Brexit: Access to potentially life-saving clinical trials ‘at risk’ for 600,000 patients

Exclusive: ‘There is a real risk patients will miss out’ due to new EU regulations

More than 600,000 patients a year could be denied access to potentially life-saving clinical trials after Brexit, medical research organisations have warned.

New regulations are set to make it significantly easier for drug companies to test pioneering new treatments in EU countries – sparking concerns the UK will be “bypassed altogether” when it leaves the bloc.

Many patients, including those with cancer, diabetes and rare diseases, benefit greatly from access to drugs in late stages of testing that are not yet available on the NHS.

But Beth Thompson, senior policy adviser at the Wellcome Trust, which funds medical research, told The Independent: “There is a real risk that patients will miss out” when the new EU rules come into operation late next year.

“It’s going to become more complicated to run a trial here, with our population of around 60 million, than it is to go to the whole of the EU, which has a population of 500 million,” she said. “There’s a risk that people might bypass the UK altogether and just go to Europe.”

The new regulations, which the UK helped to draw up, aim to streamline the application process for clinical trials through a single approval system for all 28 countries.

They will replace the current system, which has been criticised as slow and bureaucratic and requires separate and often very different applications for each member state.

“The risk is definitely there that when the UK leaves the EU, and with it leaves that harmonised framework, that it will reduce the number of trials that happen in the UK,” said Ms Thompson.

“We don’t know yet what the UK’s future relationship with the EU will look like in terms of these trials. We’d really like to see the UK seeking to harmonise with the clinical trials regulation and seeking access to the IT infrastructure that underpins it.”

The fears about drugs trials follow warnings that the introduction of new licenced medicines in the UK could also be delayed after Brexit, with cancer drugs likely to be particularly badly affected.

The UK is expected to leave the European Medicines Agency, which regulates medicines within the EU, Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt has said, leading to concerns Britain could join the “back of the queue” after Japan, the US and the EU when new drugs are introduced.

Clinical trials can be “vital” for patients with rare diseases, said Aisling Burnand, head of the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC). “By the nature of rare diseases, no single country will have enough people with a particular condition to undertake clinical trials of significance,” she said.

“Involving the larger EU population not only means that clinical trials can take place, but the EU’s regulatory process also makes it cost-effective to bring innovative new therapies to rare disease patients.”

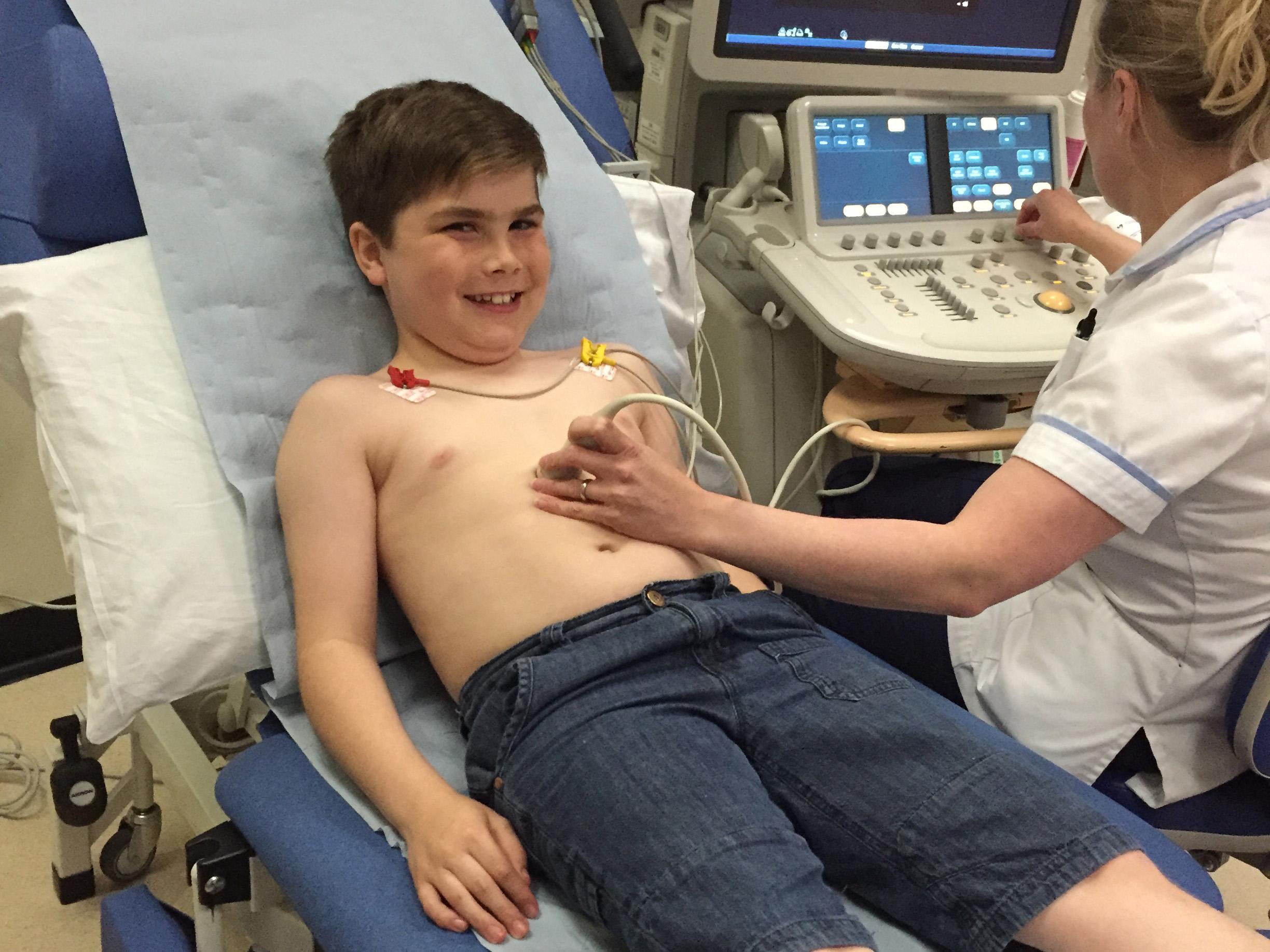

The mother of a 10-year-old boy with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a life-limiting condition that affects around 2,500 children in the UK, mainly boys, said her son taking part in a clinical trial had given her “a huge amount of hope”.

“Boys with Duchenne usually only get seen by a consultant every six to eight months,” said Emma Hallam. She has been told this is because of the degenerative nature of the condition.

“They say, ‘It’s never going to get better, so there’s no point reviewing him more often, because there’s never going to good news, it’s only going to be bad.’ That’s not something you want to hear about your child.”

But taking part in a clinical trial means her son Alex travels to Newcastle every month, where “he’s seen by top-notch people who understand Duchenne and see a lot of boys, so I know Alex is getting the best care possible".

Ms Hallam, who has set up a charity called Alex’s Wish to raise money for research into the disease, said Alex was the third boy in the world to try the new drug, and the first in the UK.

If the drug is proven to be effective, he will be able to keep taking it while it goes through the often-lengthy approval process.

A reduction in the number of clinical trials available to UK patients would be “disastrous” and a “huge, massive disappointment” for boys like Alex, said Ms Hallam. “People will move abroad to access clinical trials, because when you’ve got a child with a condition like Duchenne, you’ll do anything for them.”

But the prospect of tough negotiations ahead means huge uncertainty remains about what leaving the EU will mean for the drugs industry and clinical trials – which could be detrimental to current research, said Alastair Kent, head of Genetic Alliance UK.

“If there is uncertainty about the future trial regime post-Brexit, then companies who have a choice will potentially hedge their bets,” he said. “There’s an important need for government to make clear its intentions on how it sees these proceedings."

“It’s not just what Government wants, it’s what the rest of Europe wants,” added Mr Kent. “Certainly some of the messages coming out of the other member states are: ‘Britain can’t be seen to be better off leaving, as it will encourage the others’.

“Whereas we might want to maintain a harmonised regime and still be able to play, if the rest of Europe says you can’t, we’re forced into a disadvantageous position.”

A spokesperson for the JDRF, which funds research into new treatments for type 1 diabetes, also said current uncertainty could cause problems because the timelines involved in planning research can be so long.

Paul Workman, head of the Institute of Cancer Research, said: “Any regulatory barriers to working collaboratively with colleagues in the EU would limit our opportunities to take part in and lead these trials, which would have an impact on both research and patients.

“The outcome of the Brexit negotiations must ensure the UK remains competitive in a very tough environment.”

There were more than 605,000 participants in clinical research studies in 2015-16, according to the National Institute for Health Research.

A Department of Health spokesperson said it was “determined NHS patients continue to access the most cutting-edge drugs and treatment”, adding: “Innovation will form part of our negotiations as we look to secure the best deal for Britain.”

Ian Hudson, head of UK medical regulatory body the MHRA, said that “as part of exit negotiations we will discuss with the European Union and Member States how best to continue cooperation in the field of clinical trials”.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments