavily, by the school gate, beaming with pride not at beating me but making the journey (more or less) alone. But his bubble is soon pricked: his face crumples after a classmate calls his exploits 'naughty'. And heaven knows what his grandma would say!

For parents, this is the dilemma of everyday life in the urban jungle: do we keep our children on a metaphorical umbilical cord or cut them free? It's little wonder that kids are growing up afraid to take risks when we're so scared of letting them live for themselves. And admit it, if you're a parent, you are scared, your heart beating a little faster at every headline of woe or tree they climb. Even, or perhaps especially, when we're paying someone else to look after them. Thus a working mum grabbing lunch in a café calls to check up on her child. First eavesdropped question, "Is the playground nice?" Then, "Is it soft underneath?"

We like our playgrounds cushioned and our children accounted for: they're signed up to music lessons, drama classes and organised sports as soon as they can walk and talk – the latest being mini rugby clubs for tots as young as two. "The dominant parental norm is that being a good parent is being a controlling parent," says Tim Gill, author of No Fear, which critiques our risk-averse society. But at what cost? And what's the alternative? And most importantly, when are we letting them play?

A Danish conference hall gently buzzes with grown men and women trying to replicate the exact pattern of six coloured plastic bricks being held up on stage. About 150 people have gathered in Billund, Lego's HQ, at the invitation of the brickmaker's philanthropic arm, the Lego Foundation, because they are worried that children are being short-changed when it comes to that "p" word, the right to which is enshrined in a UN declaration no less. They range from Harvard professors to ambitious entrepreneurs; all are united in their concern that children are paying the price for our parental panicking. In other words, playtime is over.

The upshot, warns Peter Gray, a psychologist at Boston College and author of Free to Learn, is anxiety and depression; even suicide is increasing. And it's all because children feel "their sense of control over their lives has decreased". He should know: now 70, he recalls growing up in the US in the 1950s. "By the time I was five, I could go anywhere in town on my bike. I could go out of town as long as I was with my six-year-old friend." His research links the rise of emotional and social disorders with the decline of play: "If we deprive children of play they can't learn how to negotiate, control their own lives, see things from others' points of view, and compromise. Play is the place where children learn they are not the centre of the universe." And in case you're not sure: "When there's an adult there directing things, that is not play."

David Whitebread, a psychologist at the University of Cambridge, tells one session how kids deprived of playtime can't learn how to "self-regulate", a fancy term for being able to control their own emotions and behaviour. This, he says, is so important for children's development that the Government's obsession with getting them to read and write ever younger is a "complete waste of taxpayers' money". His message is simple: "The big job is to teach parents that they must spend time doing things playfully with their children if they want them to do well. Self-regulation is a better predictor for how well children do later in life than reading and writing."

Back home, it's the Easter holidays and I need to put what I've heard into practice. But we live in busy south-east London, two-way traffic tears down our terraced street. I can't just tip my sons, aged five and two, outside. For starters, I'd probably be reported to Social Services: one recent Saturday, the postman came running up to our door because he'd seen both children set off down the street by themselves. For the record, they were walking approximately 100 metres round the corner to their friends' house. Our back garden is small, we lack nearby woods, and even the local park is a write-off: one tiny playground for under-fours too boring even for the two-year-old and the other, for over-eights, to be found padlocked and out of bounds.

It's a far cry from the open-to-all climbing frame outside Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum that we visited on a family holiday, and which required real ingenuity; or even its ambitious French counterpart, in the Marais neighbourhood of Paris, which replaced a far tamer version. No, our only real option was a Tube trip to the newly opened Tumbling Bay play area in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park – along with the rest of southern England as it turned out. This is the future of British playgrounds, or would be if councils had any money to build and maintain them: spending by English local authorities on public play areas fell by nearly 40 per cent from 2010 to 2013 according to a recent report in Children and Young People Now, an industry publication. As a result, almost one in three councils has closed at least one play facility. The Association of Play Industries (API), the manufacturers' trade body, last month said first- quarter orders for play equipment had sunk to an eight-year low. This followed the Government axing Labour's £235m Playbuilder programme to invest in play provision.

"Crikey! Crikey Heeeellllllpppp!" squeals an excited Louis, my five year old. He's disappeared up a haphazard wooden structure that reminds me of Enid Blyton's Magic Faraway Tree and him of a giant space ship. "Mummy! Look at my feet. They're not touching where they're supposed to. May," he barks to his friend. "Don't go the high way!" Too late: "I'm doing it Lou! I'm done. I'm done." Even the two-year-old is happy enough, roaming around in the bark chips being a troll underneath one of the bridges. For him, even the extra wide slide is a massive leap of faith when you're hanging, fingertips gripping the edge, willing yourself to let go.

Not that everyone is equally free to let themselves go: two boys wearing Spiderman crash helmets suggest not all parents are comfortable with what is undeniably a challenge. Which is as it should be, says John O'Driscoll, whose company Adventure Playground Engineers built the structure to an Erect Architecture design. He much prefers his play areas to look risky. "If you put up some steel poles, little climbing frames, and rubber surfaces, people think that's safe, so if an accident happens they're shocked. If you make something look risky, dodgy, hard and crunchy people make their own minds up. [But] breaking the odd bone is par for the course. Kids learn really quickly not to do something again. We're really fortunate to have the NHS. There's no need to sue anybody to get a broken arm fixed."

Ah, the so-called compensation culture. "We're trying to put adventurous play into public parks and schools but we're battling against a 'sue, sue, sue' mentality," O'Driscoll adds. "Some kids are growing up in nurseries with bouncy floors, growing up without the concept of gravel or grass. Everything they've played on bounces, which gives them a false sense of security," he says. Although statistics on playground accidents are impossible to find – the then k Department of Trade and Industry used to break down hospitals' A&E admissions but stopped in 2002 – experts are ambivalent about those rubber floors. "Has it been worth all those hundreds of millions of pounds?" asks David Yearly, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents' play safety manager. Impact-absorbing surfaces, as they're known, typically take between 30 and 40 per cent of a new play area's capital budget. "Do children take greater risks? Do they perceive they're safer than they actually are? Soft surfaces only protect heads. You'll still break an arm."

Rudi Warren, nine, is living proof that the odd accident isn't all bad news. A fall in a north London playground – he copied a friend jumping from a slide to a rope but missed and fell – ended in a broken wrist. He's now more circumspect than his mother, Rachel, who is relaxed about what happened. "I wouldn't do it again," Rudi says. "I've been much more cautious that I shouldn't do whatever someone tells me to and should think about what I'm doing."

Something parents might find surprising – I know I did – are the guidelines in favour of a degree of risk set out by the Play Safety Forum, a grouping of national agencies, in a document called "Managing Risk in Play Provision". "Simply reflecting the concerns of the most anxious parents, and altering playground design in an attempt to remove as much risk and challenge as possible, prevents providers from offering important benefits to the vast majority of children and young people," is one choice line. That said, decisions rest with the ones paying the bills, usually local authorities. "Playground companies are definitely innovating a lot more but the problem is you have a risk-averse client base. So it's catch-22," sighs Michael Hoenigmann, API's chairman. Coupled with current austerity drives, which are slicing maintenance budgets, "there's a move to less adventurous, more static equipment. But children don't like that so it's a waste of money in the long term."

The person banging the risk drum loudest is perhaps the least expected: Health and Safety Executive chair Judith Hackitt. "The perception people have is that there's more risk than there really is. Over-protective parents have lost sight of the fact that part of their role is to teach children to be independent. The downside is children are growing up risk unaware. They think they're fireproof." She is far from alone in blaming 24-hour media for blowing up isolated incidents into something parents – wrongly – imagine to be the norm when the reality is there are no more children falling out of trees and no more children being abducted today than a generation or two ago.

The one thing there is more of is traffic. In 2012, Government data shows that 2,272 children were seriously injured, of whom 61 died. This, then, is why kids aren't allowed outside unsupervised. Just 2 per cent of children cycle to school, for example, according to research, although nearly half of children say they'd like to. It also helps explain why the proportion being driven rose to 44 per cent in 2012, up from 38 per cent in 1995. Parent-led initiatives such as Playing Out, which shuts streets to cars for a certain period each week, are helping, but the bureaucracy involved is massive and progress is slow.

What, then, can we do? For Professor Gray it's all about challenging those boundaries. "Ask, 'Where can I allow my kid more freedom?' and push against the limits of what culture seems to allow.'' And above all, do what you can to get other playmates outside. "Children aren't attracted to the outdoors but to other kids," he points out. Tim Gill, who has spent years working to improve children's lives, thinks it's all about giving your kids "microadventures". He adds: "I hope and believe that growing numbers of parents will sign up to a vision of giving children more everyday freedom. And that those parents will have an impact. Look for ways to scaffold your children's independence."

If this sounds scary, just take it step by step. Gill used to let his daughter choose the stairs on the Underground instead of the escalator; Louis has been taking easy detours on his own ever since he was three, often no more than a few metres. But it all builds up, that tightness in your chest gradually easing. And so I swear I barely blinked this morning when a worried woman called after my departing bike, "Your son. He's gone the other way." Because two minutes later there he was, whizzing into view exactly where I expected him, that smile justifying my boldness.

Bring on the microadventures.

The way we played: Adventures in time

1950s: Peter Popham

I grew up 150 yards from Richmond Park and its hundreds of acres of unpatrolled wilderness, with gates that were never locked, ponds deep enough to drown in and woods and bracken enough to hide any number of homicidal perverts. My sister and I roamed this wonderful area unaccompanied and unchecked from the age of four or five. Growing up in the 1950s [b. 1952] there was awareness of the potential dangers posed by “dirty old men”, and we were warned not to speak to strangers or get into a stranger’s car, but this mild parental paranoia never escalated into direct supervision: I taught myself to swim in Leg of Mutton pond, skated on Pen Ponds when they froze, sledged in Petersham Park when it snowed, built dams across the brook, learnt to ride a bike on the path to Bog Lodge and played for hours in the dense woods of Sheen Common. Sometimes Mum or Dad were on hand, but often they weren’t; back then it simply wasn’t an issue.

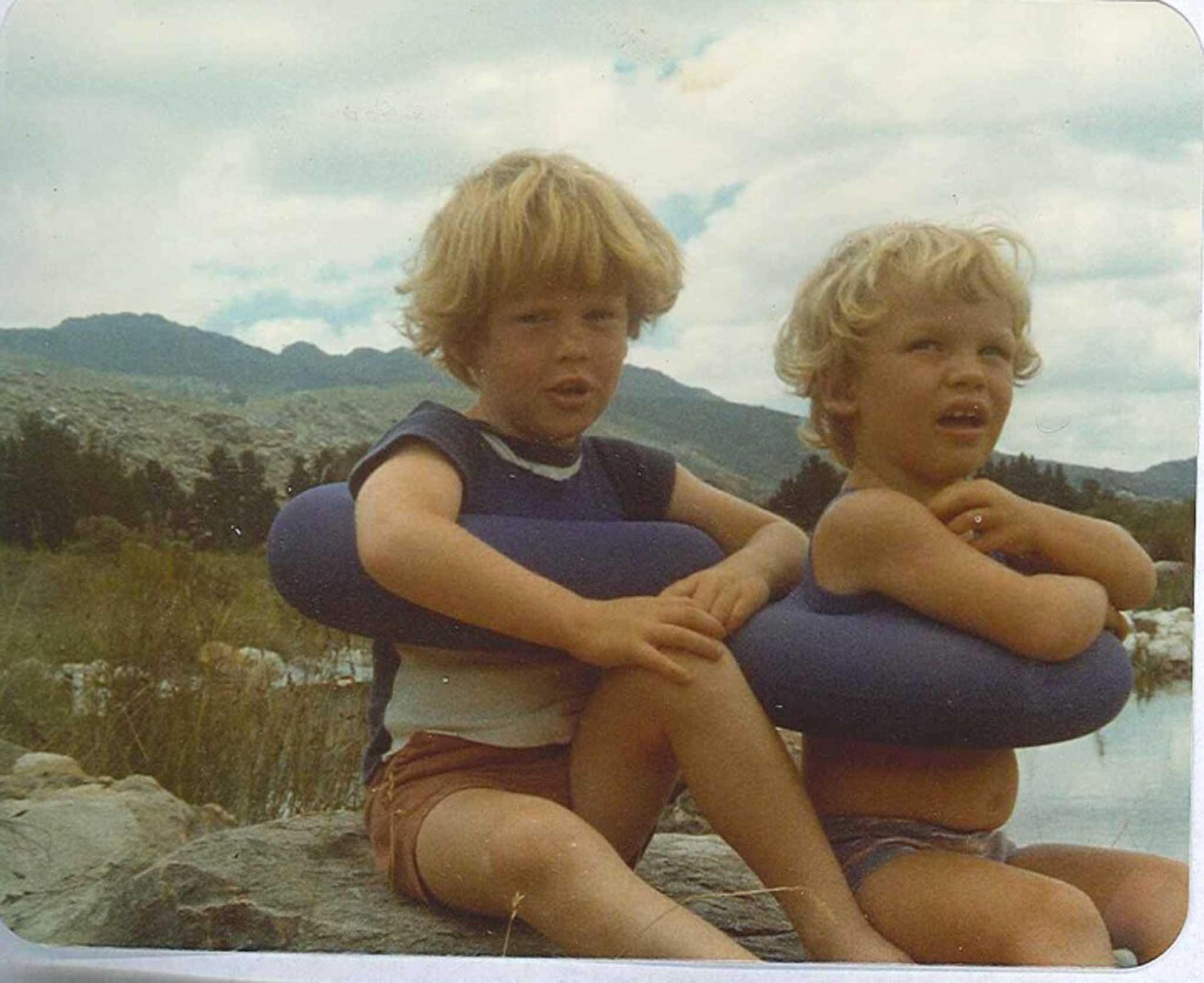

1970s: Mike Higgins

All of the stories about my and my brother’s childhood that my elder daughter likes to hear sound a bit hairy by modern standards. We grew up in Cape Town until the age of seven or eight, and spent a lot of time outdoors. I remember my brother (above right) coming home with a gashed foot after playing on a building site all afternoon. We loved spending as much time as possible up on our suburban bungalow’s roof, picking at bodies of dead lizards and taunting our mother. And we often went barefoot, the soles of our small feet growing thick on the hot pavements. The only place I recall being completely out of bounds was a big concrete drainage ditch round the corner. A few times, Gavin escaped good and proper, and was found a few miles away wandering about or on my bike. And I did once swing as high as I could at the local playground before throwing myself off to see what would happen. I landed on my head, and it hurt, a lot (no bouncy floors back then).

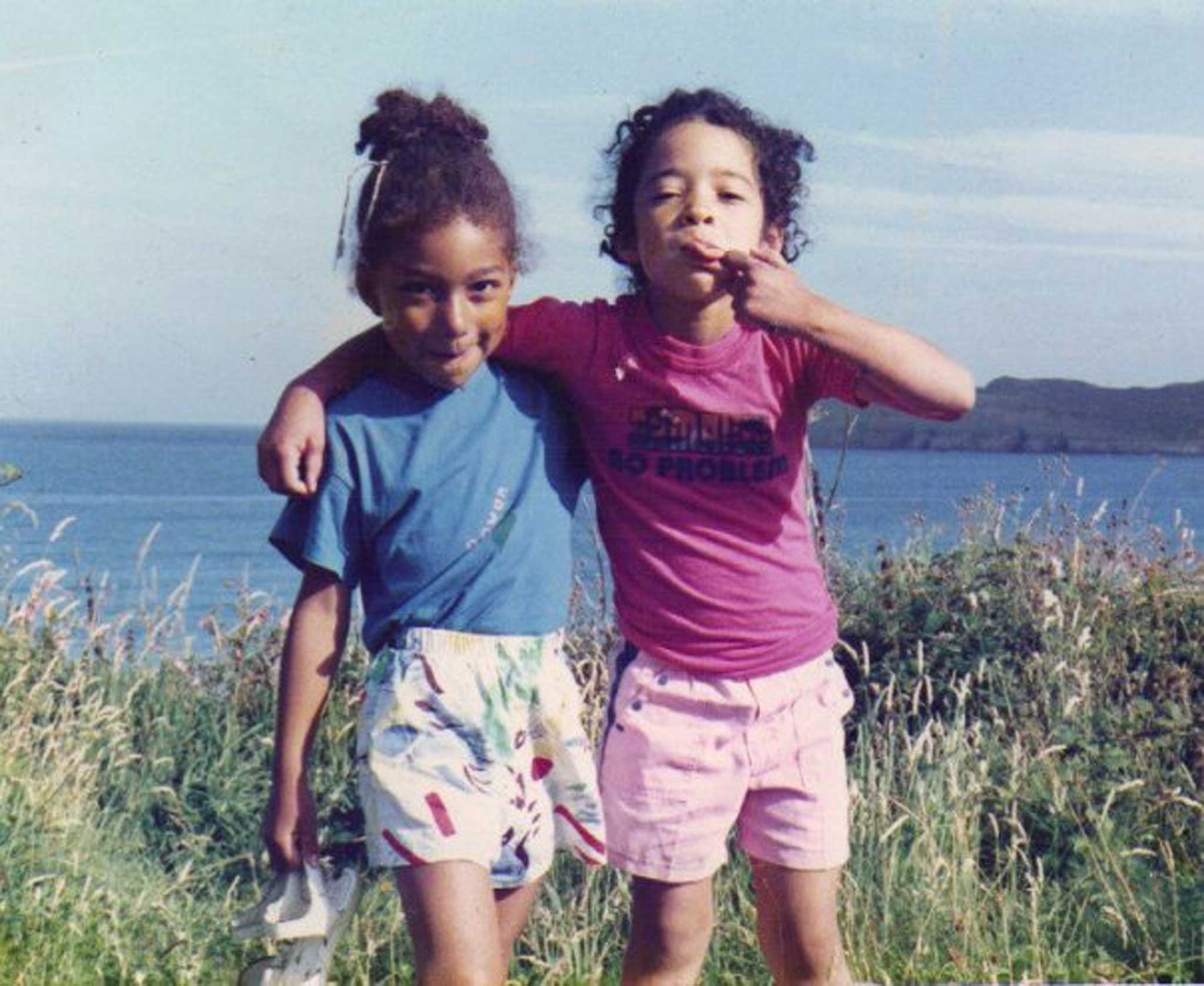

1990s: Ellen E Jones

I grew up on a council estate in the east London borough of Hackney, before the posh people stole it and turned it into an urban-themed play area for their offspring (you know who you are). We didn’t have a garden, but there was a small tyre swing and a death-trap climbing frame which my mum could see from our 5th-floor balcony. I was allowed to “play out” there from the age of seven. When I was about nine, my realm expanded to include the shops round the corner. That was it. I never learnt to ride a bike (no space) and there weren’t any fields to roam in (that’s me on holiday, above right), but what my upbringing lacked in flora variety, it made up in fauna. The nature of inner-city housing meant more people in closer quarters boasting all manner of ethnicities and mental-health diagnoses. I had met a greater swathe of humanity by my thirteenth birthday than most meet by their thirtieth. It was an idyllic childhood – though probably not as Enid Blyton would have imagined it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks